Think about a time recently when you felt happy. Who were you with? What were you doing? How did you know that you felt happy?

This is the first exercise that we ask IAPT staff to complete when they participate in our ‘Happy Hour’ programme. We ask participants to pair up and talk to each other about the above questions. It is a simple exercise that has a significant positive effect. Immediately you see people lean in, smile, laugh and connect. When we regroup, we hear that people generally talked about spending time with family and friends or engaging in a satisfying hobby, appreciating the little things and feeling a sense of achievement. We know that we feel happy when we experience positive emotions such as enjoyment, love, excitement, contentment and peace. We also know that sharing these feelings with others makes us happier and that being happy is important to us.

Finally we ask Happy Hour participants why they think we ask them to engage in this exercise, other than to break the ice. It doesn’t take a genius to realise that talking about happy times instantly makes us feel happier or that seeing someone smile makes us smile too. However, it might surprise you to learn that the exercise is based on a real phenomenon known as the ‘Happiness Advantage’.1 This phenomenon gives you and your brain a competitive edge because, when you experience positive emotions, your brain chemistry changes significantly. Positivity boosters, such as dopamine, not only make you feel brighter, they also open up the learning centres of the brain, allowing you to be more flexible and creative in your thinking; they also enhance your ability to memorise information. So the first exercise in the Happy Hour not only ensures that participants will enjoy the session and evaluate it more positively, it also ensures they will retain more of the information due to a boost in their working memory.1

The Happy Hour project was undertaken by myself and colleagues from an IAPT service in north-west England between 2014 and 2016. It was aimed at staff working as counsellors, psychological wellbeing practitioners and CBT therapists. The purpose of the initiative was to increase awareness of the science of happiness within psychological therapies, to offer a supplementary treatment option to enhance wellbeing alongside traditional talking therapies, and to improve staff wellbeing, in order to create happier teams.

Although we talk about subjective wellbeing within IAPT services, little reference is made to the concept of happiness. This may be due to the term itself being viewed as too ‘fluffy’ or vague, without clinical significance. However, the emergence of a new field of psychology, known as positive psychology, is repackaging and redefining the ‘H’ word and informing us of its potential value in work and health.

Psychology over the last 60 years has been predominantly concerned with pathology and mental ill health,2,3 with talking therapies particularly focusing on alleviating and reducing disease and suffering. Although the aim of interventions such as counselling and CBT is to bring about improved health and wellbeing, very little attention has been dedicated to the implementation of and training in positive practices that would enhance wellbeing and emotional health. Instead, the approach has been focused on the reduction of negative symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, as a way of bringing about relief. The emerging field of positive psychology argues that this approach is not nearly good enough.3 As Harvard psychologist, Shawn Achor, suggests: ‘You can eliminate depression without making someone happy. You can cure anxiety without teaching someone optimism. You can return someone to work without improving their job performance.

If all you strive for is diminishing the bad, you’ll only attain the average and you’ll miss out entirely on the opportunity to exceed the average.’1

This observation not only applies to those receiving treatment, but also to therapists themselves. Ironically, there has been very little emphasis on the wellbeing, resilience and happiness of IAPT staff, despite recent reports highlighting growing unhappiness and a need for change.5

Positive psychology is an umbrella term for the study of optimal human functioning; it is the study of positive emotions, positive character traits, resilience, talent, wisdom, altruism, health and happiness. Findings from this new area of research are intended to enhance rather than replace what we already know about the human condition from traditional psychology, thus providing a more balanced and holistic psychological perspective.3

So what does happiness mean and why should we pay more attention to it? Happiness enables flourishing and it enables health and being healthy. It is not just about experiencing pleasure and good cheer, but is also about an optimal way of being.6 Happiness means that we experience frequent positive emotions such as joy, peace and contentment, combined with deeper feelings of meaning and purpose. It implies a positive mood right here in the present and a positive outlook for the future.6

The science of happiness has discovered that happiness comes more naturally for some people than for others. Recent studies have revealed that we all have a genetically determined ‘set point’, which we inherit from our biological parents. These studies found that 50 per cent of our capacity for happiness comes from our genes, giving us all a baseline or potential for happiness that we return to, whether we win the lottery or suffer a loss.7

Surprisingly, our circumstances account for very little, so factors such as whether you are married or single, how much money you earn, what kind of car you drive and how attractive you are, only account for a 10 per cent variance in your capacity for happiness.8 Whenever I introduce this idea to people, they always seem quite shocked, and perhaps rightly so. It seems almost counterintuitive in our time and culture, when we are often confused in our quest for fulfilment and tend to look outside of ourselves for our happiness, lamenting, ‘If I could only have this or if only this were different, then I would be happier’. However, changes in circumstances only bring transient changes in our levels of happiness; once we have become habituated to them, they have very little effect on our overall wellbeing.8

Yet this is not the whole story. There is some good news: a very uplifting 40 per cent of our happiness level is within our control. Although our genes play a significant part and our circumstances contribute somewhat, the remaining 40 per cent of the pie relates to our own actions.8 This is where the science of happiness comes into its own, as it discovers ways in which we can adopt new behaviours and habits that will boost our potential and increase our overall baseline of happiness.

