What are the emotional and psychological factors that limit a thriving practice for therapists? Based upon many years of supervising practitioners, I’ve reflected on this question, particularly from working with recently qualified therapists who are struggling to build up their private practice. They frequently appear to get stuck at certain thresholds of client numbers that seem difficult to get beyond, whatever effort and marketing manoeuvres the therapist makes. Hovering for months between four and eight clients per week can become frustrating. However, once they get through that glass ceiling, it suddenly seems less difficult, and their practice then jumps relatively effortlessly to 10 or 12. But then a similar thing occurs around that number.

There are many practical and emotional reasons why these things occur, and so many intangibles involved that we may well feel unable to make any conclusive assertions. However, applying a particular ‘psycho-logic’ suggested decades ago by David Malan,1 I have come to hypothesise a correlation between certain fundamental issues central to the therapist’s self-regulation as a practitioner, and how large, manageable and sustainable their practice can become. These issues only become fully evident when I get actively involved in the supervisee’s personal and professional development, and actually care about them thriving as a practitioner. Without that engagement on my part, manifest in how I handle the inherent parallel processes, I can’t expect much impact. I have clustered these fundamental issues into three topics:

- The therapist’s capacity to digest and compost the emotional impact of the therapeutic relationship as a bodymind process.

- The therapist’s capacity to embrace/inhabit ‘enactment’ as the central paradox of therapy.

- How entrenched or flexible the therapist can be in their ‘habitual position’, ie their own unconscious relational ‘construction of the therapeutic space’.

In this series of articles I will attempt to clarify these notions and ideas, and how they impact on our practice, specifically on how thriving and sustainable it can become, for our clients, ourselves and the whole endeavour of private therapeutic practice as a business proposition (which some of us want and need to make a living from). Over the years, I have run several CPD workshops on this topic, with various cross-modality groups of therapists, giving me some insight into how the typical practitioner thinks about these issues and processes them, and more generally where our discipline is at in terms of the sustainability of practice.

Investment in marketing shows diminishing returns

Over recent years, many therapists have got their act together in terms of the business and marketing mechanics of running a private practice. The internet has given easy access to increasingly sophisticated tools and services, which make those tasks manageable. Businesses specialising in supporting self-employed therapists, as well as online directories and referral networks, have raised the professionalism to a fairly ubiquitous level, meaning that on this level there now remain only diminishing returns for establishing or expanding one’s practice.

Most workshops available for practitioners on the topic of making a living focus on the business skills needed. Other workshops focus on the therapist’s own ambivalence and personal issues around money, linking their struggles about charging money with underlying psychological issues of self-worth. This is a valid link to make and explore, as becomes apparent in supervision in situations where clients mess us around in terms of payment – our own issues are readily hooked then. However, many of these workshops – quite apart from their dubious narcissistic overtones – are based on what I find questionable ‘go-getting’ assumptions, values and attitudes (‘You can create abundance’, ‘You deserve everything you want’) and I wonder whom they serve. They certainly don’t address the underlying tensions and vicissitudes that are necessarily inherent in our intersubjective practice.

A blank cheque for exploiting human suffering?

There is a basic conflict structured into therapy – especially in private practice – between ‘love’ versus ‘business’, which none of us is immune to or can escape. It’s important to face this issue squarely, and not shrink from it. However, the simplistic polarisation between ‘love’ and ‘business’ easily becomes a trap, dreaded by therapists, epitomised by the common client question: ‘You’re only nice to me because I pay you. Would you continue seeing me [ie loving me] if I wasn’t paying your fee?’

This is a real question and it deserves a solid therapeutic answer. What this may be is not straightforward or even possible to figure out if we take the question at face value only. What helps us avoid falling into the trap is the recognition that the question contains an even deeper polarisation which is a necessary part of the relational dance co-created between client and therapist, or in any human relationship, for that matter: both ‘love’ and in ‘business’ we struggle with our tendency towards objectifying the other, turning them into an object to satisfy our needs. This fundamentally valid impulse pulls, in dynamic tension, against the equally valid impulse to treat the other as a subject, and to take their needs into account – or, for some of us, to go even further and subjugate our needs to theirs. How we mutually use each other as objects while also recognising each other as subjects, is both constitutive as well as destructive of the self-other boundary that forms our individual identity – and its undoing.

