Events at Stafford Hospital and findings of the Francis Inquiry1, further compounded by the Keogh Mortality Review2, are sharp reminders that we cannot assume good standards of care exist in NHS services.

The report from the Francis Inquiry exposes an unhealthy culture, stating that ‘the demands for financial control, corporate governance, commissioning and regulatory systems are understandable… but it is not the system itself which will ensure that the patient is put first day in and day out. It is the people working in the health service1.’

Looking beyond Stafford, to the NHS system that Francis refers to, we see it is a system operating under the strain of high expectation and limited capacity. There is a finite budget, growing need, and growing costs associated with technological advance, an increasing ageing population and increasing prevalence of conditions such as obesity and diabetes. It is unsurprising, therefore, that the problems at Stafford Hospital are not isolated incidents. The NHS, and, by association, services commissioned by the NHS, are clearly vulnerable, and psychological therapy provision is not immune. This was substantiated by the BBC Three investigative documentary aired in July, Failed by the NHS3, that exposed how some people with mental health problems were not receiving adequate care.

In addition to analysing systemic failings, the Francis Report1 also focuses on the role of healthcare practitioners in putting patients first, coining the phrase ‘culture of care’. If you have ever found yourself questioning whether the NHS system is enabling you to work to the standard of care that you aspire to, then you may already have an insight into where NHS-funded therapy provision could be vulnerable.

This article explores some hypothetical scenarios where ethical dilemmas evolve from the pressures of the system, while offering reflections on the learning we might take from the Francis Inquiry. The aim is to provide readers with an opportunity to reflect and consider how to work with other practitioners, managers and/or commissioners to more effectively manage the clinical and financial dilemmas together, striking the best possible balance for patient care and safety.

Francis states that ‘it should be patients – not numbers – which count’. In reflecting on scenario one, we might question whether the numbers of sessions and waiting times count more than the patients. The scenario is, however, not that straightforward. For example, there is the real concern that if the service does not take these referrals, it will affect patient care. Perhaps the referral team believe they are doing the best they can by offering people some service rather than no service. The service manager may be driven by meeting the requirements and targets of the Service Level Agreement to ensure commissioners are satisfied and continue to invest in the service, fearing that the service could be lost altogether.

It could be argued that the service is set up to fail by an unrealistic Service Level Agreement and all parties are trying to make the best of it. So we must consider what the commissioners’ role is in this scenario. It may be that the service manager is reporting the problems and trying to negotiate, but the commissioners may have their hands tied due to budgetary constraints and the need to meet centrally driven targets. We have to question though: how would all parties feel in the event of a suicide or similar critical incident? Suppose an investigation found that inappropriate referrals had been accepted, a counsellor had been working beyond their competence, the course of therapy was too short, and therapy ended when the client was vulnerable. How would they each justify their decisions?

To avoid such a critical incident, the learning from Francis would suggest that the different parties need to take individual and collective ownership of the shared problem. An open dialogue about the skills gap and training needs, both for the team making referrals and for counsellors, may result in training that both improves the referral process and equips counsellors to work competently with more complex cases. Improving links with secondary care and psychiatric support might be another part of the solution. It may be, however, that solutions cannot be found to address all the implications of the current demands on the service. Working together, the referral team, counsellors and managers may find they are better able to present a cohesive case to commissioners when negotiating the Service Level Agreement, particularly if they can demonstrate they have innovated and implemented some solutions already. They may be able to negotiate for flexibility to work with some clients over more than six sessions on the basis that this would be offset by some clients requiring less than six sessions (and so the service would still be aiming for an average of six sessions per client). There follows two more scenarios for reflection.

What do you think about these scenarios? Do you identify with any of the content? How might the counsellors in these scenarios approach their manager? A clear theme in all three scenarios is the potential for counsellors to feel unsupported in giving patients an appropriate level of service. This resonates with some of the evidence submitted to the Francis Inquiry. For example, a nurse made this comment:

‘… in some ways I feel ashamed because I have worked there and I can tell you that I have done my best, and sometimes you go home and you are really upset because you can’t say that you have done anything to help.’ The nurse went on to comment: ‘There was not enough staff to deal with the type of patient that you needed to deal with, to provide everything that a patient would need. You were doing – you were just skimming the surface and that is not how I was trained4.’

