Colin Feltham: It’s very interesting that loneliness is said to be as bad for health as obesity and smoking, yet it doesn't receive nearly the same health promotion publicity as those topics. Are we likely to see more focus on it soon?

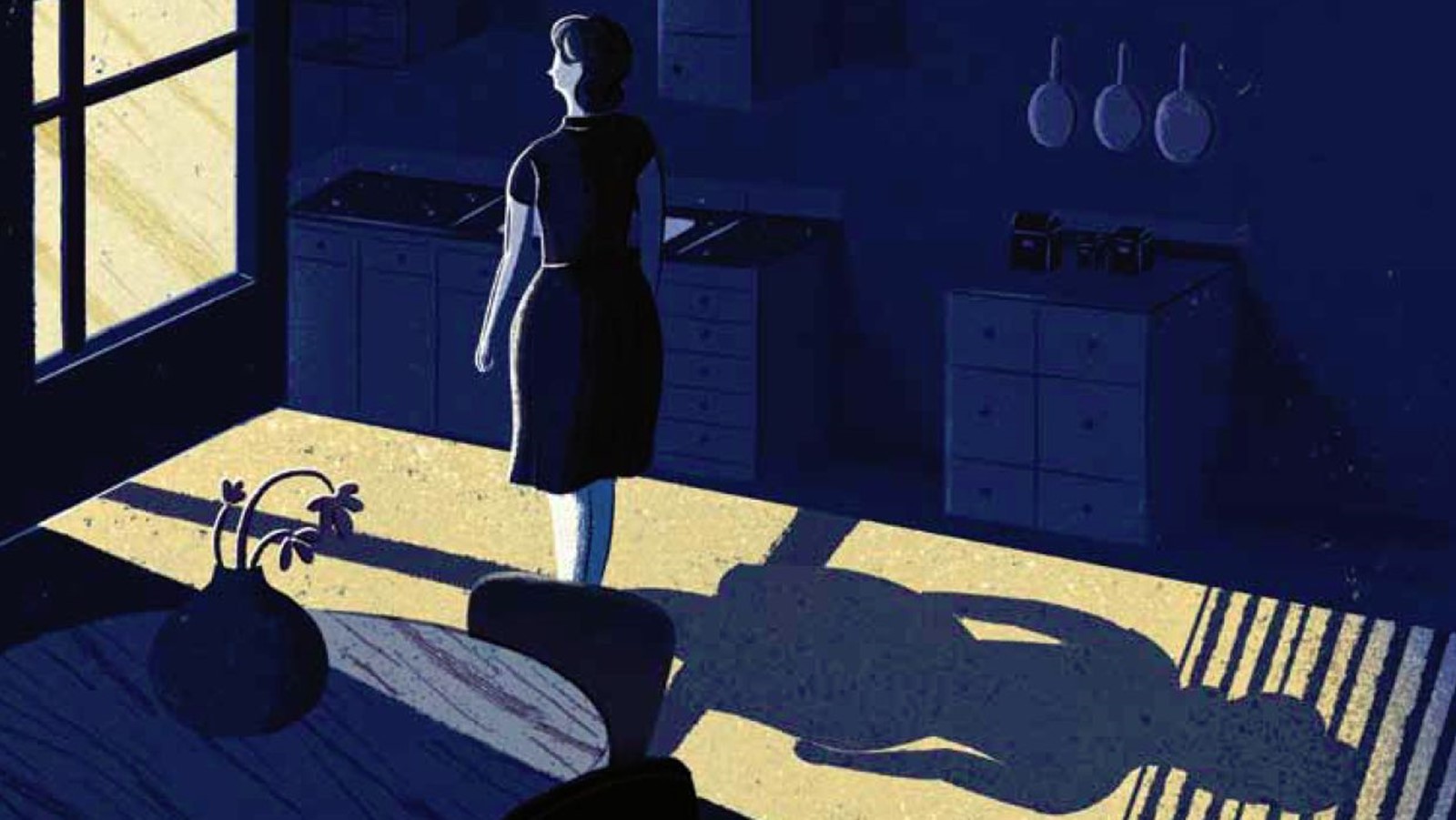

Madeleine Böcker: That is an excellent question. My personal answer would be, ‘I doubt it,’ due to the stigma of loneliness, which I refer to in the article. Sadly, it still seems so much easier to get help for a visible condition than an invisible one like ME, depression and, indeed, loneliness. Of course ‘feeling invisible’ is often part of the experience of loneliness, so it is all the more important that we start talking about it. I would love to be proved wrong!

