With many years’ experience of counselling in primary care I was looking for a challenge that would bring me the opportunity to transfer my skills to a new setting and learn about working with a different group of clients. An awareness of changes taking place in universities, where I worked as a teacher and researcher, stimulated my interest in working with young people making their way through higher education.

Students in this rapidly expanded sector are trying to gain degrees with limited financial support, frequently combining their studies with demanding part-time jobs. Many now come from families with no experience of university education. They are taught by staff trying to meet a vast increase in demand with no matching increase in resources. I believe that these pressures are linked with the development of psychological difficulties in the student population, which match the range and complexity of those experienced by primary care patients.

I was fortunate, then, to find additional, sessional work with the Brunel University Counselling Service.

During the wait for completion of my CRB check, I looked forward to the opportunity to continue developing my interest in the application of attachment theory to clinical work in a new environment. As a primary care counsellor I had carried out research into the mental and physical health effects of insecure attachment on bereaved adults1 and the university seemed to provide an environment rich in possibilities for anyone with an interest in attachment issues. Students are experiencing a period of rapid transition: they are leaving home and preparing for entry into the adult world through their work and studies. Their ability to negotiate this is dependent on a capacity to form healthy attachments with their peers and university staff, which has a significant effect on their eventual academic success or failure. This process takes place in a clearly defined community under the management of adults with attachment histories of their own.

Theory and research

John Bowlby2, the pioneer of attachment theory, defined the concept of attachment as a relationship between an attached person and an attachment figure, in which the former seeks security from the latter under stressful or dangerous circumstances. In Western culture the attachment relationship usually begins between a child and its parents, with the mother as the preferred or primary attachment figure. Bowlby proposed that the individual’s psychological organisation or ‘attachment system’ is designed to control those behaviours which will enable her/him to gain and maintain closeness to the attachment figure. Once closeness has been achieved, the attached person experiences a state of physiological equilibrium and a feeling of internal security, which is the goal of all attachment behaviour. Provided s/he knows the attachment figure is available and responsive, the attached person may not even need to stay physically close in order to feel safe. Attachment behaviour is most marked in early childhood, but will emerge throughout the life cycle, when the individual experiences stress, such as separation or loss.

Development of secure and insecure attachments

The individual’s attachment system continually monitors her/his surroundings and the attachment figure to work out whether it is safe outside and the attachment figure is available. If the environment is seen as non-threatening, the need for closeness to the attachment figure decreases and s/he may then act as a secure base from which the attached person can explore. Increased danger within the environment activates the pull towards the attachment figure. Secure attachment occurs in a caregiver/infant couple where the attachment figure is perceived as readily available and the infant only seeks closeness when outside danger increases.

Secure attachment leaves her/him free to explore the environment when no danger is present. Insecure attachment occurs in a dyad where the caregiver is seen as less available and can take on various forms. For example, an infant with an anxious form of attachment may see her/his caregiver as inconsistent or preoccupied. Consequently, s/he sets staying close as her/his primary goal and opportunities for exploring decrease, even when no danger is present.

Assessing attachment

Secure and insecure attachment may be assessed in infants using a laboratory procedure known as the Strange Situation, developed by Mary Ainsworth3. The procedure involves the observation through a one-way mirror of an infant, her/his mother and a stranger in an experimental room. Assessors are asked to observe eight episodes of separation and reunion between the mother and child and to record the infant’s interaction with the mother and the stranger. They are also asked to pay special attention to the infant’s capacity for exploratory play during the episodes. Recorded observations are used to assign the infant to one of the following categories: securely attached; insecure/avoidant; insecure/resistant; disorganised.

Hazan and Shaver4,5 developed a method of assessing security of attachment in adults, based on the categories derived from the Strange Situation, through an examination of the romantic couple relationship. In the romantic relationship each partner acts as the attachment figure for the other. The goal of attachment behaviour is the same as that in the infant/caregiver relationship; to stay close in order to feel safe and protected. Likewise the adult attachment system is primed to monitor the safety of the outside world and the availability of the attachment figure. Like the infant, the adult achieves equilibrium when s/he knows the attachment figure is close and accessible. The adult’s need for closeness increases when experiences such as illness, injury and emotional distress result in a feeling of insecurity. While the infant uses the caregiver as a secure base for exploratory play, the adult uses her/his partner in order to engage in creative activities such as work, study, sport and creative endeavour. Hazan and Shaver identified three patterns of attachment in adults: secure, anxious-ambivalent and avoidant. Secure individuals believe their partner is available and only use attachment behaviour when in need of support. Anxious-ambivalent individuals fear abandonment and tend to seek closeness to their partner even when little or no threat is present. Avoidant individuals mistrust others and tend to maintain emotional distance under stress.

