I have been an unpaid carer, and as a coach, I knew that in my darkest times what I really needed to support me in my caring role was someone who could offer a supportive space and challenge to my thinking: in other words, another coach. When I was no longer caring, in 2011, I offered to set up a pilot coaching programme at my local carers’ centre in a voluntary capacity. My work there over the past seven years has been fascinating and enlightening, and has deepened my resolve to champion and support this work at a national level.

When speaking at BACP’s Working with Coaching day in January 2018, I asked the audience how many of them had ever been, or knew someone who is currently, an unpaid carer. The number of hands that went up in response did not surprise me. Many of us are familiar with the role, but I wonder how many of you consider unpaid carers as a potential client group for coaching?

Who are we talking about?

There is no ‘typical’ carer. According to Carers Trust, a carer is anyone who cares, unpaid, for a friend or family member who, due to illness, disability or addiction, cannot cope without their support.1 This could be sons and daughters caring for parents (or grandparents), husbands/wives/partners caring for each other, parents caring for disabled children, or children and young people caring for ill or disabled parents, with siblings, friends and neighbours helping out. In my coaching work over the past seven years, I have encountered all of these.

Life as an unpaid carer: would you apply for this job?

So – just to be clear – this is a job which, while it is primarily about taking care of someone, involves carrying out multiple roles and juggling conflicting demands on both time and energy. Unlike parenthood, it is not a role that people generally choose; it is mostly thrust upon them. Children generally grow up and become independent. The cared-for person in most cases will only deteriorate and become more dependent. Some parents of disabled children never see their child reach independence. Some people may be ‘sandwich carers’, ie bringing up children at the same time as caring for an older adult.

The daily reality for many carers is relentless, exhausting and often unpleasant or demeaning, with little or no support, reward or recognition. Being on duty up to 24 hours a day, and dealing with unpredictable changes, with little time to reflect, plan or take stock, means that, for many, they struggle to attend to their own needs – or even live their own lives. It is common for carers to experience burnout, stress, exhaustion, loss of confidence and self-esteem. It can leave people feeling confused, isolated, uncertain of the right thing to do – and largely invisible. It evokes a vast range of physical, mental and emotional responses.

Hugh Marriott, writing about the ‘emotional whirlpool’ of caring, sums up the conflict that many carers face: ‘Considering how many sound reasons there are for being a carer, anyone would think that we’d feel really good about ourselves for doing this valuable and worthwhile job. Yet the fact is that most of us experience periods when we despise ourselves for doing it, hate [the person we care for] for being the cause of our troubles and yearn for escape.’2

Why should we pay attention to this?

- We all need unpaid carers to carry on caring because, without their input, the NHS and social care would collapse. Carers UK estimates that the support provided by the UK’s unpaid carers is worth an estimated £132 billion per year – more than the NHS’s annual budget in England.3 Cuts to services therefore increase the pressure on unpaid carers, impacting their quality of life.

- Many unpaid carers are also employees – and they are a growing, but largely invisible, section of the workforce, which cannot be ignored. Currently one in nine of the UK’s workforce is caring for someone who is older, disabled or seriously ill, with the number of carers in the UK set to rise from six million to nine million over the next 30 years.4

- Every year, over two million people become carers, so if you are not already, you could very well become a carer yourself in the future – current trends indicate that three out of five of us will become carers at some point in our lives – or it may be you on the receiving end of care.5