Given that there are eight million people in England living alone, this sounds like an epidemic of loneliness and its poor health consequences waiting to happen. What ideas do you have about the different causes of such massive isolation, about gender and age factors and so on?

Well, I’m not a sociologist. However, some of the articles I mention talk about the elderly, and most of us seem to be aware, to some extent, of people living longer and having mobility problems that confine them to their houses. A friend of mine recently said, ‘There are no elderly people in London.’ What is your experience? I have lived all over London and, generally, I would agree. Though I would say that one seems to see more elderly using buses in the suburbs. Among the elderly, often women are more affected by loneliness, as they tend to become carers and outlive their partners.

However, increasingly the demographic seems to be changing and we are getting more single households among younger people, as well as the middle-aged. More people are working from home. It is very interesting how much the experience of isolation seems to be linked to where one lives within the UK. Look at this map provided by the BBC comparing 1971 with 2001.

Most worryingly in many ways, we seem to get a lot of children and teenagers texting and skypeing each other, rather than actually meeting up (this goes for adults, of course, too), with all the poverty of relating that might entail.

Can you unpack a little more the links between loneliness, boredom, depression, increased risk of hypertension and death (and sometimes substance abuse) and stigma?

This would be quite a long answer, I fear, and I am not sure where to start and where to stop. As I outlined in the article, I think that a prolonged period of boredom can often throw people deep into loneliness, whether or not they are actively aware of this. Boredom can have a quality of wanting to be entertained by the outside world, as one does not feel OK with being with oneself – the self in these moments might be experienced as ‘not enough’ or ‘empty/meaningless’. A deep unease about being with one’s inner world or fear of difficult feelings might emerge. Many people living by themselves seem to defend against this as best they can by constantly having the radio or TV on.

Another way of trying to defend against this can be alcohol or other substance abuse – see, for example, Groff’s work on addictions – and comfort eating, as a way of desperately trying to ‘fill the void’ – the inner experience of emptiness that comes with boredom and loneliness. If these feelings do surface and the individual feels low, this is often confused with a generalised depression.

With regards to hypertension and death, I would point you to the study quoted in the article, but on a more anecdotal level, do you remember as a child going to the zoo and watching caged tigers pacing restlessly? If we think of ourselves as animals, being away from our pack makes life less safe. Being by oneself might lead to anxiety and stress. Often people tell me they feel like a ‘caged animal’, and they experience some relief sitting in a coffee shop with strangers.

Sometimes clients who live alone report feeling vulnerable or frightened when ill: ‘If something happens to me will they find me dead after two weeks with my face having been eaten by the cat?!’ The social stigma of being alone (which neatly seems to translate in many people’s head into ‘I am unlovable and boring, otherwise I wouldn’t be lonely’) adds more stress. I am not surprised about the studies pointing to hypertension and premature death. Also, how often do we hear that, when one partner of a couple dies, the other one follows quite soon after, even if their health wasn’t previously apparently in crisis?

In your experience, how readily can most people who are lonely use meditation to accept their feelings, appreciate aloneness and apply solution-focused and CBT techniques to help them overcome the psychological consequences of loneliness?

This is a complex question, and ought to be answered on many layers to do it full justice. However, to be brief, in my experience most people who do not have some sort of spiritual framework/experience of meditation struggle with this. When I first conceptualised the workshop, I was reminded of what Heidegger said: ‘The dreadful has already happened – we realise we are alone.’

