When I trained as a person-centred counsellor in 1999, I discovered something I was passionate about, and that passion remains with me to this day. I started work in a local Christian charity whose ethos of serving society matched my own. I began working with children as well as adults. I had previously owned and led a pre-school for almost 10 years, and so it was natural for me to transition into play therapy as well as working with a wide demographic of adults. It was here that I started to believe in myself.

My manager gave me the freedom to create courses and expand the work of the charity, and facilitated by his acceptance of me, I experienced a flourishing of confidence in my own ability. I became accredited, trained as a supervisor and couples counsellor, and completed specialist training as a trauma counsellor.

My experience of being believed, by both my manager and my training supervisor, was crucial to me in becoming the woman and the practitioner I am today, 20 years later. During these precious years, I set up counselling work in a women’s refuge and it was during this time that my background as a former Page Three model came to light. This was a challenging time for me, as my story became public. I had struggled with heroin addiction 10 years previously, but to see images of my younger self shared on the internet was something else entirely. Some of the clients I worked with at the refuge had experienced issues around pornography addiction and suddenly there were pictures of me online linked to pornography websites. It was an incredibly difficult time for me. Why am I telling you this? I believe that we are the sum of all our parts, and as such, these parts inform our everyday professional and private lives. After working solely as a therapist in private practice for many years, I attended a BACP course on coaching approaches and discovered my next passion: executive coaching. I found myself in the exciting new position of working both as a coach and a therapist. The question for me now was: how will my counselling background inform my coaching work? In my experience, the differences and similarities between counselling and coaching can be fluid, and it is this view that went some way towards the formation of my own integrated model.

One of my favourite writers is Brene Brown. I find her work around shame and vulnerability incredibly inspiring. Her book, Daring Greatly, 1 and her TED talk on shame, guilt and the power of vulnerability,2 highlight issues that many of us deal with.

I often coach people in positions of authority who find the idea of being open and vulnerable excruciatingly painful. I have counted myself among this group at certain times in my life, especially when people find out about my past, but I have been surprised at their ready acceptance of me. The problem with vulnerability, however, is that it nudges our imposter into action:

- If they know that about me, what will they think?

- If I tell them I feel low, will they label me with a mental health issue?

It is vital, I believe, that we are not afraid to work with these issues. I do, however, believe that a coach will not be able to take a client to places where they have not been themselves. All therapists are required to have regular supervision to ensure the best quality of care, and I believe that coaches would also benefit from this provision. In her book, Reflective Practice and Supervision for Coaches, coach and supervisor Julie Hay argues that focusing on our practice in supervision increases our self-awareness and competence.3 It is only as we reflect on our practice that we can shed light on how we may impact the work. Supervision is the place of stretch and development.

Crossing the valley

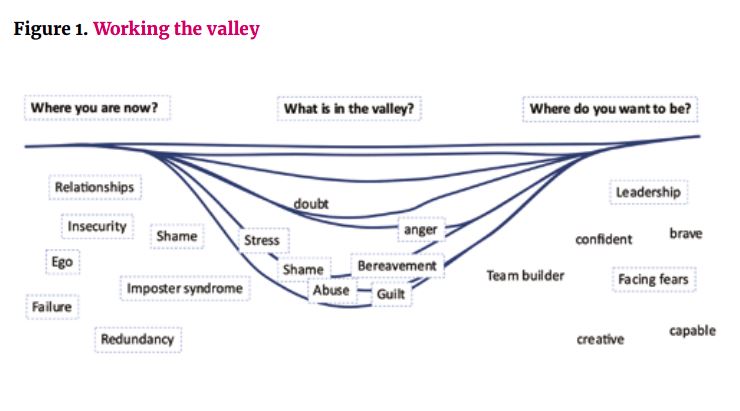

The premise behind my model is that we all have a story, and this story can limit our abilities to be all we can be. The story we have been told, or experienced, can create a valley between where we are and where we want to get to – in other words, our goal.

The use of a visual model supports the client to access both hemispheres of the brain to look creatively for solutions to the dilemma, using both logic and creativity to find a way through: thus, unpacking perceptions and meanings.4 This way of working is empowering for clients: as they begin to visualise the blocks, the solution becomes more available to them.