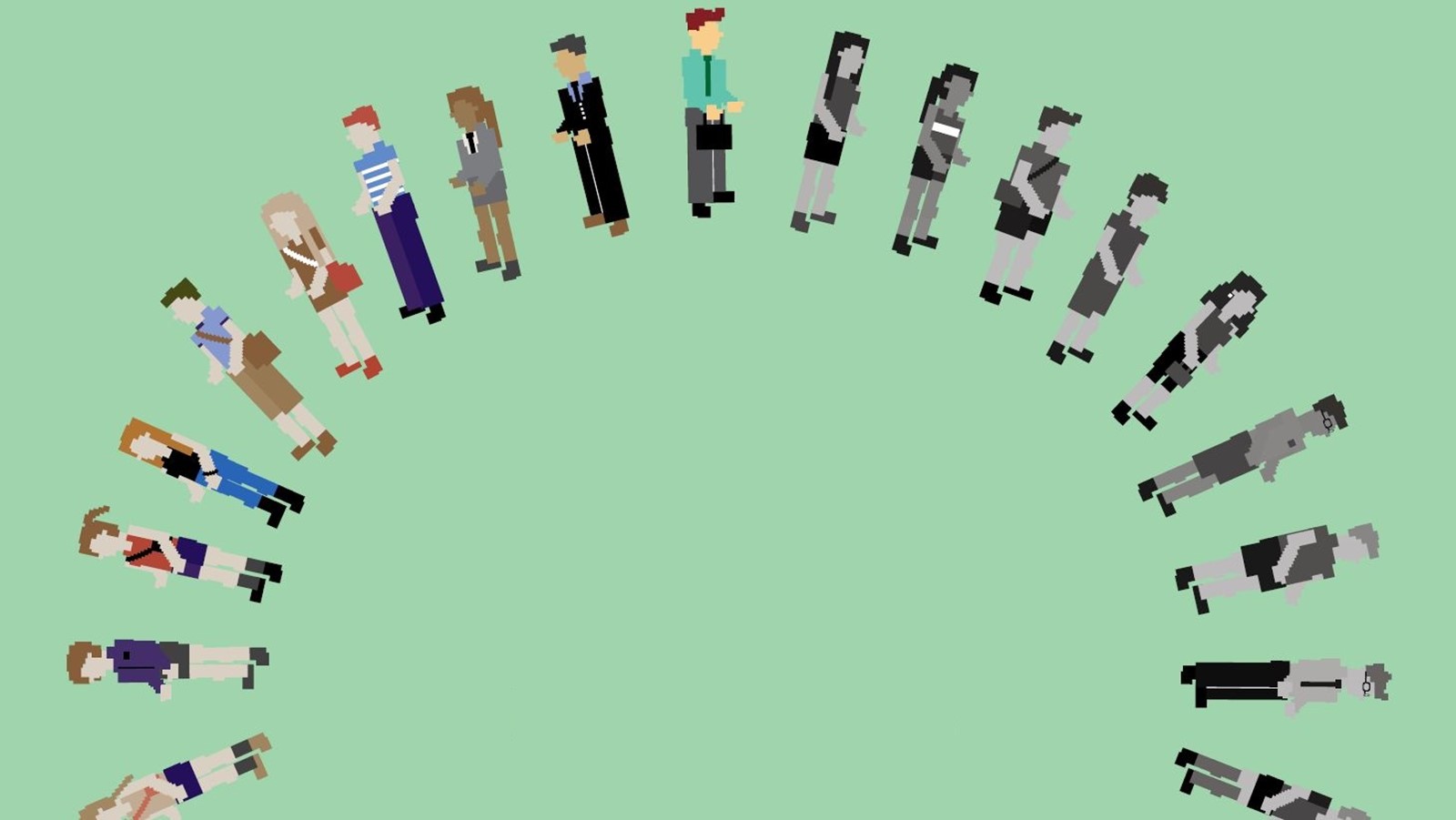

There are 290 recommendations in the full Francis Report that are essentially supporting the vision of service design and delivery with good patient care at the heart. The Keogh Mortality Review identified some similar themes to Francis that have also been the rhetoric of UK governments and reflected in policy for several years (see Figure 1). Many would argue that the NHS system is already designed to enable the delivery of services with patients at the heart. The concepts of effective service design: safe, ethical and effective practice, and monitoring through evaluation, have been part of NHS language for decades. It is the language of clinical governance.

Figure 1: Five improvement areas - based on recommendations in the Keogh Review2

Workforce

|

Governance and leadership

|

Patient experience

|

|

Safety

|

Clinical and operational effectiveness

|

So what is needed to make the vision a reality? Francis argues it is not the system that turns a vision into reality, it is the people. For example, collating targetbased statistics is not sufficient in itself to understand how a service is performing; it is vital that relevant data and statistics are provided with the real stories behind them. The perspectives of patients need to be heard by practitioners, managers and commissioners. Tools such as Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and Patient Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) could help; so might online facilities such as Patient Opinion, where clients can post their comments, and of course, the newly forming local Healthwatch may be able to leverage change. Opportunities do exist, but they can only make a difference if they are implemented effectively, findings are reported, and action is taken where required.

Put simply, it’s not what you do but the way you do it that makes the difference. But it can be a battle: evidence submitted to Francis clearly demonstrates how hospital staff felt powerless to challenge or change the system. The culture became one of intimidation and bullying; no one took responsibility, instead choosing to blame others or take the path of least resistance. It could be argued, however, that the high-profile national debate arising from the work of Francis and Keogh is presenting an opportunity to do things differently as no NHS-funded service wants to be next in the spotlight.