Attachment and healthcare

Hazan and Shaver’s categories have been adopted by researchers interested in the links between attachment and how people use healthcare. Insecure attachment has been linked with patients’ varying responses to illness in terms of their capacity to elicit and use help from healthcare professionals. Hunter and Maunder6 described the illness behaviour typically associated with each attachment category and suggested how professionals might respond appropriately. Secure individuals are able to provide their carers with accurate information about their illness and use help and support most effectively. Anxiously attached individuals tend towards compulsive careseeking which can induce clinginess. Hunter and Maunder stress the need for a calm response on the part of the carer, coupled with setting clear boundaries. In this way, carers can anticipate anxiously attached patients’ need for closeness without devaluing it or being drawn in. They alert carers to the possibility of experiencing avoidant individuals as rejecting or non-compliant. Carers are advised to respond positively to their need for control of their treatment, while helping them to understand some of the emotions concealed by the need for autonomy.

Thompson and Ciechanowski7 have elaborated on this scheme to model ways in which carers’ attachment style can affect the quality of care they offer. Secure carers are able to identify the underlying emotional needs of their patients, whatever their attachment style, and respond flexibly. Their insecurely attached counterparts are more likely to focus on patients’ overt expressions of need. Avoidant carers tend to feel uncomfortable and withdraw, while the anxiously attached can become overinvolved. I suggest this attachment-based model of behaviour in patients and carers could provide a template for examining relationships between students and staff in educational settings.

Some research findings

College students provide universitybased psychology researchers with access to a convenient source of participants. Consequently, there is a substantial body of research into the links between quality of attachment and a wide range of psycho-social issues within this group. A search of the PsycINFO database revealed attachment-related investigations of depression8,9; anxiety and stress9; self-criticism8,11; selfworth11; social-functioning11-14; reluctance to become an adult14; drink and drug abuse15,16; romantic relationships17-19; ability to access social support20,21; immigration22; sexual experience and safe sex experience23,24; suicidal ideation25; schizotypy26 and psychotic phenomena and trauma12 and attachment; family background10,27,28 and past relationships12,29; social and psychological functioning30. However, few, if any of these studies focus directly on how students’ attachments influence their experience of university life and its outcomes. I was especially interested, then, by Toni Wright’s31 article on attachment and a postgraduate student’s academic journey, which highlights the influence of attachment style on the all-important relationship with the supervisor and its impact on the successful progression in doctoral studies. Further studies of the student experience, viewed from an attachment perspective, could provide researchers with a useful methodology, as well as producing further insights into the student’s capacity to operate effectively within her/his relationship network.

