Despite the Government and media hype, the numbers of Syrian refugees who will be coming to the UK under the vulnerable persons relocation scheme are relatively small. At the most recent count (September 2015), 216 Syrian people have already been resettled in the UK under the scheme, which was launched in January 2014. It is aimed specifically at the most vulnerable refugees in the UNHCR camps in Jordan and Lebanon – orphan and disabled children, older people, people with disabilities and victims of sexual violence and torture.

From September the Government has committed the UK to accept a quota of 20,000 Syrian refugees, spread over the next five years. But there will be no ‘wave of refugees’ arriving at Heathrow. Indeed, some 4,000 Syrian people have already been granted asylum here since the conflict began, and asylum-seekers from the region, and from other war-torn countries worldwide, continue to be resettled here under other Government schemes.

The Syrian refugees selected through the scheme will have Humanitarian Protection status, however, which means that, unlike asylum-seekers coming to the UK, they will for five years be able to work and claim welfare benefits and will have access to public funds and services. After that, they will presumably have to follow the usual route for all refugees and apply for indefinite leave to remain.

UNHCR recently published a briefing on Culture, Context and the Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing of Syrians, which offers guidance to mental health and psychosocial support staff working with Syrians affected by the conflict, both in the refugee camps and in host countries outside the region (see www.unhcr.org/55f6b90f9.pdf).

The review details the scale of the refugee crisis, its impact on the mental health and wellbeing of the families caught up in it, and the array of emotional, cognitive, physical, and behavioural and social needs that they are likely to have, symptomatic of their exposure to extreme psychological and social distress. But, it says, mental health professionals should not rush to diagnose mental illness; the primary cause is most likely to be the conditions these refugees are encountering daily in their struggles to survive. Non-clinical interventions such as better living conditions could do more to improve their mental health than any psychological or psychiatric intervention. It underlines the importance of treating refugees not as vulnerable victims but as ‘active agents in their lives in the face of adversity’; their care and support should be the business of everyone involved in supporting them in their new homes, not just a few medical specialists. ‘Some of the most important factors in producing psychological morbidity in refugees may be alleviated by planned, integrated rehabilitation programmes and attention to social support and family unity,’ it stresses.

Nothing new

So, how well are services placed in the UK to meet these needs? UK voluntary sector organisations working with refugees and asylum-seekers – and, indeed, other refugees and asylum-seekers themselves – are startled by the unprecedented levels of attention the Syrian refugees are receiving from the media, the general public and the Government. They have been living with these challenges for years. Says Sanja Djeric-Kane, Director of Refugee Action Kingston: ‘We’ve already got around 1,800 on our books, so another 50 isn’t going to make that much difference.’ The real problem, she says, is the lack of any coherent national strategy to deliver the structured, organised, practical support that refugees and asylum-seekers need if they are to integrate successfully into UK society. ‘If we had that structure in place, people would be able to find a place in society much better and would not have so many problems with their mental health,’ she argues. ‘We are lucky here in Kingston in that the local authority supports us – although we don’t know what will happen from April next year, when they review their spending budgets.’

And herein lies the nub: the voluntary sector is largely providing the psychosocial support needed by refugees and asylum-seekers in the UK, wherever they come from. The statutory mental health sector, according to many of those working in the field, is not equipped or resourced to provide the long-term, multi-faceted psychosocial support needed, or even appropriate to do so when many refugees and asylum-seekers are understandably deeply fearful of any state service or official. Yet the voluntary sector has experienced massive cuts in recent years, with many organisations now operating at greatly reduced capacity, if they have survived at all. Says Jude Boyles, Manager of Freedom from Torture’s north-west centre, in Manchester: ‘What is worrying is that the mental health sector has been hugely cut. Many voluntary sector therapy services have had to become IAPT compliant in order to survive and so only offer brief therapies. Third sector services may not be able to work with refugees as they are not able to fund interpretation or their staff haven’t had the training to do this specialist work.’

Richard Garland is Manager of Touchstone IAPT in Leeds, one partner in the consortium of NHS and voluntary sector organisations providing the IAPT service across the city. He is very open about the limitations within which he is working when he tries to reach refugees and asylum-seekers. Touchstone IAPT’s remit is to improve access to talking therapies to black and minority ethnic communities, and he has specifically included refugees and asylum-seekers as one of his primary target groups, but it is hard, he admits, to accommodate their needs and circumstances within the IAPT model. ‘IAPT is what it is. We are working within strict parameters,’ he says. ‘It’s CBT-based and works primarily with anxiety and depression. We are very clear about what we offer and what it helps with, and we do what we can to be as flexible as possible in order to engage with these clients. It’s my job to explore the limits of these parameters to fulfil our remit to widen access to all.’