The more we understand our subjectivities from a depth-psychological perspective, the more we recognise how Winnicott’s ideas on the ‘uses of an object’ are relevant to how we negotiate the ‘deal’ of therapy with each client. Our early histories – the client’s and the therapist’s – and how as infants and children we were used as an object, and how we were allowed to use the other as an object, are of huge significance in the therapeutic contracts we make, whom they serve and how sustainable they are.

These are contested interpersonal territories, and the inherent struggles – never entirely devoid of collective power struggles – cut across all the levels of our being, from the most personal to the familial, sociocultural and political-economic. We want to be acutely aware of how we may be falling into neo-liberal stereotypes of late-capitalist-relating, and how our practice enacts the alienation process – identified by Marx – which turns natural and human resources into commodities to be bought and sold. And, in therapy, we are thinking specifically in terms of suffering and the need for attachment and love.

Rather than trying to overcome these implicit struggles with pat recipes for individual prosperity, I aim to get to the bottom of the emotional sensitivities and relational vicissitudes inherent in therapeutic practice, respecting the mutual human attachment that always forms the foundation of our work.

Fully qualified! Ready to practise as independent practitioners?

The main assumption throughout the field seems to be that once we have qualified and our certificate is hanging on our consulting room wall, we are sufficiently prepared to translate the competencies we have acquired in training into running a therapeutic business and all that entails: steadily maintaining our practice week in, week out; managing a substantial number of clients with reliability and discipline, including supervision; taking responsibility for our own professional development and requirements as independent reflective practitioners; running a self-employed business and competing in the marketplace.

I don’t think this assumption is born out in practice: even after 450 or more sessions in the context of placements, the ‘jump’ into the rigours of running a private practice (especially with anything resembling the kind of caseload that one can make a living from), constellates all kinds of emotional issues and dilemmas, which many therapists are not prepared for. It’s one thing to be enthusiastically committed to two or three training clients, for whom I receive plenty of supervision and spend a lot of reflection time on (eg writing case studies), it’s quite another thing to maintain the same kind of presence and engagement with 10, 15 or 20 sessions per week. The surprising successes of novice therapists, sometimes on a par with very experienced practitioners (if the outcome research can be believed), has been attributed specifically to that beginners’ enthusiasm and concentrated attention, which gets showered on our first clients.

This is underpinned by our capacity for balancing our emotional spaciousness between work and home, between ourselves in the role of therapist and as a person with a life. In order to get some reflective leverage on how we actually do this balancing act in practice, and before I dive into the three underlying issues across the subsequent articles, we need to establish some important and undertheorised elements of the therapeutic position: the fragmented diversity of the psychotherapeutic field; the lack of inner integration within the therapist, despite the advances of the integrative movement; continuing paradigm clashes obstructing such integration; and the therapist’s relational stance.

Has my training prepared me sufficiently?

One of the first difficulties freshly qualified therapists encounter is that paying clients are liable to come in cold, without any prior notion or understanding of what they are letting themselves in for. Or, just as tricky, clients may turn up as ‘therapy junkies’, who have previously sampled a range of complementary and counselling approaches, and have in the process become self-proclaimed experts.

Before venturing into private practice, the therapist will have completed many client hours in placements – nevertheless, it often comes as a shock that this is entirely different from skills practice with peers, who bring both willingness and a capacity to engage in the process. Many clients who turn up for their first session labour under significant misapprehensions – derived from the media, or confusions with other helping professions – as to what they’re paying for and what the practitioner is offering. These preconceptions on the client’s part can be difficult to negotiate, and make it abundantly clear that the range of clients and the problems they bring are much greater than our trainings have prepared us for.