Figure 1

©Susie Flashman Jarvis

Working the valley - a step-by-step approach

- Stand alongside your client and ask: What is happening now? Invite them to write or draw in the valley wall all that emerges.

- Look across the valley and ask where they want to get to. Invite them to spend some time here and write or draw their ideas.

- Ask: What is stopping you? What is getting in the way? Look into the valley together and be curious. Explain that the valley depth decreases as they look clearly at the thoughts and beliefs that they hold, the memories of what was said, not said, done or not done, to them in the past, and place them in the bottom of the valley.

Next in this issue...

Figure 1 illustrates how the model works. The ‘valley’ is what stands between us and where we want to get to. It consists of events in our past, things that were said or not said, things that were done or not done. It is made up of our limiting beliefs and the assumptions we make that prevent us moving forward.

Crossing the valley means looking at the thoughts and beliefs that may get in our way. If, as coaches, we can support our clients to look back, examine and understand the past, then the valley becomes less steep and the path to the other side becomes easier to navigate. To journey with someone, we must be prepared to sit with a sense of not knowing. This is the area that requires a willingness to wait, and trust that the client knows what is best, even when they do not believe that themselves. We trust that the client is the expert in their life. We support them towards a deeper understanding of all that is preventing transformation, change and freedom, as they move towards integration of past, present and future.

For me, this is where therapy and coaching integrate. It is where many coaches are anxious about going, often with good reason. It is where trauma, abuse, loss, pain, anxiety and stress may reside.

In her book, Trauma and Recovery, Judith Lewis Herman states: ‘When the truth is recognised, survivors can begin their recovery. But far too often, secrecy prevails, and the story of the traumatic event surfaces not as a verbal narrative but as a symptom (behaviour)’5 (my italics).

Clients will often come to us with a general feeling of unease but without a clear understanding of the root of the discomfort. Working the valley is a visual tool that can help the client to literally see where their discomfort originates; where they can unpack the behaviours and assumptions that are limiting them and preventing them moving forward.

I believe that we must manage and face our own assumptions and our urge to direct the client. We all have a natural curiosity that can result in us asking a question that leads the client down a dead-end path, when truly they know the best way forward, if given the space to think for themselves.

Nancy Kline’s ‘Thinking Environment’ seeks to eliminate this issue by not asking questions that lead clients away from their own thinking. Using Kline’s Time to Think coaching method ensures no interruption and can support the autonomy of the client as they explore their valley.6 My subsequent training as a Thinking Environment practitioner has fed into the development of my model and I believe has served to enhance it.

Seeing with fresh eyes

I have discovered that when I stand with a client and look across the valley with them, a younger part of them finds permission to speak. Our stories, the ones that have happened and the ones we tell ourselves, are often held by younger parts that reside within us. Clients are unwittingly silencing their inner child. Whether this is to prevent a vulnerability, or a fear that to be wholehearted would mean that they will then have to look again at the pain, is unclear. As a therapist working with survivors of childhood abuse and domestic abuse, the challenge for me remains the same: to support my client to see what has happened through new eyes. The perpetrator is usually someone they love, and we know that the words, let alone the actions, of people they love will inform their own belief systems.5

When working with trauma, it is important that clients are not retraumatised. Providing a window of tolerance that enables them to look but not be overwhelmed can create a space for reframing of the events. This is achieved by reminding the client that they are in the present, and safe, and looking through a window to the past. They are now in control.5

Being alongside the client as they look across the valley can help them to find their adult within, to bring wisdom, insight and care to the part of them that they have not looked at clearly before, or maybe even suppressed.

If you hold your nerve, your client may well lead you. You can be the silent witness to their journey. They have survived thus far, and with some support will journey across, stopping along the way as they let go of another belief that has limited them in some way.

Victims of abuse, or those who have suffered a childhood bereavement or trauma of some sort, often carry a belief system that holds them responsible. Being free of these assumptions is fundamental to reaching the other side.