They deliver services from community venues in the parts of the city where there are large BME populations, their team is trained to work with interpreters, and they try to be more flexible about appointments. ‘Some may struggle to attend sessions because they have much more important appointments to do with issues like housing or their asylum status, so we for instance tend to give them more chances than IAPT usually would before we de-activate their cases,’ Richard says. ‘And we have maintained our own direct referral route so we can manage referrals in the way we see as most effective in fulfilling our remit to improve access.’

Touchstone IAPT has managed to access funding for a mental health assessment worker to conduct assessments at the weekly drop-in run by PAFRAS (Positive Action for Refugees and Asylum-Seekers), an advice and advocacy service for refugees and asylum-seekers in Leeds. A key aspect of the role is to refer people on to appropriate therapy services, including IAPT and the step 4 NHS psychological therapy service. But the waiting time for step 4 psychology is up to a year, and it has within it no specialist trauma service. ‘There is no service in Leeds that can hold trauma clients and work to stabilise them while they are waiting for step 4 treatment,’ Richard says. ‘Touchstone IAPT has tried to fill this gap in the past but our hands are ultimately tied by factors such as the number of people IAPT therapists are expected to see every week and our recovery targets.’ He was able in 2012 for six months to allocate one CBT therapist to work with refugees and asylum-seekers but the resulting drop in the therapist’s outcomes figures and anxiety among her NHS clinical supervisors about supervising this work meant he had to end the arrangement.

Voluntary sector services

Solace is one of the voluntary sector organisations in Leeds to which Touchstone IAPT makes referrals. It is the only agency in the Yorkshire and Humber region dedicated to providing psychotherapy, including specialist pain and trauma therapies, with advocacy support, to refugees and asylum-seekers. Originally set up in 2006, in response to a huge influx of refugees to the area through the Government’s National Asylum Support Service dispersal scheme, Solace has had to downsize in the past two years after two large grants from the Big Lottery Fund and Comic Relief came to an end. It continues to rely on trust funds, including the Big Lottery Fund, as it has received very limited funding from the public sector. It has already been asked to provide therapy to Syrian families who are beginning to arrive in the city.

Solace’s paid staff currently comprise two qualified systemic psychotherapists, who are also trauma specialists, and one full-time pain and trauma therapist, who volunteers half his hours. It also has 12 volunteer therapists and has recently taken on two family therapy trainees. In August it had to close its doors to new referrals for two months, in order to manage its waiting list.

Solace also provides training and consultancy for NHS, IAPT and other organisations, and sees this as an increasingly important element of its activity, especially as Syrian refugees are likely to be dispersed to communities with no previous experience of hosting refugees.

That more than half their referrals come from the NHS is not surprising, says Clinical Director Anne Burghgraef: ‘NHS services are not equipped to deal with the complexity of cultural, psychological and social needs that refugees bring.’ She says that what the voluntary sector can uniquely provide is a systemic, multi-modal approach. ‘We start where clients are, rather than making them fit into a particular modality; we tailor a therapy package around their individual situation, initially to stabilise them and then to help them begin to process their experiences.’ Solace offers a wide range of therapies, including systemic family therapy, EMDR, focusing, guided visualisation, bereavement work, stress management and group work. Many clients bring very high levels of stress and bodily pain, and the pain and trauma therapist has proved very helpful for them. The partnership work with other agencies is essential: ‘People who are vulnerable and have had to leave their homes need to form new attachments. They may attach to a therapist in the early stages and we help them to move on to form new networks and new attachments, although it isn’t uncommon to keep a Solace connection for a few years,’ Anne says.

‘We aim to help people build up resilience and their internal resources, while also helping them to develop external, social resources by referring them to other organisations and groups. We signpost and support them to do as much as they can for themselves. For many, their whole world view has been challenged and they may not recognise who they are here. We hope to be a part of their journey to a restored life.’

