In a world where time and space seem to be continually contracting, it is small wonder that many coaching clients welcome the spaciousness that ‘walking and talking’ sessions outside the office can offer.

Nature as witness: a holding environment

It is now widely acknowledged that a connection to the natural world enhances our physical and psychological wellbeing; eg Ulrich’s 1984 hospital window experiment1 and Kaplan’s attention restoration theory.2 The latter identified the restorative effect on higher cognitive functioning gained through access to complex ecosystems, leading to Scandinavian government rehabilitation programmes in horticultural settings to address burnout. Earlier this year, latest findings from a Natural England survey3 suggested that a weekly two-hour ‘dose of nature’ significantly boosts health and wellbeing.

In the field of ecotherapy, Level 1 is described as ‘human-centred nature therapy’,4 with nature seen as a witness, a holding environment for the client and practitioner to use as necessary, regardless of the cost to the environment. Level 2 is about a ‘circle of reciprocal healing’,4 working at a level of ‘interbeing’ between humans and the non-human world.5 For my coaching and supervision practice, I have chosen to position my relationship with nature as ‘nature inviting us in’, reminding myself and clients of the need to respect the natural world and soften our tread on the earth while physically opening up our hearts and minds to the messages that nature may offer.

Lewis6 explored the impact of a natural setting on the psychotherapist as opposed to the client and concluded that an expanded sense of spaciousness became available to the practitioner too.

Nature as dynamic co-partner

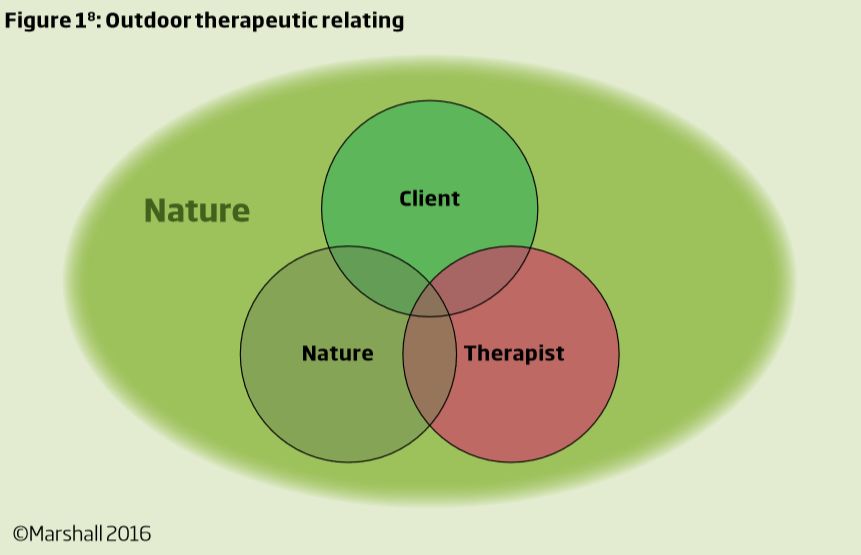

However, beyond nature as a witness, Berger7 developed the model of incorporating nature as co-therapist in the therapeutic alliance, playing a more active role by holding up a mirror to the internal emotional landscape.

Marshall8 describes the ‘eco-intimacy’ of this vibrant alliance with the immediacy of shared experiences in a dynamic environment, deepening the relationship with self and other. The unpredictability of taking a client or supervision group outdoors offers a wealth of moments that can be perceived as potential triggers for discomfort or opportunities for exploring an edge. Outdoors, those edges can easily feel magnified – for example, the client who expressed fear of large birds ahead of us venturing out to the Thames river path: we contracted for walking past the inevitable Canada geese and swans but with permission to back away or change direction if she felt uncomfortable. It was important that she felt she had agency to step towards or away from her fear in the moment, but by expressing it, she also referred to the associated shame she felt around the fear, which opened up a new aspect of inquiry around the shame. It is the process of navigation as the outer and inner landscapes meet that offers the coach, or supervisor, a richer view into the client’s world, which can be transformative for the relationship.