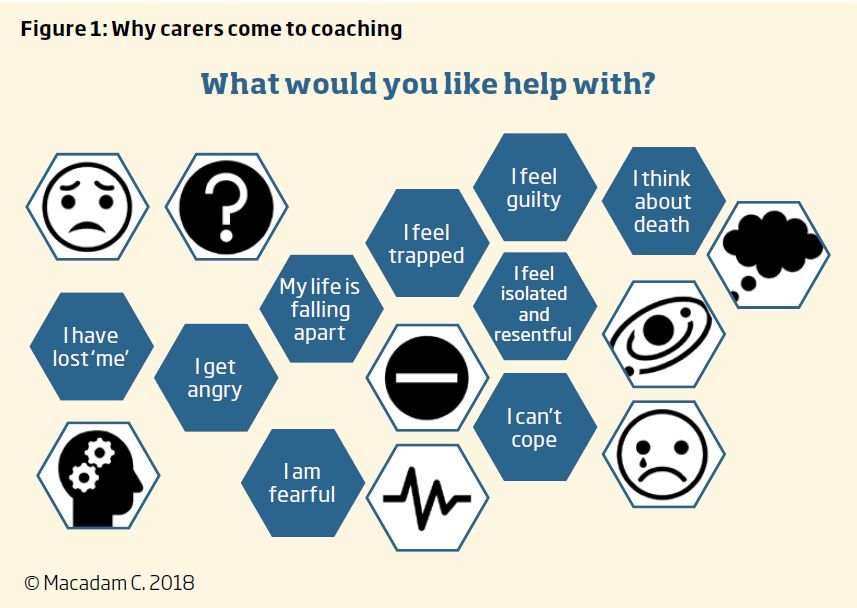

Why do carers come to coaching?

Most unpaid carers come for help – any form of help – and a chance to talk to someone. Some of them may have had counselling before being referred; some come precisely because they don’t want counselling, and are drawn to the idea of coaching being about ‘practical things’ and making progress. But, however ‘practical’ the issues they present with might appear on the surface (jobs, fitness regimes, driving tests, paperwork), often what they really want help with is what lies behind the presenting issue.

Many of the carers I have worked with would not pass my usual criteria of ‘readiness for coaching’ or fit the non-clinical profile of my other coaching clients. They may present as hopeless or helpless, while others may present as supremely confident, minimising or discounting their underlying problems. But despite their vulnerability, the fact that they are in the room with me is a sign of their resourcefulness, doggedness and determination to ‘get through’ whatever life (and other people) are throwing at them.

How can we coaches work with this?

We can, and we should. As I outlined in an article in 2012,6 there are many ways to work successfully with this client group as a coach, to provide empathy and compassion, reinforcement, structure – and hope. To do this work well, we need to be prepared to work on emotional and psychological blockages, but as a coach, rather than a counsellor, using psychological coaching/coaching psychology approaches, such as those set out in Palmer and Whybrow (2008)7 and Passmore (2014).8

To work safely and ethically with such a potentially vulnerable group, it is particularly important to establish and maintain boundaries, develop support networks with other coaches (or counsellors) who are working with these clients, undertake supervision with someone who understands this way of working, and be informed about other support available so that you can make onward referrals if necessary.

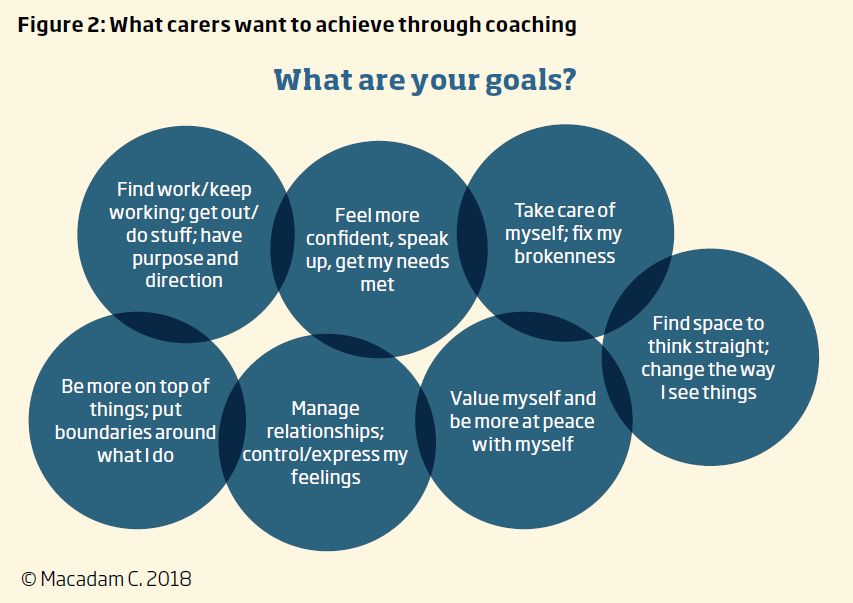

Goals: how helpful are they?

As coaches, we are trained to work with goals and this can be helpful in giving a focus to our work with clients. But there are also risks associated with goals, particularly with this client group. My work with unpaid carers has given me a different perspective on goals. The sort of goals that carers articulate at the start of coaching may be practical stuff about doing things – or not doing things. But much of it is actually about re-engaging with themselves as people, rather than ‘caring machines’, without which, change will not be possible. What I have learned is:

- It’s important to take time to listen and really understand what a) is possible and b) will have the greatest benefit – and keep checking back, because things change constantly;

- It may take longer than expected to articulate a really useful goal. The identification of a goal may well be the outcome of the coaching, rather than the starting point;

- Consider (as David Megginson has9) whether we need goals for coaching to be successful. Would a focus on values, meaning and purpose be more fruitful?