Counselling – an alien concept

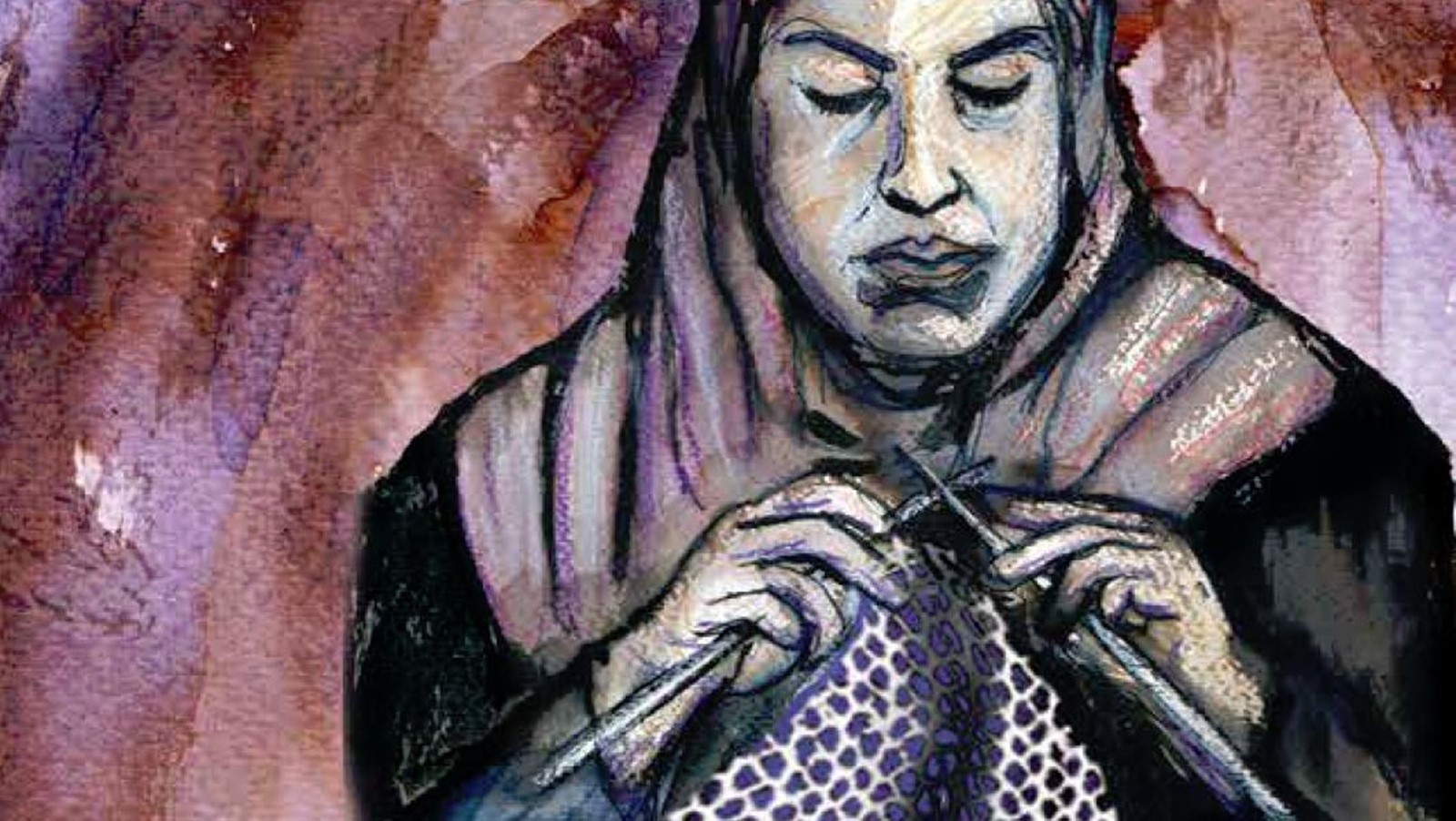

The concept of counselling or therapy is likely to be completely alien to most refugees and asylum-seekers, and especially those from outside Europe, where cultures do not draw a clear separation between mind and body. A lot of pre-therapy work may be needed. Mothertongue, the Reading-based multi-ethnic counselling and listening service, offers informal groups and English classes: ‘We can’t see the point of turning people away because they are not “ready” for counselling,’ says Chief Executive and Clinical Director, Beverley Costa. ‘One of our groups is a knitting group. It provides a place for people – although it has always been women, in fact – to come together with others in a welcoming and lovely space. They can talk and knit, they can knit and not talk, they can talk and not knit. We have even had someone who didn’t knit or talk and still seemed to get something out of it. It’s been really useful in helping people come into the organisation and not feel there is something “mental” about it. It’s also been a way for people to meet other people, to move on from individual therapy and start to form new social networks.’

Another challenge for the NHS is meeting the need for long-term, psychodynamic therapies. The refugees and asylum-seekers most damaged by their experiences are often those who already have a vulnerability relating to their childhood. Dilek Güngör, a migrant herself to the UK from Turkey and now a psychoanalytic psychotherapist, works at the Women’s Therapy Centre in north London and with Nafsiyat, an intercultural therapy centre. ‘At the Women’s Therapy Centre we get a lot of referrals of refugee women from the NHS because the very deep trauma work they need isn’t available. Women come to us because we are a women-only service. They feel safe with us.