Some are actively opposed to ‘acceptance’ as they want to change their situation; others feel it is meaningful in itself, or indeed easier to remain there than to change. So, with regards to meditation, I find that those who have a non-dualistic spiritual context, or those who are interested in angels, guides, ancestral voices etc, do find it easier to transmute personal loneliness/aloneness and to connect with themselves first and their spiritual framework in loving way, which makes them feel loved and held more easily.

For other clients, it is a much more ‘hands on’ journey, using ideas derived from CBT, Gestalt or Transactional Analysis to challenge old negative beliefs about themselves in order to re-enter the world with more confidence, hope and openness to relationships. Last but not least, one of the main things we seem to be doing in therapy is ‘being with’, isn’t it?

I feel that both witnessing and being ‘with presence’, to borrow the Quaker term, are valuable to our clients. Yet, if you pin me down, in my experience it is a struggle to befriend aloneness or to make changes in one’s life just with the strategies you have mentioned. That’s why I felt a group and a holding environment are important.

I'm not clear about the evidence showing associations between poor childhood attachments and later 'hard-wired' attitudes. Can you say a little more about this?

I am glad you ask that, Colin. I’m aware of a bit of trickster energy in me that wrote this. I am not clear about the evidence. I am mainly working from my own observations and drawing on conversations with colleagues. I am hoping to do more research on this in the future, but I am also hoping to provoke some reactions. I would love to hear if anyone has come across much research on this topic.

Speaking from observation, it seems to me that people who have come out of childhood with more or less secure attachment styles are less likely to be lonely as adults. The fact that their general attitude to relationships is often reasonably optimistic leads them to approach relationships/friendships in an open, positive way, which in turn makes it more likely they will flourish.

People who have formed more ambivalent/insecure or avoidant attachment styles seem to be less optimistic about being able to form loving, deep relationships/friendships, which can manifest as a self-fulfilling prophecy time and time again. Often, but not always, people then either try to overcompensate (I shall return to this later), or become more isolated/lonely. Of course this is only a generalisation and other factors come into play, too.

The work you describe, of sculpting in groups and Hellinger's transgenerational family constellation work, sounds moving. Can you tell us more about how these are used, what results have been found, and what evidence there is that their effects are long-lasting?

When I first submitted the article to Therapy Today, I am sure I had a little disclaimer in there, clarifying I was not going to argue for or against the validity of constellation work, but merely sharing my observations. In a way, I would like to remain with this and allow readers to come to their own conclusions.

I hope to do more of my own research on this in the near future. My colleague Janet Love, author of a book on systemic work, alerted me to the writing of Professor Franz Ruppert, who has, I am told, written on this extensively.

I have witnessed/been part of somewhere between 80 and 100 constellations over the years. They are often very moving and healing, but I do not suggest they are a magical cure. Of all those I have seen, there were maybe three where the clients felt they did not get anything out of them (although very often the representatives did!). With regards to the long-term benefit, again I don’t think they offer a magical cure. However, I am always astounded when people tell me, years later, how moved they were by a constellation they had, or participated in (this feedback includes psychodynamic psychotherapists, existentialists and so forth). Moreover, people are telling me about aspects they hadn’t thought about at the time of the constellation but reflected on in the months and years after. With specific regards to our topic of loneliness, it seems to me that they often have profound and long-lasting benefit for client and representatives alike, due to the profound sharing and witnessing, quite apart from any other healing ‘surplus realities’.

Different constellators use systemic work for all sorts of questions, and I could write a lot about this. Thankfully, others have done so already, including Bert Hellinger, Franz Ruppert and Janet Love and there is a journal called The Knowing Field.

Loneliness seems like a massive cyclical problem for society – the alienating effects of vast impersonal communities, technological distancing, family breakdowns etc can tend to increase isolation and loneliness, which then causes further social, health and economic problems. Is that right?

Yes, of course we don’t want to make it look as if loneliness had never existed before, but the way you put it is very clear. It seems to have changed from a mainly ‘personal’ problem to one affecting our western societies on a much grander, systemic scale.

