In 1891, a train from Basel in Switzerland was so overcrowded that the Münchenstein Bridge couldn’t take the strain. When it collapsed, over seventy people died. This is one of many disasters listed in Wikipedia’s section on bridge failures.1 What’s interesting is that, prior to 1900, overload was a relatively common cause of bridge collapse. After 1900, it wasn’t. We got the message that exceeding weight-bearing capacity was a dangerous thing to do and we became more serious about preventing overload. There is a parallel here with overload in the workplace – is it possible that we could learn a similar lesson?

Unfortunately, current trends are heading the wrong way, as stress at work is becoming both more common and intense. A recent Megatrends report from the CIPD noted that, while working hours in the UK remain fairly stable, people are increasingly being asked to meet tighter deadlines with fewer resources.2 Do you work with people who are casualties of this approach? When giving my keynote presentation at the BACP Practitioners’ Conference, I asked my audience this question. In reply, a packed roomful of hands shot into the air. As prevention is better than cure, now is a great time to step back, take stock, and address the growing epidemic of having too much to do.

This article identifies four contributors to the trend of increasing overload, while also describing recovery strategies that can help our response. I make a distinction between functional and dysfunctional overload. Functional overload refers to temporary episodes of busyness that we recover from without injury. Dysfunctional overload is a more persistent condition where the strain of having too much to do results in harm to wellbeing, relationships and/or performance.

Overload factor 1: email

Can you remember a time when you felt excited to see new emails in your inbox? Things are different these days: in the time it takes you to read this sentence, another twenty million emails will have been sent. Global traffic grew from thirty billion emails a day in 2003 to two hundred and five billion in 2015; this is estimated to rise to two hundred and forty-six billion emails a day by 2019.3 Reading and writing emails now consumes more than a quarter of many people’s working week.

The concept of ‘overshoot and collapse’ is relevant here. In population dynamics, overshoot is where the population of a species exceeds the carrying capacity of its environment. If this happens too much for too long, environmental conditions decline, leading to a collapse in the population. This can happen with algae in ponds or with swarms of locusts when they strip a region’s vegetation bare. Overshoot is too heavy a load; collapse is where this might lead. So what happens when our carrying capacity for electronic communication is exceeded? If swarms of emails consume our working weeks, will our ability to function well collapse?

Overload factor 2: paperwork

In 1992, when I started working in a specialist mental health team, I’d complete a four-page assessment form when seeing new clients. By the time I left in 2010, the ‘new person pack’ had grown to include twenty-seven pages of forms to fill in. I began to dread new assessments, because the overshoot of data collection requirements threatened to collapse the therapeutic value of my consultations. Linked to this, I experienced a sharp decline in my morale and job satisfaction, leading me eventually to resign.

My troubles with the paperwork trend are illustrative of a much wider pattern. Surveys show concerns in a range of other occupations, with people finding it difficult to do the work they trained for because they’re spending so much time filling in forms.4,5 The threat of litigation is one of the drivers for defensive paper trails and there may be seemingly sensible arguments for each new administrative demand. But when the cumulative impact of additional burdens undermines the effectiveness of the core work task, a line needs to be drawn.

In their classic text, Career Burnout, psychologists Ayala Pines and Elliot Aronson warn that a key risk factor for burnout is existential, when people lose the sense that their work is meaningful.6 That is more likely when someone’s core role purpose is hijacked by other demands.

Overload factor 3: a context of austerity

We live at a time when many organisations are under pressure to cut spending. Teams and their budgets might be shrinking while the workloads they face aren’t. This is often after years and years of ‘cost-improvements’ and ‘efficiency savings’ that have removed any buffering slack. These are times of squeeze, and it is unrealistic to expect everyone to carry on with business as usual when they’re no longer resourced to work in the same way or at the same level.

Overload factor 4: self-criticism

When I work with teams that are experiencing overload, I often hear people describe the subtle pressure to put on a brave face. The whole team might be struggling but because each person sees everyone else’s brave coping exterior, they think they’re the only one having trouble. Contexts like this make it more likely that people will blame and criticise themselves when they’re not succeeding in their work. Self-criticism is not only a recognised risk factor for depression, it also becomes an internal voice pushing people to work harder, in a way that drives them further into overload.7

Starting from where we are

These are some of the factors fuelling dysfunctional overload – you may recognise others. It can feel depressing to consider where current trends are taking us. Yet an essential first stage in addressing any problem is simply to recognise it. When I run courses on resilience, we start by looking for examples of situations that have gloomy beginnings but where people’s responses to these lead to better than expected outcomes. The long list of bridge disasters, for example, might seem rather morbid. But each tragedy of collapse fuelled the desire to understand how to build safer structures. Through a process of ‘post-traumatic growth’, we developed ‘loading literacy’ where we understood more about how to build strong support and keep within the limits of carrying capacity. Because workplace counsellors see the harmful consequences of overload in our clients, we are uniquely placed to sound the alarm about this issue. But what strategies for recovery can we offer?