Which tools and techniques are helpful?

Whether you are working towards a clearly articulated goal, or not, there are a range of tools and techniques that I have found work particularly well with this client group:

- Strengths-based, solution-focused or appreciative approaches designed to build confidence, and self-belief and focus on what is going well;

- Cognitive behavioural and positive psychology approaches – to help tackle self-limiting beliefs or negative thinking and deal with painful emotions and relationships (often with the person they are caring for);

- Compassion-focused approaches to foster feelings of self-worth, address the internal critical voice and counteract the guilt that is so often associated with wanting something different for themselves.

Is this coaching or counselling or both or neither?

On my journey from coaching to psychological coaching, through my work with my supervisor, I was introduced to the personal consultancy model as a way of working effectively with this client group. It offers a framework that integrates counselling and coaching, and recognises that although it may be possible to separate the activities of counselling and coaching, it is not possible to separate the client, and that people generally want to explore their emotional depths as well as make practical changes, calling for a focus on both restorative and proactive work.10

The model focuses on the three dimensions of client, practitioner and relationship and four (non-linear) stages of authentic listening, rebalancing, generating and supporting. I have found this to be a great learning tool that has generated self-reflection and developmental discussions in the context of my supervision, and I have used the framework to reflect on my work with unpaid carers, using a reflection log based on the personal consultancy model.11 By tracking the coaching conversation with my client, noting what comes up and where we spend our time, I can capture and understand what they need from me, see how well I am responding to those needs, reflect on the work we have done together, and identify potential areas of future focus.

With my carer clients, I am learning to spend more time ‘being with’ them and worrying less if I am not ‘doing with’ them, using this time to help them understand their existing patterns and the challenges involved in changing them. As the relationship develops, it has been interesting to note the progression from focus on surface issues (stories, problems or conflicts, aims and goals and practical changes) to deeper issues, such as how they have experienced what has happened to them and the person they care for, the beliefs, values, attitudes and needs that underpin their choices, what the experience of change will mean for them and what help I can provide to sustain them through this. This led me to extend my coaching offer from six to nine sessions (with an additional follow-up after a few months), in recognition of the time it can take to move on from talking about surface issues and existing patterns to the deeper, more transformational work required to uncover potential new patterns and the beliefs, courage and skills needed to manifest these.

How might coaching unpaid carers add value to your work?

There is a growing awareness among employers of the impact that unpaid caring has on work and careers. The negative effects of caring include tiredness, lateness and stress, taking a lower status or less demanding role, or turning down promotion.15 For many people, the strain of juggling work and caring responsibilities impacts their performance, health and often earning potential – for some, it is just too much. According to David Grayson, author of Take Care: How to be a Great Employer for Carers, without the necessary empathy, information, flexibility and support, far too many carers are leaving the workplace.16

But awareness is also growing of the business benefits of employing or retaining unpaid carers in the workforce. Ian Peters, Chair of Employers for Carers, says that this is not corporate philanthropy: ‘policies and practices that support carers are … crucial to the resilience and success of your business’.17 But according to People Management magazine, in 2015 only 38 per cent of employers monitored the caring responsibilities of their workforce.18 Without awareness of the needs of workforce carers, employers cannot offer appropriate support.

Why coaching?

Most workplace carers are ‘hiding in plain sight’, unable to talk to managers or colleagues about their caring responsibilities.19 Coaching is a great way to support working carers, because it can be tailored to the individual, it is flexible, it provides a safe place to explore difficult/emotional issues to do with work, and it is known to work well with people who are stressed, overwhelmed and who are not reaching their full potential. I have seen the evidence.

Call to action: how you can contribute

With many carers opting to reduce their working hours, take lower-paid work, or give up work altogether, many end up in financial hardship, perhaps dependent on benefits, or on those they are caring for, who are themselves on a fixed income. This means that many carers end up cutting back on activities that are fundamental to their wellbeing, or on paid support services that help them with caring.20 Paying for coaching in this context is not a viable option. Carers rely on whatever support they can access via their local carers’ centre, under the umbrella of the Carers Trust. But even these charities struggle to keep services going, relying on funding from hard-pressed local authorities, piecemeal grant funding and the generosity of volunteers.