The student’s relationship network

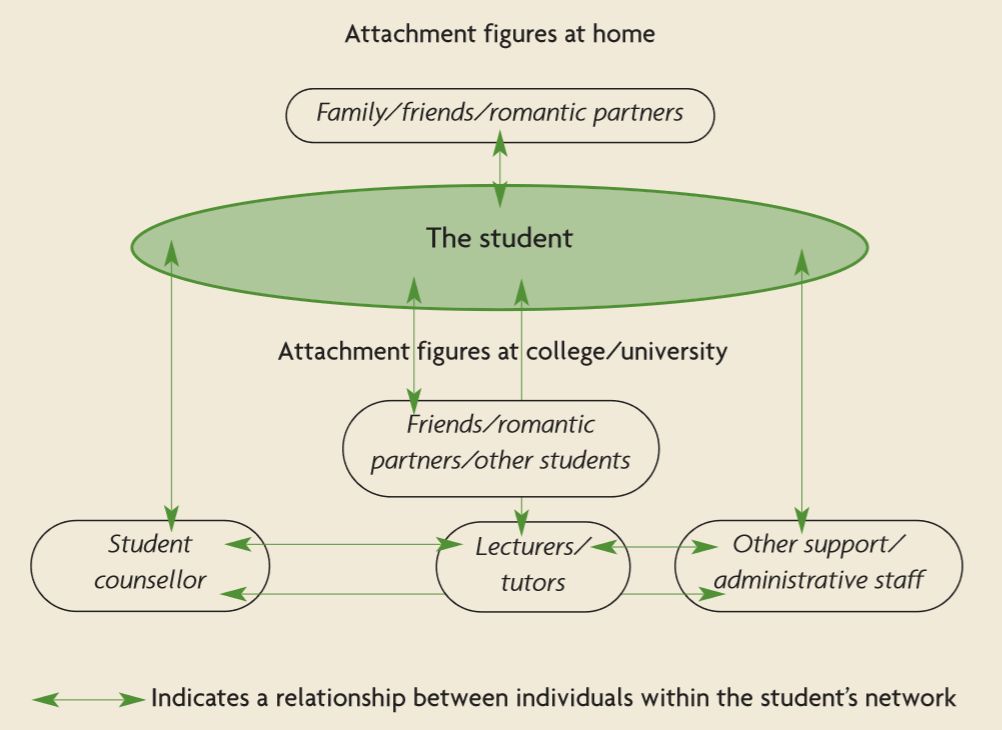

Every student exists within a network of attachment relationships (see figure 1), each of which will be more or less important at different points along the academic journey. The student will start her/his studies as a securely or insecurely attached individual, depending on her/his experience of earlier family relationships. Her/his quality of attachment will exert a powerful influence on the capacity to form successful relationships with other students and with staff; especially in times of stress as it affects her/his ability to seek and use help. This can have a major effect on performance and the student’s overall experience of college or university life. It is also worth remembering that each person involved in the student’s academic experience also exists within the centre of their own relationship network, and their capacity to respond to the student will be affected by their own quality of attachment.

Figure 1: The student's relationship network

The application of an attachment-based model

Understanding attachments can provide valuable insights for anyone who works or conducts research with students. The attachment-based model of healthcare described above can be usefully adapted by student counsellors, especially when faced with a range of typical problems presented such as: homesickness, anxiety about a parent who is depressed, anxious or abusing alcohol; anxiety about marital difficulties in the parental relationship; forming maintaining and breaking romantic relationships outside or within the institution; problems with tutors and supervisors of theses and work placements; problems with friends and housemates. All these difficulties are likely to impact negatively on performance and will become particularly significant as exams and important deadlines loom. Many students approach the counselling service with academic concerns as their initial presentation, even if they are troubled by underlying difficulties.

Offering counselling from an attachment perspective

There is an essential difference between the two insecurely attached groups identified by Hazan and Shaver. Anxious-ambivalent individuals tend to draw closer to attachment figures under stress, while the avoidant tend to distance themselves. This is significant when thinking about which individuals are more likely to access the counselling service and how they might approach the counselling relationship.

There is some evidence that anxious-ambivalent individuals have the highest attendance rates within primary care32. If this trend is reflected in the student population, the counsellor needs to be attuned to the particular ways they present their difficulties. Very often these individuals are overwhelmed by their emotions and find it hard to express precisely what troubles them. With careful listening, the counsellor can help them identify core difficulties, rather than running on from one problem to the next, as if each were as important as the other. They may make a high level of investment in their therapy, but the counsellor can experience them as demanding, clingy or helpless. It is very important that the counsellor maintains clear boundaries and validates the need for closeness, without becoming over-involved, while helping these students understand that this is not rejection. As part of this process, students can be enabled to identify strengths, disengage from the victim position and recover their coping capacity.

When avoidant individuals access the service, they may focus on academic issues. They can be stern judges of their achievements and view satisfactory results as a failure, which reflects badly on the self. Their history often reveals that closeness to the parents was conditional on high levels of performance in school and in other arenas. Despite protestations that they were never pushed, they frequently come from families of high achievers with high expectations of each other. As Hunter and Maunder suggest, these individuals tend to respond positively to a collaborative approach, which leaves them feeling in control of the process with their independence intact. Under these conditions they will feel safe enough to become aware of needs they were reluctant to acknowledge or express, particularly the need to ask for help when in distress. In fact, one of the chief difficulties for this group is accessing counselling in the first place. The Brunel University Counselling Service has set up a bibliotherapy scheme with the library and runs a psycho-educational course, ‘Tools for Life’, which is likely to appeal to this group, as they can join in as active participants rather than as people in need. Not only will they benefit from this approach, but it can enable them to access the counselling service more easily when they need it in future.