So, what can you do to help ensure there is a ‘culture of care’ in your service? One of the recommendations in Francis is that staff in all services provided or contracted by the NHS uphold the values of the NHS Constitution5. Are you familiar with the NHS Constitution? If you feel unable to uphold its values in your work, then perhaps this recommendation by Francis provides a springboard for dialogue with your manager or supervisor? A general understanding of the Francis and Keogh findings and recommendations could be useful too.

Another tool that may help you engage in dialogue is the BACP Ethical Framework. It is likely that your contract of employment requires you to be a member of a professional body and abide by such an ethical framework. If you can give examples of where your employer’s expectations are not aligned with the Ethical Framework, this could be another basis for a conversation. Dr Alistair Ross, Chair of BACP’s Professional Ethics and Quality Standards Committee, comments: ‘The Ethical Framework is a touchstone for members, supporting their professional and ethical practice; as such it has maximum impact when used proactively to prevent problems from arising. For members working in the NHS, it can facilitate supportive engagement with employers when discussing areas of concern.’

If you do decide to raise concerns with your manager, how will you approach this? The scenarios in this article and learning from Francis show that the problems can be at all levels of the system, with all parties feeling helpless. What can you do to engender a collegial approach to solving the problems? There will be a reason for the status quo; can you build rapport with the other parties and establish dialogue to help you understand their position and dilemmas? Shared understanding may lead to a solution or, at the very least, help identify ways to mitigate and manage risk. In taking the collegial approach, it remains important to be assertive; it may be that you feel no alternative but to make a complaint because of the severity of your concerns. Peter Jenkins’ article on whistle-blowing, which follows, explores the rights of employees who raise concerns and the potential personal and professional implications of taking such an action.

Louise Robinson is the healthcare development manager for BACP.

All the scenarios included in this article are hypothetical and do not reflect any particular service or client case study.

References

1 www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com

2 www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/bruce-keogh-review/Pages/Overview.aspx

3 BBC Three. Failed by the NHS. Broadcast 29 July 2013.

4 www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_document/robert-francis-kingsfund-feb13.pdf

5 www.nhs.uk/choiceintheNHS/Rightsandpledges/NHSConstitution/ Pages/Overview.aspx