Young people seeking help for emotional difficulties may also have to deal with a variety of interrelated issues. These challenges may include, for example, developing career plans, fostering greater autonomy and independence, building new relationships, and managing pressures from peers and from institutions.1 The challenge for counsellors and psychotherapists, then, is how best to help young people to address together their psychological difficulties, as well as these social and developmental aspects. While counselling for young people has been useful,2 clients have fed back their preference for more proactive and goal-focused approaches.3,4,5

Coaching is one such approach. Though multiple definitions abound, coaching is generally considered a more proactive approach in achieving behaviour change than standard models of counselling.6,7 Coaching seeks to initiate change with a present-future orientation, using interventions that specifically delineate clients’ goals and the ways to reach them, rather than the past and present orientation that is typical of counselling. Coaching aims to ‘build on existing strengths, [is] less likely to be accompanied by high levels of distress, and [is] driven by the client’s desire to develop their potential, and/or understanding of themselves, their beliefs, behaviours and actions’.8 As young people are inclined to orient towards to the future9 when addressing their difficulties, adding aspects of coaching to counselling may provide a better fit with young people’s preferences for managing their difficulties. And therefore, having the same practitioner work with the young person, therapeutically and developmentally, may be beneficial. This does, however, raise the question of boundaries between the two modes of working and how to navigate these.

Pause for reflection Have you identified areas in your practice where you are working across the boundaries of counselling and coaching? To what extent are your efforts to support both the reparative and developmental needs of your clients acknowledged within your current ways of working?

The personal consultancy model

The personal consultancy model6 of coach-therapy integration that we used in our research study is one way of integrating both a proactive, future-focused approach and a reparative and developmental way of working. It integrates a range of skills from both modes of working, in response to where the client is in their process.

Four ‘stages’ are specified in personal consultancy, the wording of which was adapted by Carolyn Mumby7 for greater applicability to work with young people: being heard, the starting point and basis for the other stages; finding your balance, focusing on identifying helpful and unhelpful patterns to determine what the client wants to work towards; moving forward, focusing on the desired future and, finally, supporting, wherein the practitioner offers support that helps enable the client to reach towards their goals.

The relationship with the client is considered along three dimensions, where the practitioner can work across the modes of ‘being’ and ‘doing’ with the client, on areas of depth or on the surface, and with past and existing patterns or new emerging patterns. The model is intended to be non linear, which means practitioners and their clients can move fluidly and dynamically across stages wherever necessary, rather than working in sequence. The stages, however, allow for demarcation of where counselling or coaching can be used successively and distinctively, but in a flexible way that allows the fullness of these approaches to be used. For example, revisiting the being heard stage at points throughout the engagement may help the client process what has happened in other stages and bolster the therapeutic relationship. Additionally, it may be that some clients require only some and not all of the stages as part of a meaningful piece of work.

Personal consultancy thus provides an integrated framework that may be suited to meeting both the reparative and developmental needs of young people. Yet there was no empirical research on either this approach or indeed any integrated counselling-coaching intervention with young people.

The research: establishing an evidence base

Our mixed-methods study10 was designed in two parts to address gaps in research. We investigated the effectiveness of this integrated approach in youth counselling settings, and also young people’s experiences of receiving this intervention.

1 The effectiveness study

This assigned 80 young people between the ages of 13 and 25 years (and an average age of 16), from four Youth Information Advice and Counselling Services (YIACS) centres in England to two groups: (i) an integrated counselling and coaching group, based on the personal consultancy approach, and (ii) a counselling group that was the standard provision of humanistic counselling offered at each centre.

In order to deliver the integrated counselling, 11 counsellors within the YIACS centres attended five days of training (delivered through Youth Access, the advice and counselling network for young people),1 which introduced counsellors to coaching approaches. The training focused on broadening their coaching skills through exploration of a range of frameworks and interventions intended to help young people draw out their strengths, accomplishments and challenges. Emphasis was placed on how to help young people explore their desires for change and the possibilities for this, against any restrictions on autonomy that adolescents may typically face. How to help young people develop such acceptance and coping strategies was also covered. Personal consultancy was then introduced to help practitioners to integrate coaching skills in ways that would serve to complement their counselling practice, such as balancing attention on goals and the actions required to pursue them, with integrative work addressing internal conflicts of the young person.

