Catherine Jackson: I’d like to start by congratulating you on your new book, Intersections of Privilege and Otherness in Counselling and Psychotherapy: Mockingbird. It’s powerful. It’s painful. It’s not an easy book to read and it can’t have been easy to write. The way you draw together your personal experience and stories with your academic interests and research packs quite a punch.

Dwight Turner: Thank you for that. Parts of it were difficult to write. Parts were difficult to research! I had periods of real ambivalence around my own heuristic exploration that I think come out in some of the sections. But that is the nature of heuristic research. It has to be exposing; it has to be transformative for the researcher. When I’ve tutored students doing heuristic work, the ones who have produced some very rich and successful work are the ones who along the way have been through some very dark times.

CJ: Let’s start with the basics. How did you come to train as a psychotherapist?

DT: In my late 20s, a relationship ended badly and I decided to do a bit of therapy to find out why I was managing things so poorly in life. The therapist I saw suggested I did a counselling foundation course, more as a process of self-development alongside my therapy. I enjoyed the course; it was very experiential; it helped me look at myself, but what stood out for me were the lectures. I left school at 18 and went straight into the Air Force, and so missed out on higher education. Those lectures ignited a fire in me to go back and study more. So, I signed up for the diploma course at the Centre for Counselling and Psychotherapy Education, although it took a couple of years before I decided I was enjoying this work and I’d see how far I could go with it.

I did a master’s while working in mental health for three years with a voluntary sector project in south-east London and for a counselling service part-time, and started my doctorate in 2012 with the aim of researching difference and otherness. That provided the basis for my book. At the time, we were basking in the glory of the ‘post-racial society’. But the world has become a lot darker since – Brexit, Black Lives Matter, and Reclaim the Streets more recently; all these movements have really come alive in the past few years. It’s a coincidence that I have published this book now. I wish it were not the case, but it is very timely.

CJ: What was it like entering a profession where there were – as there still are – so few black people and especially so few black men? It must have been quite difficult to negotiate and to negotiate other people’s responses to you.

DT: My peers on my course were fine – but that’s because race didn’t really come up during the four years’ training. So, there was nothing there to challenge. We all behaved very ‘nicely’. And I hadn’t done my own work about racial difference at that point either; I was just trying to play the game and get through the course. Race became more important when I started working in the mental health project. I was working with a service user-led group in south-east London, and the group were mainly black, and that was when I was able to bring that part of myself to my work. So, in a way, I split myself in two. The course held the adapted part of myself; it was only in my work in the outside world that I was able to be authentically a person of colour.

I think that’s a common experience for black people entering the psychotherapy profession – they’re just trying to get through the training; issues around race and diversity get left to one side. But that’s just not recognised. People may pick up on the inauthenticity from the level of irritation that goes with that, but no one ever asks what leads to this person conforming by being so ‘nice’? Because I was annoyingly nice during my course – I am far less so now. My moral compass won’t let me do that anymore.

CJ: In your book, you describe a very painful experience while you were on a retreat.

DT: Yes, I was on my own, but there were other retreatants there and we were sat round the dinner table – me, and a group of white women who were there together. They’d been out collecting stuff on a walk and one of them said something about an object they’d found in a woodpile and another one said, ‘And you know what else you can find under woodpiles.’ And I thought, ‘Have I just heard that?’

I don’t really like the word ‘microaggressions’ because I think it minimises the experience, and these events are really very insidious; they go quite deep because of the level of splitting that goes on. So, I’m sat there wondering if I’ve heard what I’ve just heard, if what’s implied is being implied – I even researched it on Google later in my room. I knew the answer, but I needed to check it, in a sense, before I could let myself think, ‘I’ve just been racially attacked, on a retreat, because my being there is scary for that person.’

Being a black man on a course, in any sort of environment, will bring up fear based around centuries of patriarchal narratives about black men. The message is, black men are a threat, white women need to stay away from them, and I, a black man, should not have been there.