Several decades ago, therapists also had to contend with the additional difficulty that they had been trained, within an atmosphere of tribal dogmatism between the approaches, into a somewhat blinkered and one-dimensional therapeutic position. This made it more difficult to cater for a wide variety of clients and their diverse needs, and made sustainable practice more difficult to achieve. This tendency has lessened with the rise of the integrative movement over the last 25 years, allowing therapists to tailor their approach to the needs, values and belief systems of their clients. Therapists can now be responsive in terms of the theories and techniques they apply, which must be a good thing in terms of the working alliance.

However, as precious as it is, the integrative movement has not made our practice more sustainable, contrary to what I would have expected 20 years ago, and I have been looking to find explanations for this. The best reason I can offer is that the integrative impulse is quite validly pointing us towards some future possibilities of coherence as a profession, which we are not manifesting yet. As long as the outer integration of theories and approaches is not matched by a corresponding integration within the therapist (specifically in terms of self-regulation and containment), we cannot expect ourselves to manifest a more self-sustaining and sustainable practice.

What we might mean by inner integration is a complex question, beyond the scope of this article, but let me include three points relevant to the current topic:

As in any evolving system, one of our main challenges is to find a therapeutic stance that is both responsive and stable, flexible and containing – for our clients and ourselves. So integration, driven originally by the impulse towards greater flexibility for the sake of our clients, must be an ongoing, dynamic process, which operates in dialectical tension between these evolving polarities. As a field, one of the main dividing lines obstructing integration – both individually and collectively – has been the polarisation between humanistic and psychodynamic orientations. Traditionally, openness and evolving flexibility have been championed by the humanistic approaches, in pursuit of human potential and at the expense of containment and boundaries; and the psychodynamic tradition has emphasised stability and containment, some would argue to the point of rigidity and ossification. In order to transcend this polarisation, what we need, also, is humanistic stability and psychodynamic flexibility, which is something we can currently only find sporadically, rather than established throughout the field – I will say more about this later when we consider the relational stances underpinning these traditions.

It is one of the under-theorised aspects of the integrative movement that a plethora of therapeutic options is not necessarily containing for the client, who may experience the therapist as trying to be all things to all people, yet never taking a firm position that one can engage and also fight with.2 But, importantly for our topic here, neither is an integrative approach very containing for therapists – in most cases we do not actually feel very ‘integrated’, but more eclectically confused, oscillating between different therapeutic impulses, theories and approaches.

As we will see, the stress of the therapeutic position, which makes practice difficult to sustain, arises significantly out of uncontained, subliminal, dissociated and un-thought3 or unformulated4 processes in the relationship. Therefore, the very notion of ‘containment’, deriving as a significant therapeutic principle from psychoanalytic thought, needs thorough investigation before it can become a helpful and sustaining, rather than a demanding and persecutory, idea.

The lack of integration within therapists, in spite of the integrative developments, is due to some outdated, linear assumptions and underlying paradigm clashes which remain unresolved in the therapist’s mind. This makes it more difficult to embrace our own vulnerability as ‘wounded healers’ within the therapeutic position, and leaves us susceptible to, and reactive against, the kind of intractable dilemmas that necessarily need to arise in everyday practice when we are engaging at relational depth. Unless we feel ‘held’ in these dilemmas (by our tradition, our elders, our theories, our supervision, our community and peers), they will become draining and exhausting. What are these paradigms clashes that interfere with us feeling ‘held’?

Let’s look at them in more detail.

The hidden conflictedness of the therapeutic position

A key source of unprocessed bodymind stress for therapists is the gap between widespread idealising and oversimplifying assumptions as to what therapists ‘should’ be experiencing and doing in practice, on the one hand, and the actual conflictedness of the therapist’s experience, both in terms of the working alliance and their internal process. The general public, other helping professions and clients and therapists themselves, ‘believe’ the public preconception that therapists are like ‘doctors for the feelings’, doing their predictable and replicable job of applying standard theories and techniques appropriately to the client in front of them.

