The controversial topic of pre-trial therapy (PTT) is in the news again, following a successful petition, supported by 13,000 people, against police access to clients’ counselling records and their use as critical evidence in criminal trials.1 The UK Government responded positively, promising a review of current guidelines and endorsing the value of therapy in supporting victims of rape and sexual assault.

All therapists need to develop a working knowledge of trauma and sexual abuse. However, the legal aspects of working with abuse victims and survivors in the form of pre-trial therapy can present some additional, possibly intimidating, features. So, what is PTT? The term applies when a counselling client is a potential witness in a criminal trial of their alleged abuser or abusers. PTT requires a certain level of specialist knowledge, training and experience, including an understanding of the justice system.

Agencies should have sound initial assessment criteria in place, in order to pick up cases likely to involve PTT at an early stage. They can thereby avoid making potentially inappropriate referrals to students, or to trainees on placement, who may lack the required knowledge or skills.

It’s important to recognise that PTT is different to generic therapy. The key differences include the need for an explicit but flexible contract on the focus of therapy, provision for information-sharing with the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), the nature and potential uses of record-keeping, and the therapy’s overall relationship to the trial process.

The CPS, together with the Home Office and the Department of Health, issues detailed (though nonstatutory) practice guidance on PTT. It has been in place for almost 20 years in England and Wales and brings an added and powerful legal dimension to the already challenging work of providing therapy for the victims and survivors of sexual abuse.

There are two sets of legal guidance: one for working with clients who are under 18 years old2 and one for adults deemed to be vulnerable or intimidated witnesses.3 We address in this article practice issues related to the latter client group, although much of the material will also apply to PTT with children and young people.

A witness is defined as vulnerable if the court considers that the quality of their evidence will be reduced on the grounds of suffering from a mental disorder under the Mental Health Act 1983, or from a physical disability. Similarly, a witness might be deemed intimidated if their evidence will be diminished by their fear or distress in testifying. In practice, these definitions are interpreted and applied by the courts to any client who has experienced sexual violence. The term ‘vulnerable adult’ is, therefore, an operational definition, applied by the courts to all victims of sexual violence. It does not depend on an assessment of the individual client’s level of vulnerability or resilience.

It’s worth bearing in mind that almost any therapy carries the potential to become involved in a criminal trial. For example, a client might disclose past sexual abuse in therapy and decide to pursue a criminal case long after the therapy has ended. Given this level of unpredictability, all generic counsellors need to have some basic familiarity with the CPS practice guidance.

The practice guidance explicitly states that the counsellor and client should avoid ‘exploring in detail the substance of specific allegations made’.3 It also calls for close liaison between the therapist, the client and the CPS, with the clear understanding and the explicit consent of the client.

Other key aspects of the guidance are:

- the CPS should be informed of any PTT taking place

- PTT should begin after the client has given their statement of evidence to the police

- detailed factual records of therapy should be kept and made available to the CPS as required

- PTT should focus on the client’s current responses and coping, rather than on the original abuse

- certain types of therapy are preferred as supporting this kind of ‘current’ focus

- the PTT needs to focus on the welfare of the client, rather than simply on the pending court case.4