When working with trauma, it is important that clients are not retraumatised. Providing a window of tolerance that enables them to look but not be overwhelmed can create a space for reframing of the events. This is achieved by reminding the client that they are in the present, and safe, and looking through a window to the past. They are now in control.5

Being alongside the client as they look across the valley can help them to find their adult within, to bring wisdom, insight and care to the part of them that they have not looked at clearly before, or maybe even suppressed.

If you hold your nerve, your client may well lead you. You can be the silent witness to their journey. They have survived thus far, and with some support will journey across, stopping along the way as they let go of another belief that has limited them in some way.

Victims of abuse, or those who have suffered a childhood bereavement or trauma of some sort, often carry a belief system that holds them responsible. Being free of these assumptions is fundamental to reaching the other side.

Of course, the story they tell may not be about abuse. It may be about the limiting beliefs of parents, or of a boss. It may be that they failed exams or were made redundant.

Whatever is discovered in the valley is ‘grist for the mill’ and will support the client to get out of the way of themselves so they can reach the other side.

A Gestalt approach to working the valley

The use of the core conditions of empathy, unconditional positive regard and congruence can provide a safe framework for the client to explore long-held beliefs.

In The Fertile Void: Gestalt Coaching at Work, John Leary-Joyce outlines the guiding principles of a Gestalt approach to coaching.7

Rather like the core conditions, these principles invite us to think carefully about how to be as we stand with our clients: with awareness, and concern for the way we do, think and approach experience; concern for the here and now; knowing that our work is relationship centred, contextual and inclusive; and based on the principle that change is constant and only happens in the present.

Therefore, the primary role of a Gestalt coach is to create awareness of the client’s possible choices and help the client to take responsibility and ownership for the decisions they then make. In this way, they find authorship in their role, relationships, tasks, activities, in fact of their whole life.

The imposter resides in the valley

The term ‘impostor phenomenon’ was introduced in 1978 by Dr Pauline R Clance and Dr Suzanne A Imes, in their article, The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention,8 in which they interviewed 150 high-achieving women who were unable to celebrate their success, despite evidence to the contrary. Despite being esteemed by friends and colleagues, their internal ability to validate themselves was compromised.

I often find myself working with successful people, both men and women, who are unable to celebrate success, and put it down to a fluke or luck, often expecting to be found out. This can be crippling, preventing someone going for a promotion, or standing up to a bully or aggressor. It can be behind the fear of being seen authentically. In transactional analysis (TA), the drivers be strong, be perfect and try harder often create a double bind.9

In working the valley, clients may take the risk to be vulnerable and wholehearted, speaking out as they look in the valley; then these drivers can begin to diminish and lose their power.

Working my own valley

As I faced the creation of this article, I had to face my own imposter. Could I, should I, write it? What did I see when I looked in my valley? (See Figure 1). An imposter, who had frequently stomped all over my life. The result of a challenging childhood situation. The only way I had managed to deal with it was with my inner ‘drama’ child, who became stroppy and angry.

Focusing again with fresh eyes supported me to find my wise self, who could put my limiting beliefs in the right place: firmly at the bottom of my valley on which I could then build a firmer, and healthier, foundation. And from that place, I share this writing with you.

References

1 Brown B. Daring greatly: how the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent and lead. London: Penguin; 2015.

2 Brown B. The power of vulnerability. TED talk; 2013 [Online.] https://www.ted.com/talks/brene_brown_the_power_of_vulnerability?language=en (accessed February 2020).

3 Hay J. Reflective practice and supervision for coaches. London: OUP; 2007.

4 McKay S. The creative-right vs analytical-left brain myth: debunked! February 2020. [Online.] https://drsarahmckay.com/left-brain-right-brain-myth/ (accessed February 2020).

5 Herman JL. Trauma and recovery: from domestic abuse to political terror. London: Pandora; 1994.

6 Kline N. The promise that changes everything; I won’t interrupt you. London: Penguin; 2020.

7 Leary-Joyce J The fertile void. Gestalt coaching at work. London: AoEC Press; 2014.

8 Clance PR, Imes SA. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic interventions. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and

Practice 1978, 15(3): 241–247.

9 Stewart I, Joines V. TA today: a new introduction to transactional analysis. Lifespace Publishing; 2012