These still dominant assumptions conceive of our work as too linear and instrumental and give us a disembodied, reductive and unrealistic idea about the degree of internal conflict and pressure we necessarily experience in the therapeutic position. We will explore this later in a lot more detail, but it may be helpful to summarise a key point upfront.

The therapist’s bodymind will, instinctively and unconsciously, find mechanisms of protecting itself against this largely subliminal onslaught of unacknowledged conflict, unprocessed stress and apparently unprocessable distress, by attempting to reduce the overall degree of conflict in the system. It typically does this by avoiding or minimising transferential and countertransferential pressures. The therapist thus loses access to vital information in the therapeutic relationship, reactively counteracting or short-circuiting threats to the working alliance, making it more difficult to anticipate and contain relational ruptures, which in turn increases the pressure in the system further.

One of the main problems affecting the sustainability of our practice, therefore, is a pervasive naivety about the relational bodymind complexity that is necessarily inherent in practising our ‘impossible profession’. This naivety is partly due to therapists trying to reflect on their practice and process its bodymind impact by resorting to dualistic medical model assumptions, imported into our profession from the natural sciences, even more so about themselves and their own bodymind functioning than about the client’s.

In what follows, my argument hinges on the recognition that such linear quasi-medical principles are inimical and alien to the essence of our work if used as exclusive or dominant explanatory frameworks, but necessary and helpful if taken into account as one contested perspective among others (neither falling into nor categorically refuting dualistic perspectives).

Lingering medical model assumptions

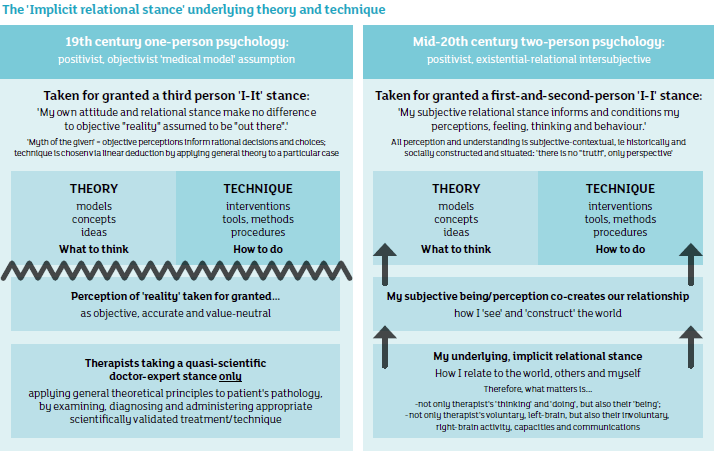

Traditionally, therapeutic approaches used to be characterised and differentiated, compared and contrasted, by their theory and technique – a useful distinction which goes back to the early psychoanalysts. However, in those days the therapeutic endeavour was exclusively conceived of as ‘treatment’, and the medical model was taken for granted as the underlying paradigm. Remnants of such 19th century assumptions and positivist, third-person, objectifying attitudes are still pervasive throughout the field, and influence our ideas of boundaries, accountability, pathology, therapeutic action and many others, even among therapists who philosophically disavow the medical model. As long as we are thinking about therapy only in terms of theory and technique, we are unwittingly assuming a scientific stance, which examines the case in front of us in the context of our general theoretical understanding (theory), further assuming that a correct ‘diagnosis’ will consequently lead us to linear conclusions as to the best treatment to be administered (technique). It is only on the basis of those paradigmatic assumptions that we could ever have hoped to deduce our interventions purely from theory and technique, and to be able to characterise our approach simply by these two parameters, important as they are.