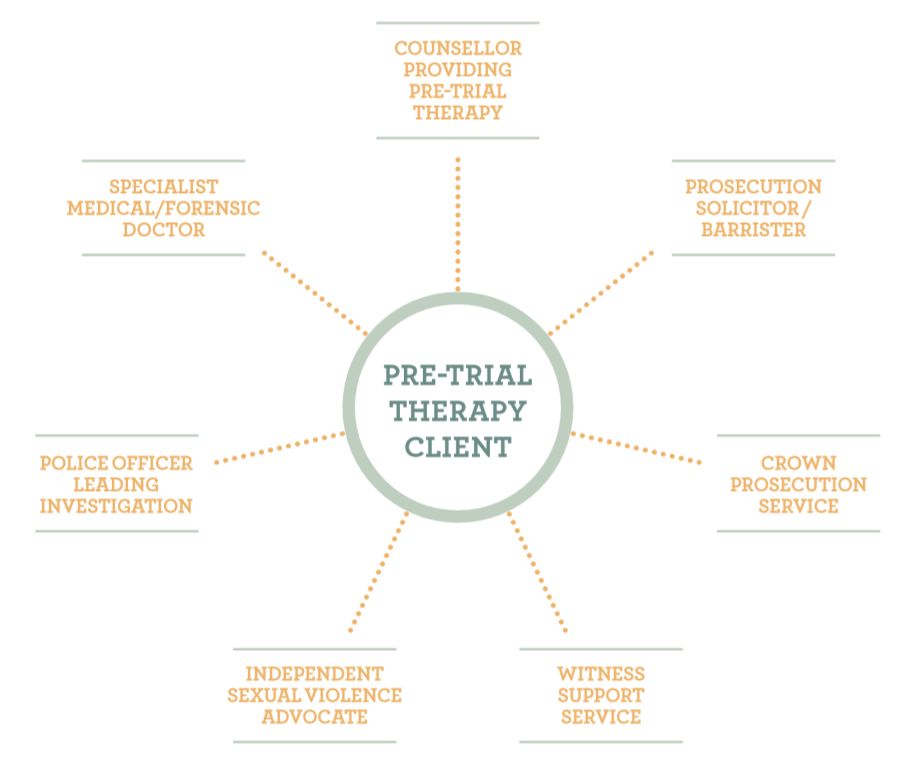

The PTT counsellor becomes a member of a much wider team of professionals, built around the client, including the police, CPS, lawyers and medical practitioners. PTT counsellors might never meet any of the other team members, but their work is available to the CPS in the form of therapy records. The counsellor is therefore a crucial member of the team, with potentially significant implications for the progress and outcome of the criminal trial (see diagram below).

The pre-trial therapy counsellor as a ‘virtual’ member of the multidisciplinary team of professionals supporting the client.

The counsellor’s records can play an important supporting role as evidence in the forthcoming criminal trial and will almost certainly be summoned by the court. Records of therapy can include video and audio formats, as well as written notes. Records are set in a quasi-medical, or police, evidential model. They ‘should include, in the case of therapy, details of persons present and the content and length of the therapy sessions’.3 However, the CPS does not require verbatim or transcript-type records of therapy.

In addition, counsellors can be called as witnesses in a court case. They might be asked to clarify specific aspects of their therapeutic practice, or to amplify the meaning of their records, sometimes under hostile cross-examination. BACP guidance advises that: ‘Notes kept of therapy sessions should be concise, accurate and reliable in evidence.’5 Working within the guidance thus adds another dimension to therapy; it is no longer a private, confidential transaction between client and therapist. BACP good practice correspondingly points to the need for clear contracting regarding information-sharing of therapy records.5

There is an anxiety in legal circles that PTT can inadvertently undermine the witness evidence. Evidential damage takes two main forms: either contamination or coaching. In the case of contamination, the concern is that the client’s own recollections of sexual assault might be influenced by the therapist’s use of inappropriate or leading questions, or through exposure to the experiences of other clients, such as in group therapy.

Some agencies share the anxiety about contamination and are convinced that PTT should not be offered to clients in case it compromises the evidence against their alleged abusers, causing the trial to collapse.

The unease about coaching is that there may be the opportunity in therapy for a client to rehearse the answers to questions later asked in court. Clearly, therapists need to be mindful of the legal context and implications of their work. However, it is revealing that the metaphor of contamination suggests a fear that counselling has a somewhat toxic quality and needs to be carefully handled in order to avoid infecting an otherwise robust and healthy legal process.

Therapists often have their own concerns about PTT. Some worry that it’s almost impossible to avoid revisiting the client’s experience of abuse in some way, which could imperil the court process. For others, PTT might conflict with their own values, by seeming to limit client choice, or by postponing more intensive therapy until after the trial.

The uncertainty surrounding PTT is increased by the lack of a central register of suitably qualified therapists. There is, by contrast, a register for court intermediaries, who support clients with disability throughout the trial process. Some training for therapists is available, often in the form of day workshops provided by specialist agencies. But there is no accreditation of recognised training for pre-trial therapists, unlike the training for the separate, non-therapeutic role carried out by independent sexual violence advisers (ISVAs).

Research and commentary on PTT are still fairly limited,4,6 although one of the authors of this article, who has also worked in an agency that deals with clients who have been sexually assaulted in childhood, has recently produced a qualitative piece of research.7 The research explores the experience of therapists in providing PTT for adult clients and how they managed some of the dilemmas and issues involved in PTT. Of the six therapists recruited, five worked within an agency setting, five were female, and one was male. All were of white British ethnicity and their ages ranged between 45 and 65 years. Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted and analysed, using interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA). The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Chester and was conducted in accordance with BACP’s Ethical Framework8 and Chester University’s Research Governance Handbook.9

The research highlighted three broad themes: the differences that therapists experienced between providing generic therapy and PTT; the complexity of PTT and the corresponding level of competence required; and the conflicts and dilemmas that PTT can present to counsellors. What was striking about the research findings was the extent of common ground. For example, all of the participants identified good supervision as important in helping them to cope personally and professionally with the challenges of PTT. They also talked about the intensely emotional impact of the work, which often provoked powerful feelings of anger, frustration and sadness.

All the therapists believed that PTT was beneficial to their clients. For example, Beth (all names have been changed to protect confidentiality) said: ‘To actually see her bloom, it was beautiful.’ Janet found herself mirroring her client’s positive feelings about therapy. So, when the client was empowered, Janet also felt herself become energised by the work. Participants expressed the view that therapy was a way of strengthening their clients, by helping them to manage the feelings attached to their trauma.

