On day one of my counselling certificate course, our tutor surveyed the group of eager students in front of her and gleefully declared, ‘We have a man!’ He took an embarrassed bow, the lone male in a room of 15 women. As the weeks unfolded, he seemed well-suited to the work, with natural empathy and emotional insight. But he didn’t continue to the diploma, and I completed most of my training in an all-female group.

It’s a scenario that’s no doubt familiar. For good or bad, by accident or design, counselling is predominantly a women’s realm, and male practitioners are in the minority. Given that the most high-profile ‘founding fathers’ of talking therapy were men (Freud, Jung, Adler, Rogers, Maslow, Skinner, Beck) – with the exception of Melanie Klein – it begs the question, ‘How did we get here?’ And what are the implications?

Pay and prospects

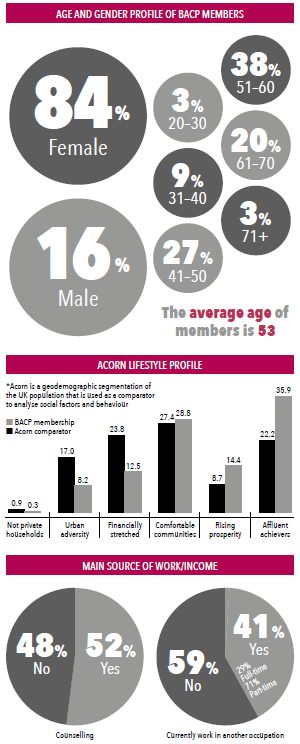

According to a 2014 BACP survey of its membership (BACP represents by far the largest number of counsellors in the UK),1 the gender (im)balance within counselling is 84% female to only 16% male. BACP’s data also tell us that the typical counsellor is aged 53, works 12–13 hours a week, and earns less than £10,000 a year. Yet, in marketing terms, as defined in the survey analysis, she falls into the ‘affluent achiever’ bracket (‘detached house, luxury car, buys wine and books on the internet, has an iPhone’). The disparity between her income and expenditure suggests we can assume she is not the household breadwinner. Just nine per cent of BACP members earn more than £30,000 a year.

There is a similar picture in psychotherapy, says Martin Pollecoff, Chair of the UK Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP). According to the 2016 UKCP member survey, 74% of members are female and 24% male (two per cent preferred not to say); 44% work less than 20 hours a week, and almost half earn less than £20,000 a year from psychotherapy. ‘If you need to earn a living and support a family, why would you get into this job? You can earn more as a bus driver,’ he says.

I am typical of counsellors, it seems. Counselling was a second career for me, and the training involved taking a cut in income, and self-funding the considerable costs (in my case, a total of around £14,000 on courses, therapy, supervision and placement expenses). Recouping that investment through earned income has been a slow process, and my annual earnings are still lower than before I embarked on my first counselling course in 2007.

Moreover, 25% of practising BACP members are unpaid for their main role, and 52% earn less than £10,000. They are also likely to be earning their living by other means, or have several jobs to make ends meet: 48% of members do not rely on counselling as their main source of income; 41% have another occupation, and 48% have two or more roles. The majority – 72% of BACP members – say it is difficult to find employment in the current market.

This may be largely a reflection of the current economic and political climate, but it also perpetuates the gender imbalance. ‘How do you take a counselling course with a full-time job?’ says Sue Wheeler, one of the UK’s first female counselling professors, who recently retired from the role at the University of Leicester. ‘It’s not even a case of take a year off, do some training and then get a job at the end of it. Most routes into counselling involve part-time courses, flexibility and voluntary work, which men may not be prepared to do. Men still expect to be the main breadwinners, which compels them to look for a career that pays.’

More men at the top?

Counselling is also, like many public service professions, and healthcare (as opposed to medical care), a field with a disproportionate number of male clinical leads and service directors. ‘There is evidence in other female-dominated professions like teaching and nursing that men entering the professions rise significantly more quickly through the ranks than women. So it takes them into more traditionally male managerial roles, and I think that is also potentially part of the picture in counselling: that men may come in as coalface counsellors and may end up in management positions,’ says Liz Bondi, a counsellor and Professor of Social Geography at the University of Edinburgh.

But, if men are heading up clinical services, a lot of the key thinking has been done by women, says BACP Chair and counsellor Andrew Reeves. And, Liz Bondi points out, some of the most groundbreaking counselling services were created by women for women, in the 1960s and 1970s: ‘Counselling services that developed through the women’s movement – work around rape, sexual violence against women, the domestic abuse organisations – it was all voluntary action, women supporting women, and it was really pivotal in terms of social change,’ she says.