Traditionally, even therapists who fiercely oppose the medical model can often be seen to adhere to their particular brand of theory and technique. I can remember that in my early days as a therapist, even while denouncing any idea or need for diagnosis as pathologising and counter-therapeutic, I used to operate from a particular theory-led, fixed stance, built on the assumption that ‘my’ theory and technique was valid and applicable to all clients at all times – so why would I need diagnosis? What I failed to recognise at the time was that my thoroughly reparative stance and assumptions about therapy were always already predicated on the conviction that there was a ‘wound’, a ‘deficit’, a problem that needed ‘fixing’ and that would thus justify my existence and role as a therapist. The inescapable implication that my fixed perception of the urgent need for repair required a diagnostic stance on my part, was not reconcilable with my philosophical beliefs: as long as I’m invested in fixing, there will have to be diagnosis of what’s broken. And in order to maintain my pervasive diagnostic stance, there would have to be an implicit theoretical frame, which in turn gave me the rationale for a distinct set of techniques. This was all operating implicitly, unconsciously, while I was fancying myself without diagnosis, and intuitively beyond theory and technique. It was operating on a prereflexive level within me – as my implicit, underlying relational stance.

Our underlying relational stance

The more we have come to see therapy not just as a treatment, but also as a first-and second-person encounter, the more we recognise that our own contribution to the relationship co-creates that encounter. We, therefore, need to take into account our own relational stance and attitude (conscious and unconscious), which can no longer be assumed to be objective and neutral to the supposed ‘treatment’, but intrinsic to the intersubjective field. It is the shape of this field, including ourselves as wounded healers within it, which – for better or worse – is decisive to the eventual shape the therapeutic process will take.

These statements are now well-established assumptions among the majority of therapists, with the medical model now comprehensively deconstructed as the dominant paradigm for psychotherapy. A simple way of phrasing this would be as a distinction between the 19th century assumptions of modernity and the 20th century assumptions of the postmodernists, who comprehensively critiqued the dualistic, positivist and reductionist beliefs of earlier generations (ie their parents and grandparents, including their therapeutic forefathers).

In the modernist paradigm, the doctor examines the patient much like a scientific observer/researcher would, establishes a diagnosis which correlates the findings of the investigation with generally known theories and principles, and then prescribes and administers the most appropriate treatment indicated, according to that diagnosis. This paradigm assumes that objective truth is ‘out there’, irrespective of the therapist’s own subjectivity, and that healing arises through the ‘correct’ treatment.

In the postmodernist paradigm, the client is not an inanimate object, but another human, whose subjective reality I can only hope to meet and engage with through my own subjective humanity. Whatever perceptions, understandings and interventions I come up with, they are considered as always already embedded and constructed by my own history and context, which is why postmodernists say: ‘There is no truth “out there”, only perspective.’ This paradigm assumes that reality is perceived, constructed and interpreted via the therapist’s own subjectivity, and that there always is an underlying, implicit relational stance, whether or not the therapist is aware of it and acknowledges it: there is no ‘pure’ or ‘objective’ theory and technique, uncontaminated by the therapist’s subjectivity. If possible at all, healing here is seen as arising through intersubjective dialogue, through the meeting between two vulnerable humans, and their mutual exploration.

I summarise the contrast between the classical, positivist, one-person psychology assumption and the modern, relational, intersubjective, systemic, two-person psychology assumption in the following graphic.6

Polarisation between ‘medical model’ versus ‘antimedical model’

The distinction between these two contrasting philosophical underpinnings will become relevant later, when we reflect upon which assumptions support us as therapists in noticing and then processing the impact of our involvement in the therapeutic encounter, on ourselves and our own bodymind; and what kind of assumptions get in the way and serve to keep us oblivious of our own vulnerability and susceptibility to retaining, sponge-like, the traumas and conflicts inherent in the work, which our empathy has necessarily opened us up to.