Some of the participants in the study reported feeling reassured by strong backing from their agency in helping them negotiate the legal complexities of PTT. One participant, Cathy, said: ‘I’m just so grateful that my experience of pre-trial therapy is being in an organisation that specialises in it and therefore where we have drummed into us the whole thing about the CPS guidelines.’ Similarly, Beth talked about the benefits of belonging to an agency as a way of being part of a support network, explaining that ‘…we have what’s called an area lead, so that if I see a client I have concerns for, I can raise that straight away’.

The research explored possible tensions between certain modalities of counselling, such as the person-centred approach (PCA) or eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), and the specific requirements of PTT. The potential conflict between the need to follow the CPS guidance and the client’s own preferences and autonomy was highlighted by four of the PCA therapists. For example, Cathy said: ‘If it happened that I had a client with whom I was working pre trial, who really wanted to talk about what had happened, then I would have a bit of a conflict, because of the way that I choose to work, which is in a very person-centred way and which is giving, as a client, the choice about what we talk about’. In contrast, Rachel welcomed the CPS guidelines: ‘I feel what the pre-trial therapy guidance gives me is a framework in which to operate as a person-centred therapist.’

All of the therapists in the study were fully aware that their notes could be subpoenaed by the court, but there were different approaches to client notes. Rachel showed the client the notes in the following session. James, who used EMDR as the primary intervention with the client, wrote two sets of notes: a summary and a more comprehensive account of the session. With his client’s consent, James gave all his notes to the CPS. ‘We agreed that I would work completely transparently and openly with the CPS. I gave them the lot.’

It is clear from the research that PTT presents clients and therapists with a number of challenges, particularly the need to clarify the focus of therapy and maintain appropriate session records in order to avoid undermining the client’s evidence. But it can also offer real benefits to clients, supporting them through the process of recovery from sexual trauma.

The research also shows that CPS practice guidance provides a context and framework for counselling in this specialist field. However, since the guidance was issued, there have been significant developments in psychotherapeutic practice as new techniques and modalities have emerged. For example, EMDR is an evidence-based treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which helps clients to process trauma memories, ideally enabling them to provide a more accurate and comprehensive account of the incident. EMDR involves very little verbal input from the therapist, and the client does not need to talk in detail about the trauma to heal. The risk of a therapist ‘coaching’ a client is therefore low. The guidance requires updating to take account of such developments in trauma therapy, in order to provide evidence-based therapeutic support to victims and survivors of sexual violence who are going through the court process. A review of the current CPS guidelines could also provide clarity for counsellors about the types of therapy that can be offered and help address some of the ethical questions raised by pre-trial therapy.

A summary of the research findings exploring the experience of therapists in providing PTT for adult clients is available on request.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Dr Nikki Kiyimba, Senior Lecturer in Psychological Trauma at the University of Chester, for supervising Maddie Nixon’s MSc dissertation.

Peter Jenkins is a counsellor, supervisor, researcher and trainer, with a long-standing interest in pre-trial therapy.

Maddie Nixon is an integrative psychotherapist, supervisor and EMDR practitioner. She has a private practice and specialises in trauma therapy. Maddie also offers training in pre-trial therapy.

Resources

BACP. GPiA 070 Legal Resource: Working with CPS guidance on pre-trial therapy with adults in the counselling professions. (Content Editor Mitchels B). Lutterworth: BACP; 2018.

References

1 Petitions. UK Government and Parliament. Stop counselling notes of rape survivors being used in court. [Online.] London: Petitions. UK Government and Parliament; https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/245103/ (accessed 14 October 2019).

2 Crown Prosecution Service/Department of Health/Home Office. Provision of therapy for child witnesses prior to a criminal trial: Bolton: CPS; 2001. https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/therapy-provision-therapy-child-witnesses-prior-criminal-trial .

3 Crown Prosecution Service/Department of Health/Home Office. Therapy: provision of therapy for vulnerable or intimidated adult witnesses. London: Home Office Communications Directorate; 2002. https://www.cps.gov.uk/ legal-guidance/therapy-provision-therapy-vulnerable-or-intimidatedadult-witnesses.

4 Jenkins P, Muccio J, Paris N. Pre-trial therapy: avoiding the pitfalls. Healthcare Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal 2015; 15(2): 8–11.

5 BACP. GPiA 070 Legal Resource: Working with CPS guidance on pre-trial therapy with adults in the counselling professions. (Content Editor Mitchels B). Lutterworth: BACP; 2018.

6 Jenkins P. Pre-trial therapy. Therapy Today 2013; 24(4): 15–17.

7 Nixon MA. A qualitative exploration of therapists’ experience of working therapeutically pre-trial within the Crown Prosecution Service guidelines with adult clients who have reported sexual violence. MSc dissertation [unpublished]. Chester: University of Chester; 2019.

8 BACP. Ethical framework for the counselling professions. Lutterworth: BACP; 2018.

9 University of Chester. Research governance handbook. Chester. 2014.