Loneliness has been much in the news in recent months. In March the Campaign to End Loneliness and the Department of Health hosted a summit to tackle loneliness in older age. Speaking at the summit, Minister of State for Care Services Paul Burstow said: ‘We are living through an epidemic of loneliness and if we don’t start to take action, it will have huge consequences for individuals and for our health and social care systems.’

These consequences of loneliness are considerable. Loneliness is said to be as bad for one’s health as smoking or obesity. It can lead to high blood pressure. People with strong relationships with friends and family are 50 per cent less likely to die young than those who are socially isolated.1

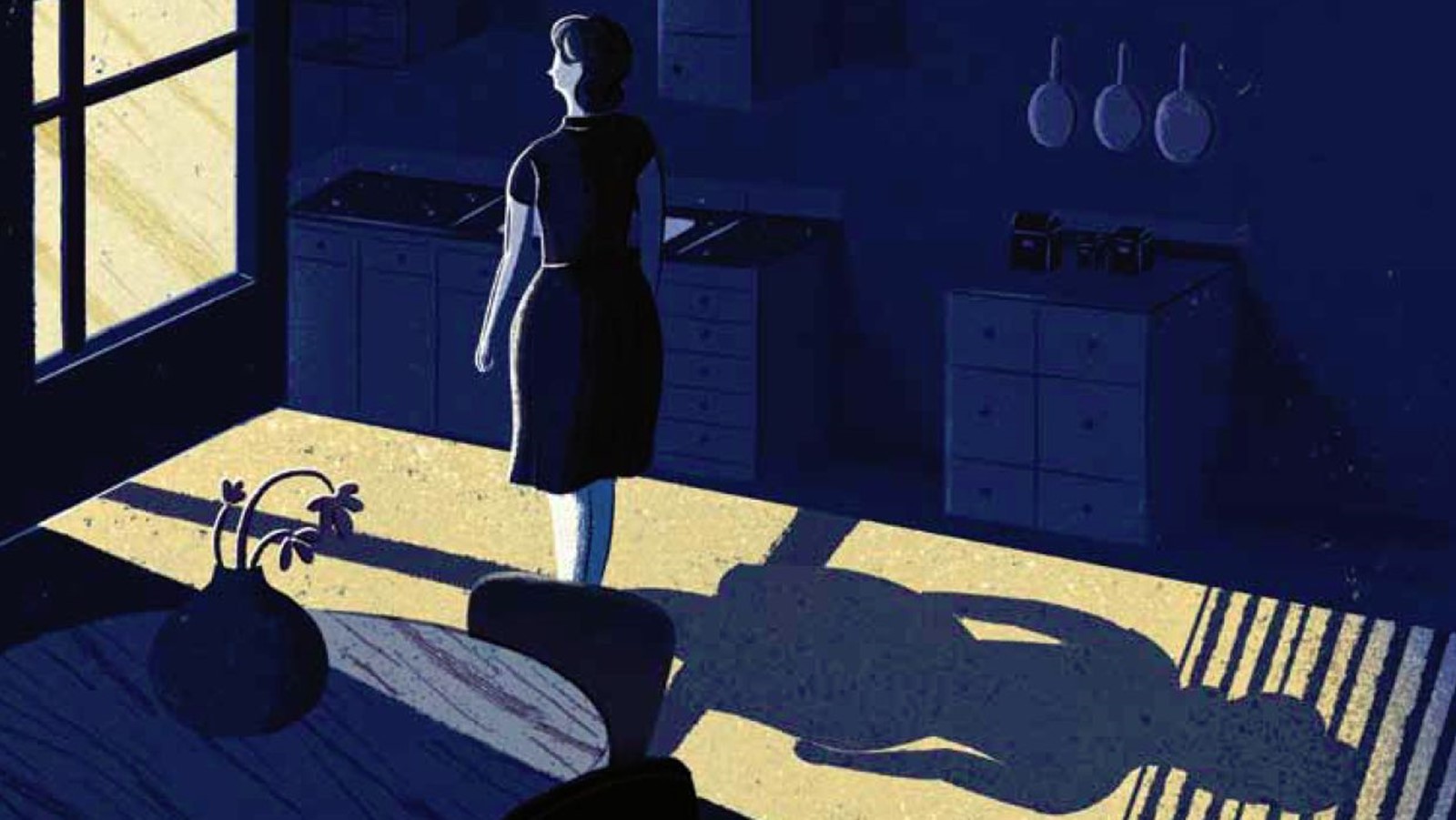

Eight million people in England live alone. Circumstantial evidence seems to suggest that the explosion in social networking has not led to a reduced experience of loneliness. Indeed, paradoxically, the consequent reduction in direct human contact may exacerbate the problem for some people.2

Importantly, loneliness has also been identified as a significant cause of depression.3 A recent study in Finland found that living alone is associated with much higher antidepressant use.4 In older people, loneliness and thence depression often stems from poor physical health, which limits their ability to participate in social and community life.5 Increasing fragmentation of the family means older people are less likely to have children and grandchildren living nearby.5 A research review by the Mental Health Foundation explains how people can become locked into a vicious cycle of loneliness and mental distress, whereby the depression and stigma associated with social isolation effectively prevents them breaking free of it.5

People who go to their GP complaining of depression are very likely to be given medication, when the depression is in fact a symptom of loneliness. Loneliness carries a huge social stigma. Arguably, it may be more socially acceptable to admit to feeling ‘down’ or depressed than to tell your GP you are lonely. Or it may be that the GP simply does not ask.