With reference to Ciechanowski’s model, it is worth considering ways in which the counsellor’s personal attachment style might affect her/his response to client need over time, bearing in mind that the anxious-ambivalent counsellor has the potential to experience burnout if over-involved, while the avoidant is at risk of becoming ‘case-hardened’ and unable to attend with sensitivity.

How did an attachment perspective help me?

Although I have worked with many clients in primary care from diverse cultures, they tend to be settled in this country or belong to a second generation of immigrants who have grown up here. In adjusting to my new role as a student counsellor, I found an attachment perspective especially useful when working with international students, who are adjusting to an unfamiliar education system in a new country, far from home, while pursuing their studies in a foreign language. In formulating their difficulties and identifying a focus for counselling, it was helpful to reflect on the impact of a strange situation on this group in making sense of their experience.

Case 1

‘Tyra’, a Scandinavian student, believed she was at risk of failing her first-year studies. Following a relationship breakup she felt lonely and isolated and, as a result, was unable to concentrate on course work and exam revision. She had offered a lot of support with practical problems to a group of friends, which included her ex-partner, since she started university, and was beginning to feel exploited. She felt a heavy burden of family expectation which prevented her from letting her parents know the full extent of her difficulties. They had always made it clear that each child in the family was expected to gain a degree and go on to study at postgraduate level. Her background suggested the development of an avoidant pattern of attachment. Her need to give to others, while expecting little in return, was consistent with the avoidant individual’s tendency to attempt to satisfy her own needs by attending to others, which seems to have intensified under the stress of finding herself in an unfamiliar environment. We worked on helping her resume her academic studies as the goal of the counselling, an aim consistent with her values, which helped her invest in the counselling relationship. Much of the work, though, focused on how she could re-evaluate her role in relationships as a person worthy to be valued for herself, rather than one who is only valued for what she does for others. Thus, she was enabled to look at some of the underlying emotional issues, which drove the way in which she usually approached relationships, without feeling stripped of her autonomy, and regain her ability to concentrate and achieve good results.

Case 2

‘Tariq’ had fallen behind with his postgraduate degree and intended to apply for an extension of the time allowed for completion. He presented with multiple problems in his life, but in time we were able to identify two significant difficulties interfering with his academic progress: a breakdown in the relationship with his supervisor; and enormous responsibilities for his large family, which involved travelling frequently between England and India to sort out their problems. The confusing presentation of his difficulties, together with the preoccupation with relationships at home, which overwhelmed his capacity to engage with the demands of his studies, suggested an anxious-ambivalent pattern of attachment. His most pressing problem, in his view, was the risk of being excluded from the university and going home in disgrace. It emerged that Tariq had not made his supervisor aware of the nature of his problems at home because he found him cold and unsympathetic. So, working on the supervisory relationship seemed the most useful focus for our sessions. There seemed to be a cultural dimension to the relationship difficulty. In his home-country Tariq’s university teachers had taken a quasi-parental interest in his progress at undergraduate level, and when his supervisor did not meet his expectation of a similar degree of closeness during their initial meetings, he experienced it as rejection. We examined Tariq’s expectations of the supervisory relationship and considered how a more business like approach to it might help him to communicate more effectively. In trying out this new relational style, Tariq found that he was able to elicit the help he needed from his supervisor and make a successful application for an extension.

Conclusion

The material presented here should suggest how an attachment perspective can provide valuable insights into the links between clients’ personal history and their capacity to form the kind of relationships at college or university which are crucial to academic success. From my experience, knowledge of attachment issues enhanced my ability to work with a new group of clients by helping me formulate difficulties and identify goals consistent with their relational style, and, from their point of view, made sense of the counselling process.

Jane McChrystal is a student counsellor at Brunel University Counselling Service. She is also a counsellor in primary care and private practice and provides attachment-based training for counsellors and allied professionals.

References

1 McChrystal J. The psychological impact of bereavement on insecurely attached adults in a primary care setting. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2008; 8(4):231-238.

2 Bowlby J. Attachment. London: Pimlico; 1997.

3 Ainsworth M, Blehar M, Waters E, Walls S. Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978.

4 Hazan C, Shaver PR. Romantic love conceptualizes as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987; 52:511-524.

5 Hazan C, Shaver PR. Love and work: an attachment theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Psychology. 1990; 59:270-280.