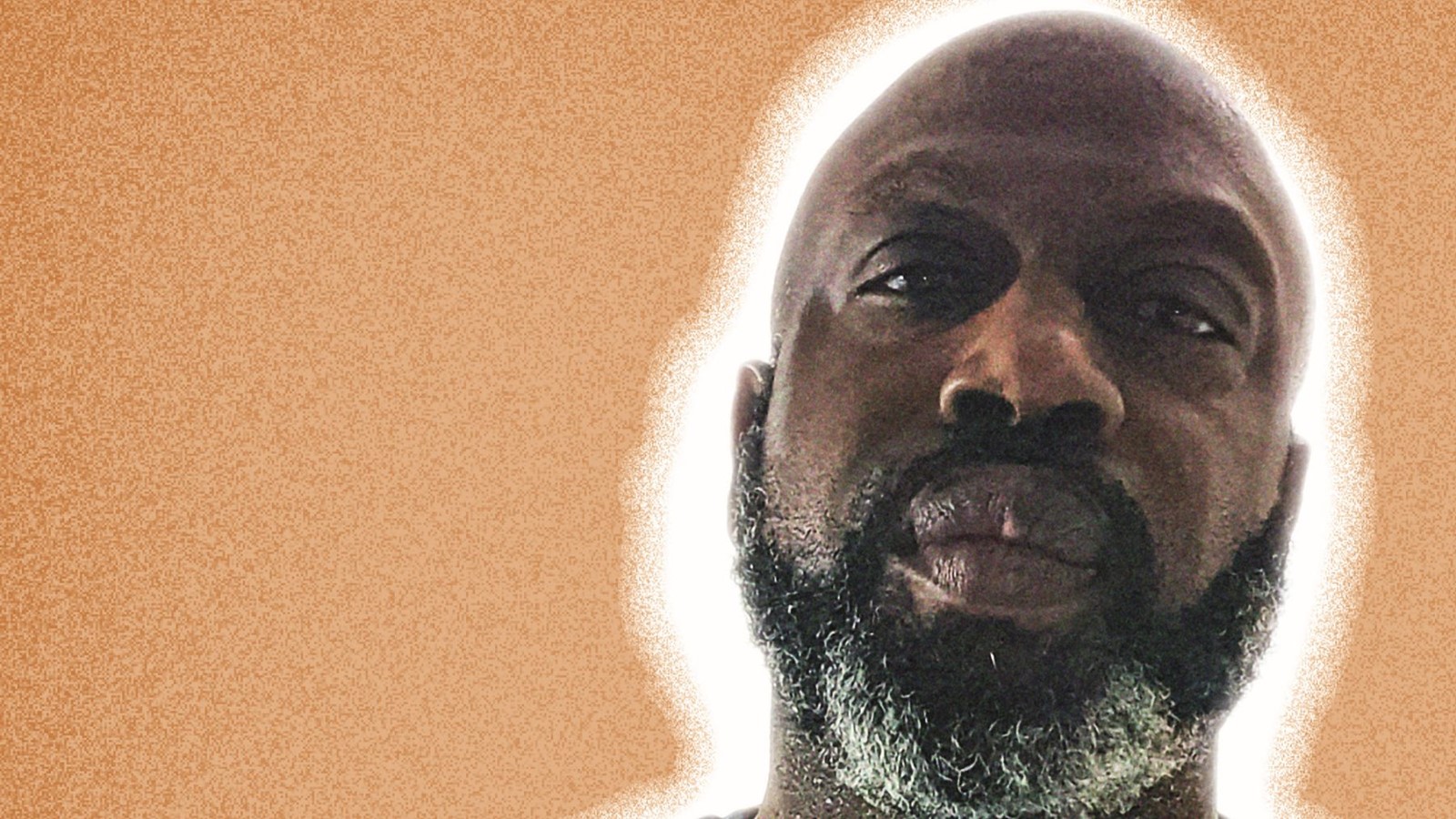

CJ: I was also struck by a photo of you in the book, as a four-year-old child, dressed by your parents in a sailor suit – as you say, playing the part of the archetypal British little boy. I guess that was a very early example of enforced adaptation. But you also write about your favourite comic characters as a child – the X-Men, all outcasts and misfits of various kinds, and Batman, who harnessed his anger into being a power for good. There was anger and a sense of injustice there. What do you do with your anger? What does any person of colour do with their anger? We have seen people protesting through Black Lives Matter and the more recent attempts by Reclaim the Streets to challenge violence against women, but does this righteous anger change anything?