Given that the depression itself is a symptom of another problem, medication alone is unlikely to resolve it. Horwitz and Wakefield argue that symptoms associated with depression, such as fatigue, loss of appetite and low mood, are too often wrongly diagnosed as depressive disorder when, in fact, they are normal expressions of sadness and grief.6 Could there be other ways to help people who are experiencing emotional distress because of loneliness?

Working with depression and loneliness has long been close to my heart in my practice as a counsellor and psychotherapist. I see a link between boredom, depression and loneliness. Sometimes feelings of loneliness and depression may be suppressed or blocked by manic activity, or substance or alcohol use; they only become a problem when the person is unable to access these distractions. When we are forced to sit with inactivity, when we have to stay with our boredom and we can’t escape it by distracting ourselves with new busyness, the mind then has to come to grips with being still. All kinds of uncomfortable emotions can then rush into the space. A wise person once told me: ‘When the mind goes still, it is asked to be silent. When it can’t hear itself talking any more, then it becomes very frightened. In the silence, it fears it will die.’

From my experience, I would add to this that the mind then feels despairing and alone, and may recall previous experiences of this existential loneliness.

Working on ourselves

How, then, to go forward, if medication is not the answer? One way might be to change our attitude towards loneliness and the uncomfortable feelings it can trigger. By working on ourselves, we can learn to a) accept those feelings and know that they will pass in time, b) learn – at least some of the time – to turn loneliness into an experience of being alone with ourselves in a loving and meaningful way, and c) use solution-focused and CBT-based techniques to increase our sense of self-worth and social contact. These can indeed be helpful and fruitful strategies, yet, in my many years of research, I have found they often have only limited effect.

Why should that be so? I would argue, based on my own work, that loneliness goes far deeper than the experience of social isolation; that it often arises out of a lack of secure and loving attachments in childhood and is thus hard-wired into the brain. As with all attachment issues, the individual then finds it difficult to open their heart to deep and meaningful relationships and becomes locked into a perpetual emotional ‘loneliness’, even when surrounded by other people.

Needless to say, self-esteem improvement techniques will therefore be of limited use. However, I have observed that groupwork does help. It does this, I would argue, by normalising the experience of being lonely and so reducing the feelings of shame. It also helps to heal those old wounds by allowing the individual to experience the love and empathy of the group. I would argue that the group experience provides a safe – if at times challenging – environment for my clients to experiment with forming relationships and establishing secure attachments.

Sculpting workshop

And yet, I have still sometimes felt that even this does not go to the heart of the matter. This led me to consider other ways of addressing loneliness. In my training as a transpersonal psychotherapist, we used sculpting: a technique where a client re-enacts a particular moment in their history, with the help of other group members. The client represents him or herself, and chooses group members to represent the other players involved in the situation they want to enact.

The client ‘sculpts’ the scene by placing, for example, the representative of an absent parent at the far end of the room, back turned, looking out of the window, away from the client who sits alone on the floor. Sculpting differs from psychodrama: it is performed in silence and is static; the emphasis is on the individual experiencing the feelings the situation provokes and it being witnessed by the group. After some time, the sculpt ends and the client reports how it felt to stay with those difficult feelings. Group members are also invited to share how they felt in their representative role. Typical feedback from the uncaring parent in this scenario might be: ‘I just did not feel present. I felt I did not want to be here and could not connect with you.’ This might sound cruel but it is often a real breakthrough for the client, who may then think: ‘I spent all those years thinking something was wrong with me that I felt that way, but now it all makes sense.’

Finally, the group feeds back, often with a lot of warmth and empathy for the client as they witness his or her pain. This profound process of being seen and held, with warmth, is very valuable to people whose experience of other people has been one of loneliness and isolation.

This sculpt is then followed by a ‘reframing sculpt’, in which the client is encouraged to recreate the scene as they would have liked it: with, for example, the mother figure sitting with him or her, playing. While this might sound weird, and isn’t true in the sense that it didn’t happen that way, it is a ‘surplus reality’ (to borrow the psychodrama term): it shows how life ‘should’ have been and is very healing. The same process of sharing then follows.