Over the past 10 years there has been growing evidence that demonstrates the tangible benefits of leading a happier life. Large studies conducted across different countries and cultures have shown a significant association between happiness and health.9 In particular, studies have found that happy people report lower incidents of ill health and greater psychological health and resilience, including lower incidents of stress, pain, cardiovascular disease and obesity.9–11 Studies have also found a link between happiness and longevity, with happier people on average living longer than less happy individuals.9,12

From a business and organisational perspective, there is substantial evidence for cultivating a happier workforce, not least because happier employees will be healthier and will require fewer days off sick. Studies suggest that happy people are more productive, motivated and compassionate, which brings us back to happiness within an IAPT workforce and the need for a change in culture.1,13

The Happiness Project within our service has been a vehicle for change, as it has highlighted the need for positivity in an often highly negative and serious environment. Initially we delivered the Happy Hour, which was a one-hour workshop for both staff and patients, consisting of a presentation with some music and video clips. The session was so popular that we were encouraged to develop it further into a two-hour interactive workshop, which we now call the Habits of Happiness workshop. This continues to run with Lancashire Care Trust’s Preston and Chorley Mindsmatter teams, and I am developing it further in my current role as a lecturer working at the University of Central Lancashire.

The aim of the workshop is to help participants to understand what determines happiness and to introduce them to theories from the science of happiness. These include the seven habits of happy people, namely, investing in relationships, caring for others, exercise, ‘flow’ (a joyous state of absorption), character strengths, spiritual engagement and cultivating a positive mindset, specifically gratitude, optimism and mindfulness.6,14 Participants are encouraged to discuss ways of incorporating these habits into their daily home and work lives and are provided with Action for Happiness booklets 15 to help them to record their journey. One of the simplest interventions introduced in the workshop is the ‘three good things’ exercise.16 This is an evidence based exercise that asks people to make a note of three good things that have happened to them during the day, such as having a coffee with a friend, completing a task or enjoying a beautiful view. They are also encouraged to give an explanation as to why this particular thing was good or made them feel happy. If practised daily for two weeks, this exercise has been found to increase happiness for up to six months afterwards.16

Finally we introduce the concepts of fun, playfulness and laughter, and how vital it is to seek out the lighter side of life. Stuart Brown, the founder of the National Institute for Play, advises that: ‘Remembering what play is all about and making it part of our daily lives is probably the most important factor in being a fulfilled human being.’17 This was one of the areas in which we discovered the most resistance within the culture of the organisation, not because people don’t want to have fun or be playful, but because staff often feel the need to seek permission for it and are afraid of how it would be interpreted. The question arises: ‘If you’re having fun at work, does that mean you’re not being professional?’ Some participants also worried that they had forgotten how to be playful and said that they rarely laughed at work. Again, we take a scientific approach to explaining the benefits of cultivating childlike playfulness; these include reduced stress, increased endorphins that boost wellbeing and help manage pain, increased immune defences and enhanced mental functioning.17–20

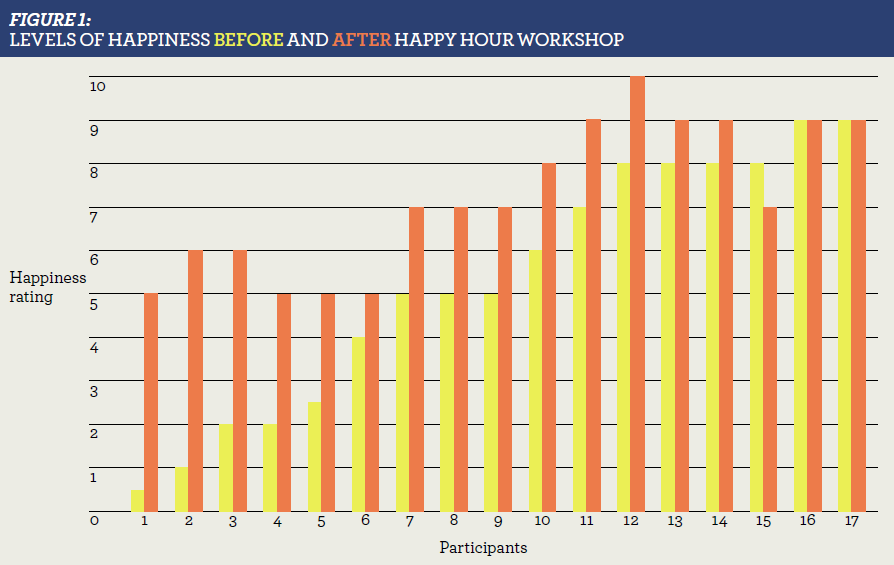

Although we introduced staff to interventions that they could use for themselves and for clients, the session itself became an intervention and we were asked to deliver it across the trust and to the wider community. In order to evaluate the impact, we asked staff members to complete some rating scales and a feedback sheet. Likert scales for happiness, fun and optimism were used to explore changes in mood and attitude. We asked participants to complete an initial rating before the session started and a further one at the end of the session, in order to see if the workshop had an impact on their subjective mood. Participants were asked to rate their mood, using a scale of 1–10, with 1 representing not happy at all and 10 representing very happy.