DT: These protest movements are tremendously important, in my view. It does matter that we march or hold vigils or whatever we are allowed to do these days. My sense is that it is an expression of an inner morality that comes up from a very deep place. That is what these comic book heroes do – their role is to hold that sense of what is right. So many of us live under an oppressive structure – women, people of colour, disabled people, the LGBTQI+ community. For me, the anger is an expression of the moral drive to do or say the right thing. We may not always get it right but it’s important to try.

When George Floyd was murdered in 2020, I was asked by a colleague to write a blog about it and initially I said no. I didn’t feel I could add anything to what was already being said. But I remember waking up very early the next morning, looking at my phone, seeing all the images of the protests, and becoming filled with rage – I had to do something. So, at five in the morning, I went to my computer and wrote for two hours. Then I left it for a bit, had breakfast, came back and just sent it off. When we speak, when we write, when we compose songs, when we create art from that very real well-spring of anger, from that passion, then we connect. That blog brought responses from people from all over the place – professionals, lay people, activists, ordinary folk. That is what one can do with that passion, that rage at the oppressions we have all endured at some point. Use it, put it into protests and vigils, stand up for your rights, stand up and be yourself.

CJ: I was struck too by your description of your relationship with your father and what reads like quite deliberate shaming and humiliation that he visited on you when you were just a little kid and growing up. You vividly describe the shock and pain at the time. How do you now frame his behaviour?

DT: My father went through his own journey. This is a man who came to the UK in 1943 or 1944, as a young man, to fight in World War II as part of the Allied Forces, and he stayed after the war was over. One of the few times we ever spoke about race and difference, he told me how he found Britain to be very racist, even back in the 1940s and 1950s – it sounded to me like he had been through an awful lot. Often, when we are impacted by oppression and there’s nowhere for the anger to go, it comes home, and the family takes the brunt of whatever we have had to repress. We endure the microaggressions out in the world and we then have to find a way of coping with them. I live on my own, so I can just have a beer or walk down to the seafront or go for a run. I have that space. Others don’t; they go home, take it out on the kids, have a row with their partner. These are all ways of coping with the difficulties thrown at us by the world we live in. We adapt to it, but sometimes those adaptations are quite harmful to ourselves and to those around us.

I love being a father. I can’t see myself treating my daughter as my father treated me. But I’ve done years of therapy. For me it’s about recognising my responsibility as a man, as a man of colour, as a professional – obviously other identities come into play as well – and refusing to be forced into a role that society expects of me – that trope of the black father who walks out on his wife and kids; those stereotypes that are just not true. What happens is that oppressions get acted out. We are playing something out. The more woke we are to ourselves, the more likely it is that we will understand the unconscious forces that are at play and we won’t walk out; we’ll stay.

CJ: You’ve blogged quite recently about ‘toxic blasculinity’. Is that linked?

DT: Black men don’t talk about love that much. There’s a load of injunctions that sit within our culture around that. I tell my daughter all the time that I love her, but black men have been taught not to express that love, be it because, in times of slavery, you knew you were going to have your children removed from you. That must have been heartbreaking – to me, it’s unimaginable. So, to risk feeling love is enormous. That, to me, is blasculinity. It’s about those internalised experiences that prevent us from allowing ourselves to express our love, to fall in love, to fold into a loving space. I have friends in their 40s, 50s, 60s who are on their own. They’ve been in relationships, they may be in a relationship now, but they live alone. We are not gifted with the same privilege of relationship as other cultures. We have made the best of it; love is still there, but we don’t quite trust the other person, or ourselves, with it and we don’t know how to address that.

CJ: So, let’s move on to the focus of your book – intersectionality. You started the research long before it became such a focus of topical interest, but why did you choose it back in 2012 for your PhD research?

DT: When Audre Lorde wrote, ‘There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives,’ that to me is a recognition that we all in our different ways have an experience of otherness, outsiderness, which is the theme of my thesis. Our different identities experience different oppressions at different points in our life, at different ages, at different times of the day. I am not just a man, I am not just black, I am not just heterosexual; I am a multitude of different things I have grown into or that have always been with me. In psychotherapy, we talk about identity and ego as if it was just one ego, and yet each identity has its own structure around it, which makes things much more complex.