What you can do:

- Think about the organisations you work for – find out if they have policies for supporting carers, start a conversation with them and target your offer accordingly (see box for sources of information to build a business case).

- If you have personal experience of caring, so much the better – make the most of the understanding you bring to this work.

- If you don’t, but would like to learn more, reach out to your local carers’ centre, and gain valuable experience by offering some pro-bono coaching sessions.

- Think about collaborating with like-minded practitioners to work out how you can contribute to providing coaching for people who so desperately need it but can rarely afford it.

- Contact me to join forces. I have set up a LinkedIn group, Coaching Unpaid Carers, where you can find out more and share your ideas. Connect with me on LinkedIn (see below) to join.

Working with the Jo Cox Loneliness Commission, Carers UK urges us all to think about the part we can play in bringing about a cultural shift towards a society that recognises and understands the issues surrounding caring, ageing and disability.21 Caring is part and parcel of everyday life – more people talking openly about caring responsibilities would reflect this and facilitate deeper understanding of the specific challenges faced by those who care for others. I have seen the transformative effects of coaching on the lives of unpaid carers who are so often ignored or overlooked. As coaches, I believe we have a valuable contribution to make – if we care enough to do it.

The case studies are fictional composites that contain factors and quotes drawn from more than one client with similar presenting issues.

Catherine Macadam is a coach, mentor and organisational development consultant working mainly in the public and third sectors. A lay board member for the NHS and a former carer, she believes passionately that more needs to be done for unpaid carers. Catherine has qualifications in psychological and health and wellbeing coaching, and coaching supervision and she is interested in exploring a more integrative approach to coaching and counselling.

To join the conversation about coaching unpaid carers, contact her at:

catherine@cmacadam.co.uk

www.cmacadam.co.uk

www.linkedin.com/in/catherine-macadam-43905914

References

1 Carers Trust. About carers. [Online.] https://carers. org/what-carer

2 Marriott H. The selfish pig’s guide to caring. London: Sphere; 2003.

3 Carers UK. State of Caring report 2018. [Online.] www.carersuk.org/images/Downloads/SoC2018/ State-of-Caring-report-2018.pdf

4 Employers for carers. Business case. [Online.] www.employersforcarers.org/business-case

5 Employers for carers. Facts and figures. [Online.] www.employersforcarers.org/resources/facts-andfigures

6 Macadam C. Intensive care. Coaching at Work 2012; 7(4): 42–44. [Online.] www.cmacadam.co.uk/ downloads/CoachingforCarers.pdf

7 Palmer S, Whybrow A (eds). Handbook of coaching psychology. Hove: Routledge; 2008.

8 Passmore J (ed). Mastery in coaching. London: Kogan Page; 2014.

9 Megginson D. Beyond goals: reflections on writing about goals. The OCM Coach and Mentor Journal 2014: 20–22.

10 Popovic N, Jinks D. Personal consultancy: a model for integrating counselling and coaching. Hove: Routledge; 2014.

11 Popovic N, Jinks D. Personal consultancy, a model for integrating counselling and coaching. Hove: Routledge; 2014: Chapter 6; 67–78.

12 Karpman S. Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin 1968; 7(26): 39–43.

13 Psychology tools. Behavioral experiment. [Online.] www.psychologytools.com/worksheet/behavioralexperiment/

14 Covey S R. The 7 habits of highly effective people. London: Simon and Schuster; 1999.

15 Carers UK. Juggling work and care. [Online.] www. carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library/ state-of-caring-report-2017

16 Grayson D. Take care: how to be a great employer for working carers. Bingley: Emerald; 2017.

17 Employers for carers. Welcome from our Chair. [Online.] www.employersforcarers.org/about-us/ welcome-from-chair

18 Lewis G. It’s emotional being a carer and an employee at the same time. People Management 2015; July: 36–37.

19 Makoff A. Most workplace carers ‘hiding in plain sight’. [Online.] People Management 2017. www. peoplemanagement.co.uk/news/articles/most-workplace-carers-hiding-plain-sight

20 Carers UK. Costs of caring. [Online.] www.carersuk. org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library/ state-of-caring-report-2017.

21 Carers UK and Jo Cox Loneliness Commission. The world shrinks: carer loneliness. Jo Cox loneliness research report. [Online.] www.carersuk.org/images/ News__campaigns/The_world_Shrinks_Final.pdf

22 My family care. [Online.] www.myfamilycare.co.uk