6 Hunter JJ, Maunder RG. Using attachment theory to understand illness behaviour. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2001; 23:177-182.

7 Thompson D, Ciechanowski P. Attaching a new understanding to the patient-physician relationship in family practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Practitioners. 2003; 16(3):219-226.

8 Liu Q, Nagata T, Shono M, Kitamura T. The effects of adult attachment and life stress on daily depression: a sample of Japanese university students. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009; 65(7):639-652.

9 Gilbert P, McEwan K, Mitra R, Franks L, Richter A, Rockliff H. Feeling safe and content: a specific affect regulation system? Relationship to depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2008; 3(3):182-191.

10 Sibley CG, Overall NC. The boundaries between attachment and personality: Localized versus generalized effects in daily social interaction. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008; 42(6):1394-1407.

11 Berry K, Band R, Corcoran R, Barrowclough C, Wearden A. Attachment styles, earlier interpersonal relationships and schizotypy in a non-clinical sample. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2007; 80(4):563-576.

12 Yoshimura T, Hamaguchi Y. Structure and related variables of ‘reluctance to become an adult’ during adolescence. Japanese Journal of Counseling Science. 2007; 40(1):26-37.

13 Katz J, Nelson RA. Family experiences and self-criticism in college students: testing a model of family stress, past unfairness, and self-esteem. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2007; 35(5):447-457.

14 Berry K, Wearden A, Barrowclough C, Liversidge T. Attachment styles, interpersonal relationships and psychotic phenomena in a non-clinical student sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006; 41(4):707-718.

15 Kilmann PR, Carranza LV, Vendemia JMC. Recollections of parent characteristics and attachment patterns for college women of intact vs. non-intact families. Journal of Adolescence. 2006; 29(1):89-102.

16 Creasey G, Ladd A. Generalized and specific attachment representations: unique and Interactive roles in predicting conflict behaviors in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005; 31(8):1026-1038.

17 Hawkins-Rodgers Y, Cooper J, Page B. Nonviolent offenders and college students' attachment and social support behaviors: implications for counseling. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2005; 49(2):210-220.

18 van Ecke Y. Immigration from an attachment perspective. Social Behavior and Personality. 2005; 33(5):467-476.

19 Torquati JC, Raffaelli M. Daily experiences of emotions and social contexts of securely and insecurely attached young adults. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004; 19(6):740-758.

20 Park LE, Crocker J, Mickelson KD. Attachment styles and contingencies of self-worth. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004; 30(10):1243-1254.

21 Yamagishi A. The relations between present interpersonal frameworks and quality of past relationship with their mothers and friends described in life histories in female adolescents. Japanese Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2004; 15(2):195-206.

22 Gentzler AL, Kerns KA. Associations between insecure attachment and sexual experiences. Personal Relationships. 2004; 11(2):249-265.

23 Creasey G. Psychological distress in college-aged women: links with unresolved/preoccupied attachment status and the mediating role of negative mood regulation expectancies. Attachment & Human Development. 2002; 4(3):261-277.

24 Aspelmeier JE, Kerns KA. Love and school: attachment/exploration dynamics in college. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2003; 20(1):5-30.

25 Stackert, RA, Bursik, K. Why am I unsatisfied? Adult attachment style, gendered irrational relationship beliefs, and young adult romantic relationship satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003; 34(8):1419-1429.

26 McNally AM, Palfai TP, Levine RV, Moore BM. Attachment dimensions and drinking-related problems among young adults: the meditational role of coping motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2003; 28(6):1115-1127.

27 Kanemasa Y, Daibo I. Early adult attachment styles and social adjustment. Japanese Journal of Psychology. 2003; 74(5):466-473.

28 Strang SP, Orlofsky JL. Factors underlying suicidal ideation among college students: a test of Teicher and Jacobs’ model. Journal of Adolescence. 1990; 13(1):39-52.

29 Kenny ME, Donaldson GA. Contributions of parental attachment and family structure to the social and psychological functioning of first-year college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1991; 38(4):479-486.

30 Blain MD, Thompson JM, Whiffen VE. Attachment and perceived social support in late adolescence: the interaction between working models of self and others. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1993; 8(2):226-241.

31 Wright T. Attachment and the academic journey. AUCC. November 2009; 31-35.

32 Ciechanowski P, Walker E, Katon W, Russo J. Attachment theory: a model for health care utilization and somatization. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002; 64(4):660-667.