In this issue

Features

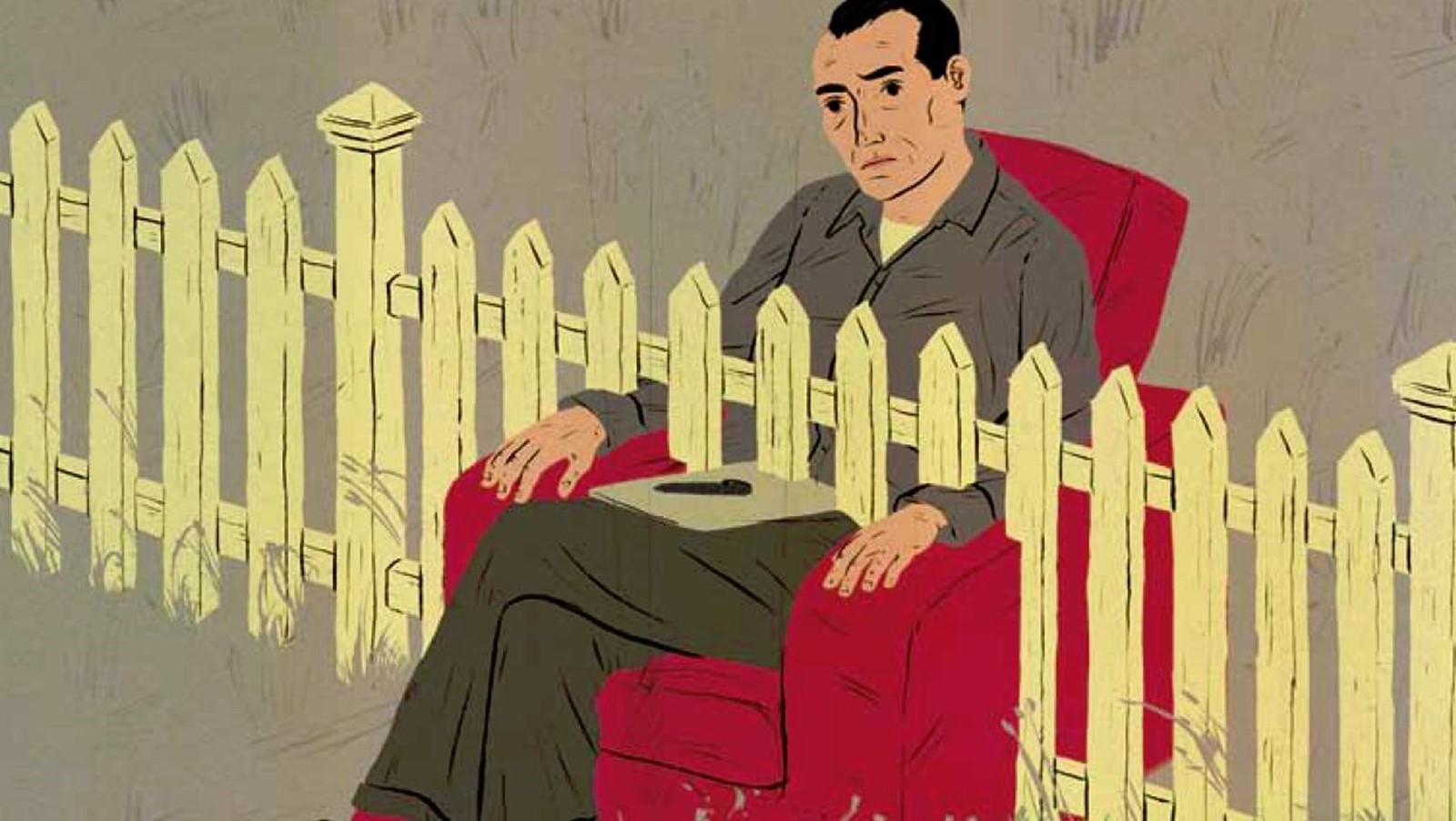

Boundaries and boundlessness

Can an overemphasis on boundaries act as a block to authentic relationship between therapist and client?

Emotional needs and group therapy

Group therapy may fail to provide focused attention to the individual but there are other areas in which it excels.

Dementia: a ‘death of the mind’

A psychodynamic approach to thinking about those who suffer from dementia and the unconscious fears that may affect their carers.

The agony and the ecstasy

A review of Mike Leigh’s latest film, Another Year, which features an NHS counsellor as one of its main characters.

Regulars

In practice

Kevin Chandler: Not just another day

In the client's chair

Orla Murray: Writing about therapy

In training

Alex Erskine: Ready for training clients?

Dilemmas

Managing boundaries

Day in the life

Aaron Sefi

Questionnaire

Gregor Henderson

All articles from this issue are not yet available online. Members and subscribers can download the pdf from the Therapy Today archive.

Editorial

In the last few years I have noticed how the word ‘boundaries’ appears in discussion of counselling and psychotherapy practice with increasing frequency. We generally talk about boundaries in a positive way, lines which we all agree must not be crossed, such as talking socially about a client or telling a client that you find him or her attractive. There are other boundaries, of course, which are more controversial, such as whether you should allow a session to run over for 10 minutes, visit a client in hospital or accept a gift from a client.

Tim Bond has written of the ‘ongoing tension between attending to client safety and risk-taking by both clients and therapists that is required for therapy to be effective’ (Towards a new ethic of trust’, Therapy Today, April 2008); and others have argued that the necessary ‘Do no harm’ might easily slide into a ‘Take no risks and play everything by the book’ approach, which is hardly in the spirit of the BACP Ethical Framework as I understand it.

But how much have we questioned where the notion of boundaries actually comes from or considered the impact that an overemphasis on boundaries might have on newly qualified or inexperienced practitioners? Nick Totton addresses what he sees as the profession’s current obsession with boundaries in his article ‘Boundaries and boundlessness’. He argues that the theory of boundaries in fact originates in work with survivors of sexual abuse, and questions therefore its appropriateness as a way of thinking about other aspects of therapy, such as times, fees and terms of address. Totton reminds us that the humanistic therapies developed as an approach which emphasised a warm and authentic relationship, partly in reaction to what was seen as the rigid structure and formalities of psychoanalysis. Will the practitioners of the future cease to be able to work authentically and flexibly for fear of ending up in the professional conduct system?

Sarah Browne

Editor