Three letters I often find instructive are ACT, standing for acceptance and commitment therapy. Acceptance is about acknowledging the situation we face. It becomes our starting point. Commitment is what we bring to addressing this. We may not have a solution, but we can be interested in looking for constructive pathways of response. In this spirit, here are three recovery strategies I find useful.

Strategy 1: know where you are on the hill

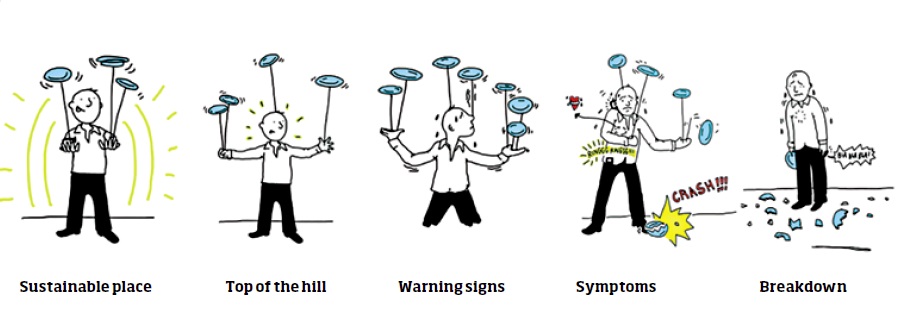

Some might argue that pressure is good for you because it motivates you to perform at a higher level. That’s true up to a point, though the key is to know where that point is and whether you’ve stepped beyond it. A pivotal insight in stress management is to understand that when in overload, more is less: trying to do more can make you less effective. The human function curve maps out this relationship between pressure and performance in a graph that has increasing pressure as the horizontal axis, and performance ability in the vertical.

When we have little or no pressure, there is less challenge to engage us and so we don’t perform so well. I think of circus performers spinning plates – it takes a few plates to absorb our attention in a way that draws out our strengths. We’ll have times when we’re rising to a challenge where we perform even better, and our peak performances may be further turbo-charged by adrenaline release. When we’re at the top of the hill we’re performing at our best and it can be very satisfying. If at this point we then face an additional demand, say if an emergency comes up, we can get pushed over the hill into overload, where we function less well. Have you had that experience of being just busy enough, but then pushed further into a spin where your mind races so much that you lose track of things?

When working with people who are struggling with stress, I encourage them to familiarise themselves with the different zones on this graph. We each have a characteristic stress signature for how we experience the different stages of overload. I ask people what the first clues are that they are becoming stressed. These are their warning signs. Then we explore what might happen if the pressure got worse, what symptoms of stress they might experience. And if pushed further, are there ways they might break down or collapse? We map out signs and symptoms of stress by looking at five domains, guided by the following questions:

- Feeling/emotions – how do you feel when you’re stressed?

- Thinking – what happens to your thinking?

- Body – what do you notice in your body?

- Behaviour – do you act differently when stressed? If so, how?

- Relationships – what happens in your relationships?

Relationships – what happens in your relationships?

In each of these areas, we’re following an enquiry guided by the question: ‘How do I know I’m stressed?’ Knowing where you are on the hill is a foundational recovery strategy. The best place to be is at a sustainable pace just before the top of the hill. From there you are able to rise to the occasion in emergencies, rather than tip into a spin. If you’re over the hill, you can recognise you’re no longer at your best, and that you’re at risk of symptoms or, if pushed further, collapse. Then you can look at ways of protecting yourself.

Table 1 - example of stress signature signs and symptoms

Stress signature: when I'm stressed I tend to ...

| Domain | Warning signs | Symptoms |

| Feeling | Tense, sulky | Anxiety, depression |

| Thinking | Racing mind | Hard to concentrate |

| Body | Sweaty, tight | Skin rash, headache |

| Behaviour | Go quiet | Mistakes, accidents |

| Relationships | Irritable | Rows, become isolated |

Strategy 2: commitment cropping

When in overload, more is less. Rather like hedges that get unruly if untended, our commitments tend to sprout over time and need regular trimming back. Here is a commitment cropping practice I use both for myself and with clients.