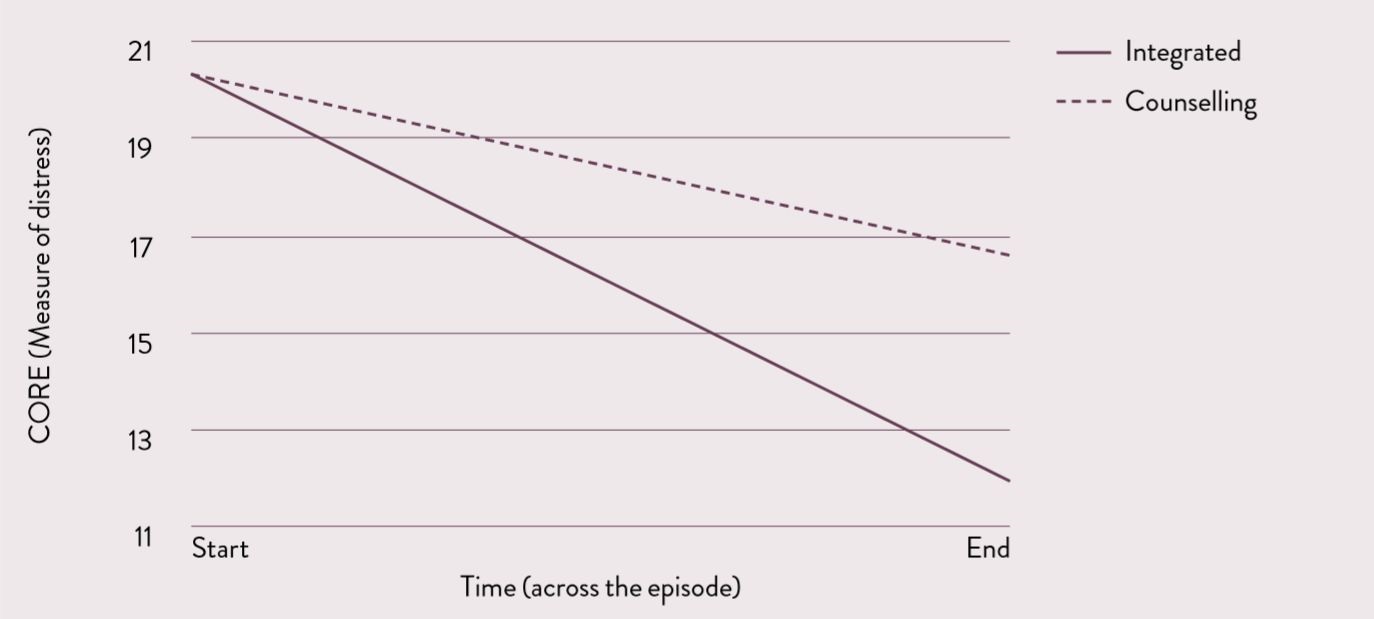

The young people completed CORE self-report measures of distress at the start and end of their counselling episode. Both groups, having begun therapy with moderately severe levels of psychological distress, showed an improvement – moving to moderate levels for the counselling group and mild levels for the integrated group. As hypothesised, we found that the young people in the integrated counselling showed significantly greater reduction in distress than those in the counselling group.

Figure 2: Change in average CORE scores for both groups over time

2 The qualitative study

This part of the research consisted of five semi-structured interviews with young people who had undertaken the integrated counselling. Interview data were analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis. All young people who participated in this research have given informed consent, and their identity has been anonymised.

The five themes that arose for young people were:

- developing a sense of agency – including exercising their own agency, overcoming difficulties, moving forward and making their own decisions, and setting goals, and increase in motivation

- management of their feelings – including being able to manage their emotions better, particularly anger, the venting of built-up feelings in sessions, and their improved mood after sessions

- making sense of the present, past and future – making connections across these time frames, a gained understanding of, and reduced rumination on, the past, and developing a positive outlook on the future

- enhancing interpersonal relationships, which was partly achieved through experiencing different ways of interacting with their personal consultant, and being able to choose positive relationships and manage difficult relationships

- developing self – gaining focus, forming identity, increased openness, changing thought processes and perspective, and building up of confidence.

What did young people say?

These themes tended to reveal the positive experience for young people in addressing both their internal and relational difficulties and their present and future challenges of growing up. The integrated offer seemed to support this through its combining of a reflective and restorative mode, intended to achieve internal change, with a developmental and future-oriented mode, intended to foster external change.

For example, the theme of making sense of past, present and future suggests that a form of practice that can attend to both the past and the future and move comfortably between time frames can be beneficial to young people.

Jade elaborates on this: ‘They all obviously fit together – it’s one continuous time spectrum, and going through what happened in the past affected like how I felt in the present or about my future or about loads of different things kind of combined, and it’s important to like deal with one thing to deal with the next and deal with the now and deal with the future.’