I gather there is an increase in the number of people who regard themselves as asexual, as happy loners, and who prefer to live alone. Do you think there are genuinely resilient loners out there as opposed to people who are more vulnerable to the negative effects of being reluctantly alone?

Absolutely, yes. Among others, Anthony Storr wrote about this beautifully in his book Solitude and, more clinically, in The Art of Therapy. In the former, he argued that ‘creative types’ as well as people with a project (researchers, scholars etc) might be more focused on their inner world, or work so that relationships appear less important. In the latter, he suggests that ‘schizoid types’ make good spies, as they don’t form such close attachments to others who would be endangered by their work.

In my own family, I observed how differently my two grandmothers reacted to the death of their respective husbands. One, extraverted by nature, found it extremely difficult to be alone. She became restless, like a caged animal, depressed and at times irritable, whereas the other one, who was more introverted and had always loved the arts and reading, was much more able to occupy her time meaningfully and remain positive. She outlived my grandfather by over 20 years.

The archetype of the hermit often craves being alone. However, I feel that we ought to be mindful as therapists that some people have adopted this as part of their persona out of need and end up dissociating a lot, perhaps even suicidal. It can be easy to forget that, as biological creatures, we are still herd animals and may thus be suppressing our needs for meaningful relationships. Just think of the delusion that, by carrying a mobile at all times these days, we like to think we are never alone.

Finally, as you say, we are witnessing more ‘asexual types’. Among others, David Deida has drawn attention to the fact that this group would be less interested in being in relationships yet, as I said above, I feel strongly that we need to be discerning as therapists as to whether this is a (mal)-adaptation or a person’s ‘soul nature’.

To what extent does your transpersonal therapy position and practice influence your views here? What roles do you see for non-transpersonal therapies?

The term transpersonal, on the most basic level, means ‘beyond the personal’. I have no requirement that my clients should be interested in this, or in any spiritual path. However, the very fact that we as transpersonal practitioners hold this dimension and trust in the connections between the individual and the collective/universe, whether this is made explicit or not, should make a difference to the field. There is for me a ‘holding the hope’ interest in the meaning of being with oneself and self-actualisation, rather than just ‘re-experiencing’ loneliness. The first time I scheduled my workshop ‘Loneliness and how to survive it’, my former course director at the Centre for Counselling and Psychotherapy Education Dr Nigel Hamilton laughed, ‘You are always alone!’ I retorted in true Jungian fashion, ‘You are never alone!’ I guess we believe both statements to be equally true simultaneously on different planes. What I like about the transpersonal as a framework is that it holds paradoxes.

I do feel that clients pick this up on some level, which might make it easier for them to bring up the problem of long-standing loneliness and isolation. Sculpting and constellation work are very specific ways of working and perhaps not exclusive to the transpersonal and vice versa.

What roles do I see for non-transpersonal therapies? Well, I feel they all have their own strengths and contributions to make. Research seems to show that the most important aspect in therapy is the quality of the relationship between client and therapist – and I think I have shown how important being witnessed and forming a secure attachment is for clients struggling with loneliness. Perhaps my two wishes would be that we as practitioners, from all backgrounds, look more at our own relationship to loneliness with our therapists and friends, so that we become increasingly more sensitive to the ways our clients talk about their loneliness, as well as becoming more able to hold this immense pain.

After all, it is an existential problem. Perhaps we also sometimes need to consider whether it would be in the clients’ best interest to make a referral to a group or a constellation workshop, but I don’t feel there is a need for ‘magical cures’ – just awareness. Making the transition from feeling lonely frequently to – at least sometimes – experiencing being at ease with oneself in being alone is profound work.

Madeleine Böcker, MA, Dipl Psych, MBACP, is an accredited transpersonal psychotherapist. She worked in a private psychiatric hospital in York for six years, and has been working in private practice for eight years in Maida Vale, West London, as well as running group workshops. Madeleine has a strong background in research and has been working for a number of years on the connection between loneliness and depression. She also works systemically and has an interest in Jungian Alchemy. For further information, please visit: www.psychotherapywithheartandsoul.org.uk