I think we make difference and diversity too simple when we polarise them into just one issue – race, gender, sexuality, whatever. We need to unpick the fact that it is much more complex and nuanced, particularly around issues of power, which we aren’t allowing ourselves to explore. Having read the work of Patricia Hills Collins, Kimberlé Crenshaw and other authors like them who wrote so brilliantly from that black feminist perspective about the oppression they endured, I wanted to broaden it even further and build into that issues of privilege and power and otherness.

CJ: But, in this time of Black Lives Matter, when there is such a polarity of blackness and whiteness and such a political imperative for it if we want things to change, is now the time to be concerned with these nuances? Some might say you are diluting the issue.

DT: Issues of race actually sit under the umbrella of identity and if we are talking about multiple different egos, the concept of intersectionality actually allows me to talk about how I am as a relational construct. How I am as a black person is identified by someone else being white. So, we go back to my example of being on my training course. If I had brought my blackness into my training, the white students would have been afraid. I have heard numerous stories from courses where that actually happened – there’s been a reaction, what we call white fragility.

Intersectionality is about recognising that race, gender, sexuality, disability – whatever the oppression is – are interconnected pillars that hold up the intersectional approach, and it is only when we recognise the interconnectedness that we recognise that we all have that intersectional experience. It’s not just the polarities, it’s the collective experience we are looking for here. That’s why I subtitled the book ‘Mockingbird’. I am deliberately referencing the book by Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird, because, for me, it shows that intersectional approaches are even there in our literature and have been for generations.

CJ: You write: ‘Equality is not about closing the attainment gap, equality is the right to self-identify.’ Another resonant sentence. What might that look like in the UK today?

DT: Heterosexual, white, upper-class men hold the power, and we are all trying to close the gap by getting to the top of the pinnacle. The trouble is it is a pinnacle; there is no room for everyone there at the top. One of the things I love about the LGBTQI+ community is their ability to self-identify. I don’t care how many categories they have – the issue for me is that they are actually thinking about who they are, because that is taking the power away from heteronormativity. Heteronormativity says, ‘This is how you are supposed to be, and we will shame you into being this,’ and LGBTQI+ people are saying, ‘I will take pride in that’ – that is very powerful. People of colour have questioned the term BAME recently and a lot of us, me included, have thrown it out. I think that is a great start to a longer conversation about who we are and how we want to identify. It doesn’t have to be one category, it can be myriad categories, as long as we hold them lightly. Any identity is only good in the moment we have created it. Otherwise, it pins us to the wall, which makes no sense.

CJ: I am struck by what you say in your book about adaptation and how it ‘kills off’ authenticity. You write: ‘To regain our humanity and become more than beast again, we must unshackle ourselves from the silky binding of adaptation.’ What does that unshackling look like?

DT: This is shadow work, in a way. It is difficult, painful work to look at the adaptations placed on us and that we have placed upon ourselves. I think it is only by working with the unconscious that we start to unlock those shackles, those chains of intellectual stupidity that we give ourselves. It’s also about listening to one’s inner voice and stepping out of the inhumanity placed upon us by those who need to project their fears of their own otherness. When we dehumanise somebody, we make them less than. So, when we say, for example, in the black community, ‘We are kings and queens,’ we are taking back who we are and not letting someone else define us.

CJ: Do you see black therapists breaking free of the performance of white therapy?

DT: I see it more and more. We are all taught how to be a therapist, but it’s how we bring ourselves to the work and how we choose to develop ourselves in the profession that frees us from those shackles. There are black therapists out there running workshops on the black therapeutic process and there are more and more black therapists taking part in that and breaking the chains of white therapy by becoming more the therapists they want to be, including myself.

CJ: Your daughter is just five years old. Can I end by asking what is your greatest wish for her in her life?

DT: My hope for her is that, when I pass the baton on to her, she runs with it, and whatever strides I and my generation have made – and some have been made – she builds on them in her own God-given way and has a happier life than I have. Now I’m crying – I didn’t expect that!

CJ: Thank you, Dwight.