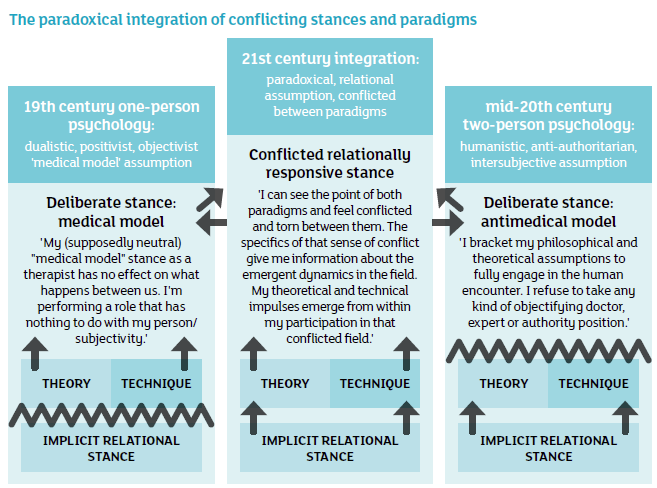

However, for our purposes here, we need to go beyond that simple binary historical distinction between the origins of therapy in 19th century medical model assumptions on the one hand, and the mid 20th century postmodern insistence on two-person psychology on the other.5 While the deconstruction of one-person psychology was entirely necessary, we can wonder whether we haven’t jumped from the frying pan into the fire – or at least from one extreme to another – by postulating an exclusive two-person psychology paradigm.

I have suggested elsewhere that the various perspectives that oppose the classical ‘one-person psychology’ paradigm – humanistic, existential, intersubjective and relational – are caught to some extent in an equally dogmatic antimedical model stance. By validly critiquing the medical model for its underlying objectifying stance, many of us have created an equal and opposite oversimplification, which reduces therapy to nothing but an authentic, dialogical, I-Thou encounter between existential equals – a meeting which supposedly becomes therapeutic only through the mutual recognition of each other’s subjectivities.

This anti-position, as valid as it is in many ways, has a tendency to shrink our conception of how complex these subjectivities actually are: by falling into the wide open trap of Cartesian dualism, it usually ends up equating subjects with their reflective, cognitive capacities, reducing them to ‘flatland’ personalities, without depth, passion or bodies, sometimes to the point of not even recognising the existence of unconscious processes.

If we do not want to reduce our conception of the relationship to an exchange between conscious personalities, we need to include what, following Wilber, we might classify in the widest sense as both pre-and transpersonal modes of being and communicating. There are many precious and satisfying aspects of human relating that do not depend on mutual recognition between persons, but involve Winnicott’s ‘uses of an object’, ie prereflexive and primary intersubjectivity modes of consciousness and asymmetric relationships that fulfil object-seeking needs and desires. Based on a valid critique of the power-over paradigm inherent in the medical model, champions of the antimedical model usually seek to avoid abuses of power, and try to maintain equality at all costs; but by avoiding the perils of power differentials altogether, we then lose access to the very origins of our woundedness in contexts of early development that are characterised by intense helplessness and powerlessness.