The graph shows the subjective happiness ratings of 17 participants before the session (in yellow) and after the session (in orange). It shows that the individuals who reported the lowest levels of happiness at the beginning showed the greatest increase in their levels of happiness at the end of the session.

The graph shows that 14 people rated their happiness as higher after the session, two rated it as the same (9/10) and one person rated it as lower after the session. On average, participants rated themselves as 36 per cent happier following the session, with 20 per cent reporting an increase of 150 per cent or more. Similarly, attendees reported an average 31 per cent increase in the likelihood of them seeking out opportunities for fun and laughter after the session and an average increase of 28 per cent in optimism. Following participation in the sessions, participants reported feeling ‘lighter’, ‘more positive’ and ‘uplifted’.

We are encouraged by these preliminary findings and are planning to conduct a formal study of Happy Hour in Mindsmatter service next year. The targets and high-volume work demands of being a therapist in IAPT mean that it is very easy to focus purely on the pressure and dissatisfaction. However, it is precisely because of these demands that we need to take a wider perspective. As staff sickness, absenteeism and burnout are more widely reported, we need to seek novel ways to nurture and cultivate job satisfaction, compassion, optimism and happiness. As facilitators of psychological wellbeing, our own wellbeing needs to be a priority. We therefore need to move beyond just the reduction of stress and the absence of illness to a more positive future, where the happiness of the workforce is incorporated into service design, enabling higher levels of health and wellbeing for all individuals and a thriving, happier community.

Lowri Dowthwaite works as Lecturer in Psychological Interventions at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan), teaching mainly on the IAPT Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP) Programme. Prior to working at the university, Lowri worked as a Senior PWP within Lancashire’s Mindsmatter service. Lowri has an MSc in Clinical Psychology and runs a number of happiness and positive psychology workshops at the university. She has also recently trained as a laughter yoga facilitator and is setting up a laughter club at UCLan.

The author would like to thank Angela West (counsellor at Mindsmatter) and Catherine Morton (PWP) for all their encouragement and support.

More from Healthcare Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal

A troubled legacy: the challenges of counselling in Northern Ireland

Open article: Jane Simms and Michael McGibbon examine service provider experiences of community and voluntary-based counselling provision in Northern Ireland. Healthcare Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal, July 2016

Dementia care in hospitals

Open article: Julie Vernon recounts one family's experience and asks - is it good enough? Healthcare Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal, April 2016

Stranger in a strange land: take 2

Free article: Anne Crisp gives an update on her work about ‘unprepared clients’ – those who come to counselling with no real understanding of therapy. Healthcare Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal, January 2016

References

1 Achor S. The happiness advantage: the seven principles of positive psychology that fuel success and performance at work. New York: Random House; 2011.

2 Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. American Psychologist 2000; 55(1): 5-14.

3 Seligman ME, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Netherlands: Springer; 2014.

4 Seligman ME, Parks AC, Steen T. A balanced psychology and a full life. Philosophical Transactions – Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences 2004; 29 September (1449): 1379–1381.

5 Rao A, Bhutani G, Clarke J, Dosanjh N, Parhad S. The case for a charter for psychological wellbeing and resilience in the NHS. BPS & New Savoy Conference; 2016.

6 Seligman ME. Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfilment. London: Nicholas Brearley; 2015.

7 Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: the architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology 2005; 9(2): 111.

8 Lyubomirsky S. The how of happiness: a scientific approach to getting the life you want. London: Penguin; 2008.

9 Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 2011; 3(1): 1–43.

10 Post SG. Altruism, happiness, and health: it’s good to be good. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 2005; 12(2): 66–77.

11 Argyle M. Is happiness a cause of health? Psychology and Health 1997; 12(6): 769–81.

12 Danner DD, Snowdon DA, Friesen WV. Positive emotions in early life and longevity: findings from the nun study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2001; 80(5): 804.

13 Taris T, Schreurs P. Well-being and organizational performance: an organizational-level test of the happy-productive worker hypothesis. Work & Stress 2009; 23(2): 120–136.

14 The Pursuit of Happiness. Positive psychology and the science of happiness. [Online]. The Pursuit of Happiness; 2016. www.pursuit-ofhappiness.org/science-of-happiness/ (accessed 26 July 2016).

15 Action for Happiness. Happiness action pack. [Online.] London: Action for Happiness. http://www.actionforhappiness.org/media/80216/happiness_action_pack.pdf (accessed 26 July 2016).

16 Seligman ME, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist 2005; 60(5): 410.

17 Brown SL, Vaughan C. Play: how it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. New York: Avery; 2009.

18 Cousins N. Anatomy of an illness (as perceived by the patient). New England Journal of Medicine 1976; 295(26): 1458–1463.

19 Mora-Ripoll R. The therapeutic value of laughter in medicine. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2010; 16(6): 56–64.

20 Bennett MP, Zeller JM, Rosenberg L, McCann J. The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2003; 9(2): 38.