There is something magically synchronistic about how often the unpredictable dynamics that evolve serve as the perfect tool for the work, enabling the coach to step back to being witness, and nature to take on the role of coach (eg I had a pair of ducks come and sit in the middle of a supervision group in Regent's Park which immediately presented the perfect embodiment of the supervisee's relationship inquiry!).

Why does working with nature deepen our connection with the inner landscape?

The natural world offers a way in to our unconscious, a somatic level of knowing through hard-wired resonance (Wilson’s biophilia hypothesis)9 which accelerates internal processing, particularly for coaching clients showing up very much ‘in their heads’. While this catalytic effect can be beneficial, requiring fewer sessions for a deep sustained shift, there is also a health warning; ie emotions may surface quicker than either the client or coach are expecting, and this needs to be contracted for in advance.

Buber’s I-thou10 theory of identity mirrored in relationship offers an explanation as to why a natural setting provides such a rich backdrop for psychological inquiry: the diversity of metaphors immediately available enables clients to develop a unique relationship with objects in the moment. As those relationships unfold, they reflect aspects of the unconscious (such as the client who selected a burnt tree to represent the effect of a conflict with a fellow board member, revealing a degree of emotional scarring which suddenly became visceral for both of us – far beyond words alone). It is noteworthy how quickly many clients develop an attachment to an object that speaks to them, then revisit it between sessions as an anchor for their ongoing internal work.

There is a palpable potency about the sense of separation that the natural environment offers as co-partner. A blackbird had stood to witness a supervisee’s whole issue unfold, and I asked her, if the blackbird represented her internal supervisor, what messages might be in the blackbird’s song? Immediately she was able to separate from the story and to use the distance between to invite in new perspectives. Part of the challenge for the practitioner working outdoors is to observe and catch these moments as gifts to integrate into the work – while simultaneously being totally present for the client and attentive to their own processing. Sometimes, pointing out such opportunities as they arrive in the space can feel like a potential distraction to the client or interruption if they are mid-flow, so attunement involves choosing how and when the offer should be made. A softening of the voice, mirroring the gentleness with which the blackbird treads on the earth, enabled the observation to be heard without being experienced as an intrusion.

In a natural setting, the sense of spaciousness offers both client and practitioner the perfect backdrop for slowing down, inviting deeper noticing of the internal landscape and of respective relationships to the outer landscape in that moment. The use of movement, whether pausing or pacing, suddenly becomes an added tool; for example, modelling as practitioner a slow walking pace with the client alongside frequently generates an initial resistance in the client which, by inviting attention, paradoxically accelerates their shift to a more internal focus.

When is it inappropriate to take a client outdoors?

Taking a client outdoors may not always be appropriate; in my professional experience, psychological safety sometimes seems to be a less predominant consideration for coaches and supervisors than for therapists, and yet this is paramount, whichever modality we are operating within. Clients presenting with symptoms of stress and overwhelm may find an outdoor open space without any physical surrounding structure and accompanying sensory stimulation even more overwhelming, so this needs to form part of the initial assessment. Likewise, a client who is not yet fully engaged in the coaching process, or coaching relationship, ie not yet totally ‘in the room’, is often not ready to leave the room’s safety. For those of us who desire to work in this way, we need to consider what’s different about a natural setting that we need to attend to for psychological safety and optimal benefit. Can some of those benefits still be gained if nature comes into an indoor space? Given the current agenda around promoting positive mental health, it is also imperative that coaches who use the outdoors within a wellbeing context are equipped to do so safely.

Bringing nature in

For those situations when an outdoor space isn’t appropriate or practical, the benefits of integrating nature into the coaching process can apply equally in an indoor space.