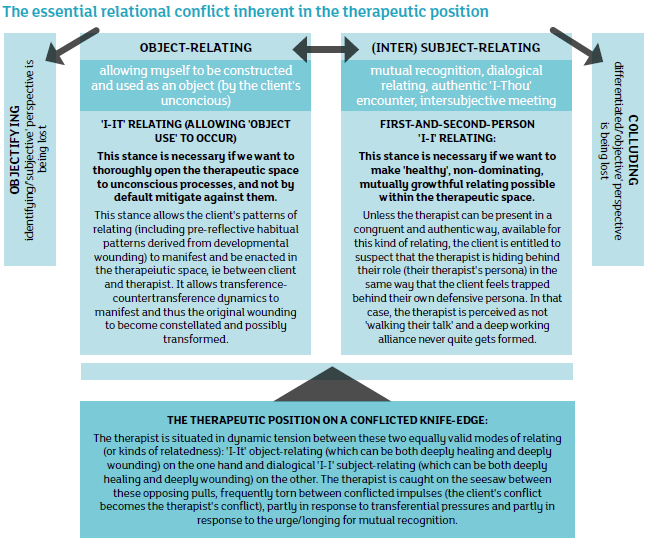

For these and many other reasons taking us beyond the current topic, both medical and antimedical model, ‘one-person’ and ‘two-person’ perspectives – contradictory and irreconcilable as they are – contain elements essential to the therapeutic endeavour: we cannot get rid of either one of them without foreclosing the essence of the therapeutic process. Or, to put it another way: therapy arises as a helping profession – ie becomes culturally necessary – in the conflict zone between these two perspectives. Therapy becomes productively possible as a practice when the therapist can situate themselves squarely on that conflicted knife-edge and inhabit the dynamic process of that battle, as it manifests in each particular client-therapist dynamic.

A third position transcending the paradigm clash

In order to understand the psycho-biological impact of inhabiting the therapeutic position deeply and accurately, it is, therefore, most realistic and helpful to conceive of it as profoundly conflicted and inherently paradoxical: as a therapist I need to feel torn between these various conflicting paradigms, between I-it and I-I relating, between objectifying and subjectifying, between treatment and human encounter, between ‘allowing myself to be used as an object’ and mutual recognition.

In formulating it like that, I immediately experience more spaciousness for the lived reality of my work, and feel a more compassionate embrace of our job as the ‘impossible profession’ and my place in it. How can I possibly be comfortable in the therapeutic position as long as I am ignoring, minimising or skating over that inherent impossibility?

This third, paradoxical position, ever torn between ‘one-person’ and ‘two-person’ paradigms, transcending and including both, never being able to simply exclude either, and reducible to neither, we could graphically represent like this:7

The sustainability of my practice, I contend, is proportional to the degree to which I can embrace and rest in that dynamic tension, inherent in that pervasive and ongoing paradigm clash. My practice is unsustainable to the extent that I am caught – maybe unwittingly – in resisting and fighting against its unpredictable paradoxical nature.

Having established the relevance of the therapist’s implicit relational stance in principle, as a crucial factor before and beyond theory and technique, in the summer issue I will look at some of the models available for distinguishing a diversity of specific relational stances.

© Michael Soth 2016

Michael Soth has been practising as a therapist, supervisor and trainer for the last 30 years. He describes his approach as broad-spectrum integrative, embodied, relational. www.integra-cpd.co.uk

Related articles

An impossible profession?

We need to become more embodied as therapists if we want to increase the sustainability of our practice, argues Michael Soth. Private Practice, Summer 2016

Risky business

It’s not only being empathic and attentive that’s exhausting for therapists, the bulk of the impact of the work is the result of being related to as a conflictual transferential object, argues Michael Soth. Private Practice, Autumn 2016

The dilemmas therapists don’t talk about

In the last of a four-part series, Michael Soth argues that by addressing some taboos and neglected areas of our discipline, therapy can work better for therapists, as well as clients. Private Practice, Spring 2017

References

1 Malan D. Individual psychotherapy and the science of psychodynamics. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd; 1979.

2 Gomez L. Humanistic or psychodynamic – what is the difference and do we have to make a choice ? Self & Society 2004; 31(6):5–19.

3 Bollas C. The shadow of the object: psychoanalysis of the unthought known. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1987.

4 Stern D. Relational freedom: emergent properties of the interpersonal field. New York, NY: Routledge; 2015.

5 Stark M. Modes of therapeutic action. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1999.

6 Soth M. The implicit relational stance underlying theory and technique. [Online.] http://www.integra-cpd.co.uk/cpd-resources/the-implicitrelational-stance-underlying-theory-and-technique-1995/ (accessed 15 February 2016).

7 Soth M. Integrating ‘medical model’ ‘one-person psychology’ and ‘anti-medical model’ ‘two-person psychology’ into a paradoxical third position. [Online.] http://www.integra-cpd.co.uk/cpd-resources/the-three-relational-revolutions-2007/ (accessed 15 February 2016).