‘We work analytically and we can work at depth. We can’t offer more than one year of therapy these days, because of limited resources, although some go on to group therapy after the individual work. To be honest, they all need longer; most of our clients have been tortured or raped or have experienced domestic violence. We are working with very difficult, traumatic experience but in a year we can at least help them understand their problem. We can’t change the past but we can help them see the patterns in their life and develop strong emotional muscles for the future. They use our service well.’

They also get a lot out of the group therapy, she says, although many are initially reluctant to attend. ‘Groupwork works very well for gender-based violence. They find it’s a good way of working because they can identify with one another’s problems and they realise they are not alone.’

Working with young people and children

The Baobab Centre, also in north London, offers long-term psycho-analytically informed psychotherapy to children, adolescents and young adult refugees who have been severely affected by organised violence. Most have come unaccompanied to the UK. All are suffering the effects of overwhelming traumatic experiences and losses, says Sheila Melzak, Baobab’s Clinical Director. ‘Many have seen their parents humiliated, violated, imprisoned or murdered. They will have experienced interpersonal violence themselves. Some have been imprisoned or forcibly recruited to be child soldiers; others have been trafficked for work or sexual purposes.’

Baobab operates as a non-residential therapeutic community, with regular community meetings where all members of the Baobab community, adults and young people, can speak about their experiences in a safe environment and learn that it is possible to express their views openly and disagree without fear of violence. Baobab offers individual and group therapy, discussion groups, and a wide range of group programmes including music workshops, and sports and arts activities. They help the young people access education, health care, benefits and housing, and support them through their asylum claims. Says Sheila: ‘All the research on young people shows they do best if all the services they need are available in one place. We offer holistic, integrated support to address their multiple practical and psychological needs, and we see them for as long as they need. These children have long-term difficulties rooted both in the violence they experienced in their home countries and on their journeys into exile and in the environment in which they are now living, which continually retraumatises them.’ Of the 110 young people receiving their help, just 12 got asylum when they applied, and 69 on appeal, often after many years; the rest are still waiting. ‘They are expected to live with a level of uncertainty about their future that no young person can really cope with,’ Sheila says.

Children have a very different experience of exile to adults, she says. ‘The processes of adjustment are completely different. Very often the children’s lives are significantly normalised by going to school. If they are supported by the school and the school understands the huge transition they are dealing with and has a programme to integrate pupils from different cultures, they adapt much faster than their parents, even if at home they suffer symptoms of trauma and are having to take on adult roles.’

Mentoring in school is very helpful for these children, who may be unable to talk to anyone in their family about their problems because their parents are preoccupied with their own distress. Unaccompanied young people can feel especially lonely, Sheila says. ‘A befriender, who is not a therapist, who can normalise their experience, can play a very useful role. If there were befriending organisations all over the country, staffed by volunteers with support and training, I think that would facilitate integration.’

Volunteering

BACP has been contacted by members in recent weeks asking what counsellors can do, as a profession, to help. Hege Soholt, a child and adolescent psychotherapeutic counsellor based in East Sussex, is one such member who feels BACP could take a lead.

‘I know from those I work with and those I converse with on social media that there are many of us out there wondering what we can do,’ she says. ‘As counsellors and psychotherapists we are in a privileged position to really help but acting alone is not always easy so I contacted BACP as I was wondering what we as a community could do.’

But she also feels that their ethical principles of justice and advocacy challenge counsellors to question the adequacy of the Government’s response to the Syrian crisis. ‘Helping people in need is what we stand for and our ethical principles state that we are there to be advocates for people. With that and the principle of justice, I feel we almost have an obligation to stand up for people who for whatever reasons are not in a position to speak for themselves,’ she says.

The difficulty for voluntary sector organisations delivering support to refugees and asylum-seekers, and often already dependent on volunteer workers, is that they lack the capacity to train and support more volunteers. The levels of trauma presented by clients require specialist skills and supervision. Jude Boyles says Freedom from Torture North West has seen an increase in offers of help from therapists but nationally Freedom from Torture has launched an appeal – its first ever, at www.freedomfromtorture.org/features/8590 – for funds so it can employ, train and provide supervision for additional permanent staff. ‘I think a lot of therapists could adapt their model and transfer their skills very easily to this work but in my experience newly-arrived people need to see someone who is familiar with the range of issues they present. The Syrians we have seen certainly have been subjected to horrific torture.’