Sometimes, in my experience, the reframing sculpts do not flow so easily. This might be due to clients being too shy/ashamed to ask for something they really want (like a long embrace or having their head stroked). Or it might be that the love is just not flowing: the participants are struggling to be unconditionally loving. This experience will make sense to those familiar with Bert Hellinger’s transgenerational family constellation work.7 He suggests that disruptions to the flow of love in previous generations of a family system (for example, due to guilt, or illness, or where a ‘black sheep’ has been erased from the family history) also disrupts the flow of love within the family in the present. Parents and children in subsequent generations are unable to form a deep emotional bond, leading to an absence of safe, loving attachments.

This may sound bizarre but I have – with the permission of group participants and with the clear understanding that we are working in the spirit of inquiry – started to introduce some of Hellinger’s ideas to my sculpting groupwork. The results have been astounding.

One client, in her 50s and an experienced bereavement counsellor with many years’ experience of self-development and co-counselling, wanted to work on her experience of loneliness. She sculpted a scene to enact her close relationship with her father and her very distant relationship with her mother, who had had mental health problems and was a frightening, cold figure in the background, who would not connect with her daughter. The client herself is of Jewish descent.

Following Hellinger, we worked on the mother’s parents’ experiences as Jewish people in Nazi Germany. We honoured them as victims of the Holocaust. This had a profound effect on the mother’s representative. She changed from feeling almost devoid of life force and suicidal to making a real heart connection with her daughter. It was very touching to witness the client meeting her ‘true’ mother and, for the first time in her life, feeling loved and cared for. The group was in tears, sharing this special moment as she emerged from loneliness into connectedness. She said: ‘It is like I met my mother for the first time.’ Her mother had died many years ago.

Another client, having worked on her relationship with her parents, was able to see that there had been a role reversal in her relationship with her own children. She had – unconsciously – pushed her sons into a parental role by encouraging them to experience her as weak and vulnerable. After the sculpt had addressed these disturbances in the ‘flow of love’, to borrow Hellinger’s term, the role reversal changed. The sons had not been told that she was doing this work but happened to ring her in the evening after the group workshop. The client reported that the dynamics between them had completely shifted. She felt loving and strong and fully connected with her boys in the role of their mother.

A healing experience

These are just two brief examples of the deep and lasting work that can occur in a sculpting workshop. Not only does the sculpting show up disturbances we might not have seen in one-to-one work; the deep witnessing and sharing that takes place in the group can also be deeply healing. Clients receive a lot of love and empathy and, by acting as representatives in another person’s sculpt, are able to participate and contribute to another person’s healing in a very profound way. This is important as clients who are struggling with loneliness often long for the opportunity to flow love into another person’s life.

Working with a group of people in this intensive way affords us resources we do not have at hand in individual ongoing work. Moreover, while it is not the main aim of the workshop, a ‘side effect’ of the deep sharing is that some clients form friendships with each other and continue to keep in touch after the workshop ends.

I have sometimes had reservations about clients attending too many workshops, and have questioned their long-term benefits. Nevertheless, I have found that, when integrated in the holding frame of individual therapy, sculpting or constellation workshops, through the group process and the possibility of experiencing warm and loving attachments, can be very healing in addressing loneliness and depression. The participant is encouraged to really take in, for quite some time (mainly through eye contact), the love from the representative of the parent. They have time and space to experience this fully, to open their hearts, cry and feel held by both ‘the parent’ and the group. This process goes some way towards connecting up new pathways in the brain and disconnecting the old, ‘hardwired’ loneliness. The experience can leave clients feeling more hopeful, less depressed and more positive about their ability to make meaningful connections in the future.

© Madeleine Böcker 2012

Madeleine Böcker, MA, Dipl Psych, MBACP, is an accredited transpersonal psychotherapist. She worked in a private psychiatric hospital in York for six years, and has been working in private practice for eight years in Maida Vale, West London, as well as running group workshops. Madeleine has a strong background in research and has been working for a number of years on the connection between loneliness and depression. She also works systemically and has an interest in Jungian Alchemy. For further information, please visit: www.psychotherapywithheartandsoul.org.uk

References

1. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010; 7(7): e1000316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1000316

2. Kim J, LaRose R, Peng W. Loneliness as the cause and the effect of problematic internet use: the relationship between internet use and psychosocial well-being. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2009; 12(4): 451–455.

3. Pulkki-Raback L, Kivimaki M, Ahola K et al. Living alone and antidepressant medication use: a prospective study in a working-age population. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12: 236. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-236

4. VanderWeele TJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. A marginal structural model analysis for loneliness: implications for intervention trials and clinical practice. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 2011; 79(2): 225–235.

5. Griffin J. The lonely society. London: Mental Health Foundation; 2010.

6. Horwitz AV, Wakefield JC. Loss of sadness: how psychiatry transformed normal sorrow into depressive disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

7. Hellinger B, Gunthard W, Beaumont H. Love’s hidden symmetry: what makes love work in relationships. Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen; 1998.