Most participants found that talking about the future, particularly their career plans, helped them form a positive view of the future (which had previously been viewed negatively). Caitlin emphasises this: ‘…we did a future plan; so, what we want from the future and what we can do now to change [things] about the future and help me get to my goals. So I’ve started being good at school, not bunking lessons, working hard, getting along with the teachers and stuff.’ Most participants talked about how they now had a better understanding of their past and as a result are more able to move forward. Caitlin relates this process: ‘And I used to bottle it up and put it in a box and put it away, and now we’ve started to open the boxes and put them where they need to go and forget about them, and so I’m not stressed up about the past and things that could happen and stuff.’

This theme highlights how moving between the time frames of past, present and future – while being flexible on ‘being with the client’ and ‘doing with the client’ in response to their needs – seemed positive for the young people interviewed. An integrated approach allows practitioners to move comfortably between time frames and modes of working.

The future

Our research is the first we know of that provides empirical evidence for the beneficial effects of using an integrated coaching-counselling approach with young people. It also established that young people reported a positive engagement with the intervention and that they experienced constructive cognitive-behavioural and emotional changes. Further research is needed into aspects of the therapist-coach experience. Building an evidence base through further controlled research settings, and evaluation of the experiences of the young people and practitioners who deliver such approaches, are the priority. One research study is currently underway into supervision practices for the therapist-coaches who are working integratively.11

The YIACS integrated health and wellbeing model was an excellent starting point, given its focus on support for various issues within a single, young person-centred setting. Yet we suspect there are many more services and organisations, as well as therapists in private practice, who are in the same predicament of wanting to work in the broader set of ways that help address the range of interrelated needs of their clients. While it may be novel to some, many practitioners are bound to find this type of integration similar to what they already provide, viewing the addition of coaching as something that has a different focus but yet draws on their developed skills in counselling. Either way, it is important that there is a whole discipline that practitioners can access in helping support their often unacknowledged efforts to bridge across boundaries in order to work with young people in the fullest way possible.

Further information

The published research article for this study is available online10 and full access to a limited number of free online copies can be viewed on www.tandfonline.com.

Below is more information about training as a therapist-coach:

- A postgraduate qualification, at diploma and master’s level, in integrative counselling and coaching is available at the University of East London

- If you are interested in training in coaching/personal consultancy, you can contact Carolyn Mumby directly via her website if you are an agency or group of individuals and have eight to 12 participants who would like to train in this approach.

- Alternatively, you can get in touch with Carolyn in her role as chair of BACP Coaching division if you would be interested in being part of a special interest group focused on coaching/personal consultancy for young people: coaching.chair@bacp.co.uk

Alan Flynn is a counselling psychologist in training at the University of East London and associate lecturer with the Open University.

Nicola Sharp is a psychotherapist in private practice. She obtained an MA in counselling and psychotherapy from the University of East London in 2016.

The authors of this study would like to acknowledge and thank all the staff and service users involved, both at Youth Access and at each of the agencies, Off The Record Youth Counselling Croydon, Isle of Wight Youth Trust, Interchange Sheffield Community Interest Company and No Limits (Southampton). Thanks to Carolyn Mumby and Barbara Rayment who made the implementation of this project possible.

References

1 Youth Access. Youth access: an integrated health and wellbeing model. Youth Access; 2015. www.youthaccess. org.uk/downloads/yiacsanintegratedhealthandwellbeingmodel.pdf

2 Cooper M, Pybis J, Hill A et al. Therapeutic outcomes in the Welsh Government’s school-based counselling strategy: an evaluation. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 2013; 13: 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/1473314 5.2012.713372

3 Mumby C. Working at the boundary. Counselling Children and Young People 2011; December: 14–19. www. carolynmumby.com/Mumby_CCYP_ Dec_11.pdf

4 Geldard G, Geldard K. Counselling adolescents: the proactive approach for young people. 3rd edition. London: Sage; 2010.

5 Lynass R, Pykhtina O, Cooper M. A thematic analysis of young people’s experience of counselling in five secondary schools in the UK. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 2012; 12: 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/1473314 5.2011.580853

6 Popovic N, Jinks D. Personal consultancy: a model for integrating counselling and coaching. Hove and New York: Routledge; 2014.

7 Mumby C. Personal consultancy with young people. In: Jinks D, Popovic N. Personal consultancy: a model for integrating counselling and coaching. Hove and New York: Routledge; 2014 (pp139–160).

8 BACP. Position statement 2018: types of intervention: coaching. Unpublished document.

9 Berg I, Steiner T. Children’s solution work. New York: Norton; 2003.

10 Flynn AT, Sharp N, Walsh J, Popovic N. An exploration of an integrated counselling and coaching approach with distressed young people. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 2018; 31(3): 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951 5070.2017.1319800

11 Christmas S. How do personal consultants experience supervision? An interpretative phenomenological analysis [doctoral thesis]. London: University of East London; forthcoming, 2019.