- First, list the different roles you play, both at work and at home.

- List the expectations and obligations that come with each role.

- Reflect on how it feels to look at this list – is it satisfying to consider or does it make your heart sink? If you’re in overload, you’re likely to feel uncomfortable because of the size of your list. If you feel overwhelmed, remember the letters ACT (standing for acceptance and commitment therapy), and then apply your commitment in step 4.

- Run through your list and ask yourself how you’d feel if you were to delete each item. For some items this would feel unacceptable, but for others you might experience relief. If you’d feel better by removing an item, ask yourself who’d notice if you did, and what the consequences would be. If it would be more of a positive step than a negative one to resign from a task, or even a role, consider doing that.

Strategy 3: facilitate a cultural shift of stress awareness

When I run courses with managers, I ask them to consider the impact on a team or organisation when people are at different places on the hill. If a workforce is stuck in serious overload, what is likely to happen to staff sickness rates, turnover and productivity? If people are more irritable, at risk of accidents or are depressed, what are the costs to the organisation? While this might sound obvious, common sense is not always common practice. A cultural shift is required to move away from seeing stress purely as a personal issue.

A useful reference comparison here is with back problems. If someone has back or other joint problems that are made worse by heavy lifting or sitting in an uncomfortable chair, we don’t tend to direct them to endurance classes to teach them to put up with the discomfort. A more common practice is to take an ergonomic approach and consider workplace design factors that might improve comfort and performance. As postural habits do have an impact, there is a role for some personal training, but this is best seen as a complement to addressing context issues. Similarly with overload, personal strategies can be really helpful, but they need to be supported by a stress-aware organisational culture that recognises the need for commitment cropping when people are in overload.

Maximum and optimum

A workshop participant once said to me ‘It is interesting what you say about spinning plates, because I used to work at a plate factory’. He told me that, before Christmas each year, the demand for plates was higher, so they speeded up the conveyor belt to increase productivity. However, they’d found they could only work at the higher speed for about six weeks before the breakage rate rose to unacceptable levels.

What would the workplace look like if organisational cultures really understood the difference between optimum and maximum work rates? That’s the difference between the sustainable pace just before the top of the hill, and the flat-out working of peak performance. Rather like with bridges, we wouldn’t want the normal load to be the maximum safe load. Otherwise, those unexpected occasions when things are busier than normal would push us, or our organisations, into collapse.

Dr Chris Johnstone is director of CollegeOfWellbeing.com and one of the UK’s leading resilience trainers. With a background in medicine, psychology, counselling and coaching, he’s been involved in teaching stress management and resilience skills for over thirty years. For information about online resilience courses he offers, including a Resilience Practitioner Training, starting in September 2016, please see collegeofwellbeing.com

More from Counselling at Work

The sacrificial organisation

Open article: Why is scapegoating so common at work? Vanessa Avery explains how it can manifest and what organisations can do to create a culture that protects against it. Counselling at Work, Spring 2016

Trauma support in Paris

Open article: In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in Paris, Andrew Kinder provided post-trauma support to employees working in the city. He reflects on the experience. Counselling at Work, Winter 2015

Sex offenders, pornography and the workplace

Open article: How would you work with a sex offender in a workplace setting? Juliet Grayson, Chair of (StopSO), challenges some misconceptions and offers advice. Counselling at Work, Autumn 2015

References

1 Wikipedia. List of Bridge Failures. [Online.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_bridge_failures (accessed 7 June 2016).

2 Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. Are we working harder than ever? London: CIPD; 2014.

3 The Radicati Group. Email Statistics Report 2015–2019. [Online.] http://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Email-Statistics-Report-2015-2019-Executive-Summary.pdf. (accessed 7 June 2016).

4 BBC News. Nurses spending too much time on paperwork. 21 April 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-22237435 (accessed 7 June 2016).

5 The Educational Institute of Scotland. Major new survey highlights heavy teacher workload. 20 May 2014. http://www.eis.org.uk/Teacher_Workload/survey_stress.htm (accessed 7 June 2016).

6 Pines A, Aronson E. Career burnout. New York: The Free Press; 1989.

7 Ehret AM, Joormann J, Berking M. Examining risk and resilience factors for depression: the role of self-criticism and self-compassion. Cognition and Emotion 2014: 29(8): 1-9.