There is no doubt that female academics, like Sue Wheeler and Liz Bondi, have been pivotal in the development of the profession over the years, says Reeves. ‘But counselling as an activity is not immune from the society and culture in which we are embedded, and we are still a patriarchal society in which men receive advantages over women that are either consciously or unconsciously discriminatory. I think there is something about gender socialisation that continues to place caring, nurturing, empathic attributes more along the feminine spectrum and that men continue to be gender-socialised along the more controlling, managing, stoic, thinking spectrum. Men are more programmed to assert themselves, to articulate themselves and to be taken more seriously.’

Women’s choice

Wheeler believes that part of the explanation for the absence of female clinical leads and service directors is that famous statistic from a Hewlett-Packard report: men will apply for a job even if they meet only 60% of the required qualifications, but women apply only if they meet 100%. ‘In senior roles, there are new challenges, and very few counsellors are trained in management,’ says Wheeler. ‘Women need to think more about management skills and career planning – what skills might it need? I have encouraged women working for me to increase their qualifications and diversify, and those who did have got very good jobs. If you want a career rather than a part-time job, you have to think about what qualifications you need to get there. If you are working purely as a counsellor, you are limited.’

Shift in mindset

Part of the problem, says Dr Sally Aldridge, researcher and former BACP Director and Registrar, is that the behaviour you have to adopt as a counsellor is not necessarily the behaviour you have to adopt as a manager. ‘It is a shift in mindset, which I think not everyone is comfortable with doing. You have to live with a dichotomy in yourself,’ she says. ‘Counselling is non-directive: the client takes responsibility for change. As a manager, you can’t be passive, you have to be comfortable taking the lead.’

Carolyn Couchman, Clinical Director of Bromley Community Counselling Service, says that men tend to use counselling placements more strategically than women. ‘I currently have 56 counsellors in my service, and five are men. In my experience, the men have either taken early retirement to concentrate on a new career, or are younger men in the middle of changing careers, and are using it to get their hours. Once they are qualified, their approach is pragmatic: “I have a mortgage to pay; I need a salary.” The women are more likely to continue in a voluntary role and say, “I just love the work.” A number of them have very successful careers and they volunteer one evening a week to give something back.’

Wheeler agrees that is another part of the explanation: many female counsellors prefer to stay in the therapy room. ‘I have trained 80% women and 20% men in my career and, on the whole, men tend to use counselling training to help them progress in their core profession,’ she says. ‘Women simply love the work and are reluctant to give up being counsellors. It’s not easy giving up what you are most competent at.’

That is certainly true for me: far more important than the money is the personal and professional development and career satisfaction I have gained. Why else would I have knowingly reduced my earning potential as a journalist? In mid-life, I was looking for a vocation and a way to give back to society. Looking at BACP’s membership survey data, it seems I am pretty typical of the profession.

Andrew Reeves begs to differ (only slightly). ‘I think it’s true that women enjoy the work, but men who come into the work enjoy it as well. The difference may be that they are given more opportunities to move out of the role of counsellor,’ he argues. ‘Women may feel they stay in the role of counsellor through choice, but I am not always sure the same opportunities are available to them as they are to men. If they were, they might make different choices. Men are generally brought up to believe that they have a right to achieve their potential and a right to take opportunities. That message is less present in what comes through to women.’

And women may love the work, but is it unreasonable also to expect to earn a living from it? The statistics suggest that, however committed we are, working unpaid is taking its toll. In the BACP survey, only 37% of counsellors who were working unpaid said they were satisfied with their professional life, compared with 75% of those earning more than £30,000 a year. Fifty-three per cent said they were likely to look for other employment in the future, and 58% said there were ‘no opportunities’ open to them for paid employment in counselling.

Nor should we rush to assume that there are more female counsellors because women are better at it than men, says Bondi. ‘In terms of listening, being empathic, doing relational work, all of those things, work that is culturally constructed as more feminine than masculine, counselling will tend to be an easier fit for women than for men. And it may well be that women are more drawn to it because of that and it may be perceived as “women’s work” – work women may do better and enjoy more than men.