Natural objects, such as pebbles, shells or even images, can still be used as visual and kinaesthetic channels for catalysing a somatic connection and thereby shifting the energetic state of the client. Visual natural images have been proven to reduce stress by activating the parasympathetic nervous system.11

Determining the holding environment

The qualities of the natural setting can determine its holding impact on the client; for example, a small shady woodland area enclosed by trees can feel private, intimate and containing, whereas open downs, with their vast expanse of open space, few trees and long views, can feel much more exposing and uncontaining, even potentially overwhelming for a client who is new to coaching and/or is already experiencing a sense of feeling overfull. However, for a client wanting internal spaciousness to shift perspective and unstick some unhelpful narratives, an expansive space inviting movement and physical freedom can be a powerful vehicle for inquiry. Even then, a grassy dip in the hillside where we can sit together can offer a surprising degree of physical and emotional containment. Working at the point where the urban and rural worlds meet can also be powerful: where is the clash of systems in the client’s world?

What’s different in practice that coaches need to attend to?

My advice to coaches and supervisors working outdoors is to pay particular attention to what I call the ‘3Cs: Contracting, Containing and Connecting’ – which all require some adjustment from indoor practice. ‘Contracting’ needs to include permissions concerning unpredictable events, and the client’s particular fears or vulnerabilities. ‘Containing’ means ensuring that the client feels energetically held in the space through regular checking-in and managing proximity between coach and client, while securing privacy. ‘Connecting’ requires the coach to soften the boundaries between self and the natural world so that the dynamic and spontaneous gifts available are noticed and integrated, if appropriate, and to invite the client to do the same.

What’s the added value for supervisees from being outdoors?

Group supervisees have the additional benefit of observing nature interact with their fellow group members:

‘By positioning the work as Nature inviting us in, this gave a somatically different aspect for us to step into – our senses were awakened so we could notice the metaphors Nature was presenting to each of us. When I was too wrapped up in my thoughts, I missed what Nature was offering!’.

Integrating nature in an organisational context

I have experienced some resistance to this way of working from coaching leads in large corporate organisations, which act as a barrier to internal coaches drawing on its potential or clients reaping the benefits. Examples I have heard range from: ‘There’s not enough time for it’ to: ‘It wouldn’t address serious issues, it’s just tree hugging’ to: ‘You need to be in the country’ (when a couple of trees and a view of the sky will suffice!). Hopefully, over time, the bottom line benefit of fewer sessions will make employers stop and listen to its unique value – as an enabler for positive mental health; a catalyst for deep, sustained change and a vehicle for softening our collective tread on the earth.

Catherine Gorham is accredited as senior practitioner coach and supervisor, EMCC, and Fellow, CIPD. Her private practice includes the role of Master Coach for Frontline, a charity training social workers. catherinegorham.co.uk

References

1 Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984; 224: 42–421.

2 Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: towards an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1995; 16:169–182.

3 Carrington D. Two-hour ‘dose’ of nature significantly boosts health – study. [Online.] Guardian Online, 13 June 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/ environment/2019/jun/13/two-hour-dose-natureweekly-boosts-health-study-finds (accessed 6 August 2019).

4 Buzzell L. The many ecotherapies. In Jordan M, Hinds J (eds). Ecotherapy theory research & practice. London: Palgrave; 2016 (pp70–82).

5 Conn LK, Conn SA. Opening to the other. In Buzzell L, Chalquist C (eds). Ecopsychology: healing with nature in mind. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books; 2009 (pp111–15).

6 Lewis R. A qualitative study of psychotherapists’ experience of practising psychotherapy outdoors. Dublin Business School; 2017.

7 Berger R, McLeod J. Incorporating nature into therapy: a framework for practice. Journal of Systemic Therapies 2006; 25(2): 80–94.

8 Marshall H. Taking therapy outside – reaching for a vital connection. Keynote presentation at CONFER Conference, Psychotherapy and the Natural World; 2016. Illustration reproduced with permission.

9 Wilson EO. Biophilia: the human bond with other species. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1984.

10 Buber M. I and thou. Translation by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons: 1971.

11 Dockrill P. Just looking at photos of nature could be enough to lower your work stress levels. Sciencealert. com 23 March 2016. [Online.] https://www. sciencealert.com/just-looking-at-photos-of-nature-could-be-enough-to-lower-your-work-stress-levels (accessed 6 August 2019).