If people want to help, Jude suggests they contact the Red Cross or other local refugee organisations that offer more general support. ‘There are many opportunities to volunteer with asylum-seekers and refugees. Do something you can sustain. And if you want to volunteer as therapists, make sure you get training first.’

And there is a huge need for low-level general support within the wider host communities. In Oxford Mina Fazel, a child psychiatrist and research fellow at the university’s Department of Psychiatry, is developing psychological interventions that can be used in schools by any member of staff to support the mental health and wellbeing of refugee and asylum-seeking children. ‘A small number will need specialist treatment for PTSD and that should be provided. But I would say to school counsellors not to underestimate the difference they can make simply by helping these young people settle in school and establish peer groups. A lot can be done at this level to support a whole range of difficulties a young refugee may be experiencing. School is a key venue to embrace these populations in a meaningful way – it’s an important path to inclusion, which is what they want.

‘It’s important not to medicalise their problems,’ she says. ‘We need a multi-tiered approach. Most of the children won’t need the higher level interventions, but they certainly will if we don’t provide the support at this first tier.’

Working with refugees and asylum-seekers

Jude Boyles, Manager of Freedom from Torture’s North West centre in Manchester, talks about trauma work with newly arrived refugees and asylum-seekers

‘The first thing to remember with any newly arrived refugee or asylum-seeker is to pace the information you give them. They are likely to be disorientated, bewildered and traumatised; they won’t always take in all that they are told. So always, in every contact, take time to check their understanding and explain and if necessary repeat it.

‘Their initial priorities will be the basics – where they will live, how to register their children in school, how to register with a GP. They’ll also be desperate to know what has happened to people back home, so they may need to be referred to the Red Cross tracing scheme. Support workers are invaluable at this stage – not necessarily therapists but people who are used to working with interpreters and who can help the family orientate and answer their queries as they settle into a routine. Then you can start to assess what the family and children might need in terms of psychological support.

‘It’s important to be flexible when you’re doing the assessment; be prepared for the process to take longer as the refugee or family is likely to have many questions and concerns. Many will be baffled by therapy; it will seem a very bizarre way of solving their problems. They won’t know how to use the space. So take time to explain what it is and why we know it helps and that you are trained to do this work – you’re not just being kind.

‘At Freedom from Torture North West we use a holistic assessment process that we’ve developed to assess the range of needs of an individual or family; it’s not just a psychological assessment. Make it clear that you want to understand all the things that are worrying them and that you will try to get them help with any of their problems if you can. Often the appointment with the therapist will be their only chance to speak freely through a qualified interpreter so it’s understandable that they may bring to sessions a number of pressing issues that aren’t strictly related to therapy until their situation settles and stabilises. It is important to link up new arrivals with other organisations so that they have a range of options and sources of support.

Stablising and normalising

‘We use Judith Herman’s trauma model: relationship building and stabilisation, processing and then reconnection or integration. The early sessions will focus on normalising the survivor’s responses to their experiences and giving them a framework for understanding their feelings so they become less frightening and overwhelming, and then tools to manage them. Make sure they understand that it may take time for some of these symptoms to stabilise – they will want to feel better quickly so they can regain some control in their lives.

‘Once they have stabilised you can move on to therapeutic work around past experiences, but it is important to remember that not everyone will want to do that. People tend to disclose at their own pace, but you also have to give them permission to do so. Many will not believe you want to know what has happened to them and will feel ashamed and disgusted about what has been done to them or they have seen or been part of. They may not feel able to find the words to describe some of their experiences. Give them time and pace the work.

‘Try to use a normal voice; don’t drop your voice, as therapists often do: survivors may interpret a quiet voice as an indication of fragility or weakness. Try not to show in your face or body language that you are horrified or even that you are concerned, or they may think they are distressing you and that they should stop there. But you also need to be able to balance this by being congruent and validating how shocking and disturbing their experiences are.

‘Always try to explain things through your client’s frame of reference. Ask what would happen in their home country if someone was mentally unwell. There may be rituals around mental health that will help you understand their behaviours and that you can use in the work you are doing together. They may be doing positive things that they would have done at home that you can reinforce or, if they are not helpful, suggest an alternative.

‘Refugees will need time to adjust to the therapeutic relationship and the vulnerability of sitting with you. Ensure they don’t over expose themselves and that the relationship builds gradually and safely. Some may find the intimacy of the therapeutic relationship embarrassing and may be confused by the strength of their feelings towards their therapist. When we have asked refugees about their experiences of other therapy services, we sometimes find that they have not realised that those weekly sessions were the treatment; they assumed they were just having helpful conversations with a kind and supportive person. So always, always take time to talk things through and explain.’