‘But, if the question “Is it women’s work?” is coming from the evidence of the majority of counsellors being women, I would want to ask, “Which women?” As well as gender, there are other important differences. If you drill down and follow the logic, are we saying it is “white, middle-aged, middle-class women’s work”, which begins to sound a bit silly, or a bit troubling? We need to think beyond gender and about diversity in general. If we had 50% men and 50% women, but they were mainly white and middle-class, what would we have gained? We need our counsellors to represent the client group.’

More ‘professional’?

So, what needs to change? It’s about taking ourselves seriously as a profession and upping our game in terms of professional status and qualifications, believes Reeves. ‘We might like to compare ourselves with professional groups like the medical profession, teaching and social work, but our entry to the profession is all over the place. We can’t even talk to stakeholders about the minimum qualifications and skillset that employers can expect from a counsellor.’

For Wheeler, it starts with training: she wants to see more degree-level courses. ‘It’s not helping the profession that university courses are closing down and independent courses are dominating – there is no consistency of training,’ she says. Our nearest equivalent, counselling psychologists, are all degree-qualified and, like counsellors, typically do an unpaid placement to get their 450 clinical hours. ‘We recently calculated that they save the NHS around £1.8 million a year,’ says Dr Maureen McIntosh, Chair of the Counselling Psychology division of the British Psychological Society. ‘But it pays off as they can go into the NHS on the same level as a clinical psychologist, on a starting salary between £26,302 and £36,225.’ Compare that with the data from the BACP 2014 survey, where the average annual income of members was £11,700, with over half (52%) earning less than £10,000 a year.

Degree-level entry

Aldridge agrees. ‘If it was the norm that, to get into counselling, you had to get a degree, with a placement that is built into the degree, it would reduce the number of people training and lead to more jobs in the field, and potentially address the gender imbalance. In the 1960s and 1970s, most of the training was in universities. Then, in the 1980s, there was a deliberate move to expand into the further education sector, which, on reflection, wasn’t a good decision,’ she believes.

But it’s a complex issue, and, for many women, the flexibility and relative affordability of further education-based and independent training courses are what make it possible to fit training around an existing job and childcare. Today’s would-be counsellors have no guarantee that investing £27,000 and upwards in a university degree will lead to higher earnings or a structured career path.

There is also the simple fact that the intensity of the work itself limits its maximum earning potential – few of us in private practice have the resilience to see clients back to back, five days a week, or would consider that to be ethical and in the best interests of clients.

Women – and men – who are passionate about counselling find a way to make it work in whatever way they can, and clearly that is often by diversifying – supplementing their incomes with other part-time jobs. For many, possibly those for whom it is a second career, the financial rewards are enough; it’s also readily admitted that many people go into counselling training, at least partly, to ‘find themselves’. And, as Aldridge says, it’s still a win for society at large: ‘Even if they don’t work as counsellors, they still carry those skills and knowledge out into their lives and society.’

Roots of counselling

While psychotherapy is rooted in the male-dominated world of psychoanalysis, women have ‘owned’ counselling from its earliest days, says Sally Aldridge, who is currently researching the history of counselling. ‘There were charitable organisations all over Britain offering counselling to the “deserving poor” through the church. They then developed into social workers and were predominantly women, both working- and middle-class. Then there was help offered to the “undeserving poor” through the courts – the pre-probation service, and “court missionaries”. Relationship counselling came out of the National Marriage Guidance Council, which was established in the 1930s, and had both male and female counsellors. By the 1960s, counselling was being offered under a range of names – career guidance, educational guidance, marriage guidance – in a range of settings, but very often by middle-class women, on a voluntary or part-time basis.’ It wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s, when paid jobs began to emerge, that more men became counsellors, says Aldridge: ‘You could be a counsellor and have a good career in a primary-care setting or in education.’

Sally Brown is a counsellor and coach in private practice (therapythatworks.co.uk), a freelance journalist, and Executive Specialist for Communication for BACP Coaching.

More from Therapy Today

Through the gate

Free article: Catherine Jackson visits HMP Styal, where a pioneering counselling service has developed new ways of working with offenders on short-term sentences. Therapy Today, February 2017

Can counselling help people in poverty?

Open article: Catherine Jackson asks how counselling can help people living in poverty and financial stress. Therapy Today, December 2016

FGM – exposing a hidden child abuse

Free article: Catherine Jackson talks to counsellors about their work with survivors of female genital mutilation. Therapy Today, November 2016

References

1. BACP. Members employment research report. Lutterworth: BACP; 2014.